Follow our journey to NZ’s largest fault

The Google Map may not work in all web browsers – if you have having trouble use Google Chrome.

We know more about the stars high above our heads, than about Earth just below our feet – Renaissance artist and naturalist Leonardo da Vinci (1452-1519).

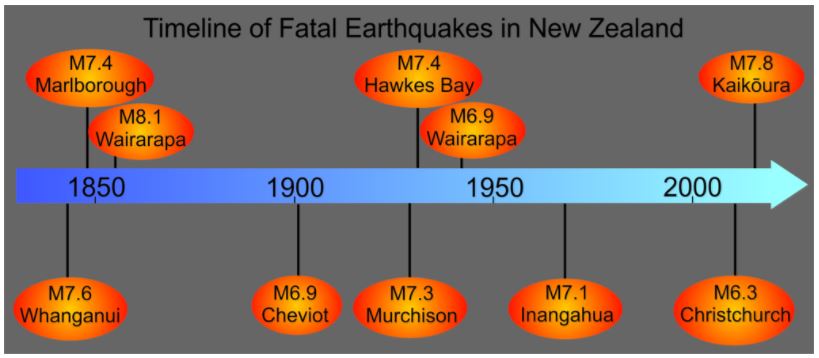

Being a New Zealander, I grew up feeling earthquakes – I often heard people call us ‘the shaky isles’. These rumbles and rattles were exciting, but they weren’t huge and didn’t cause much damage. This all changed with the first of several large earthquakes in the Christchurch area, September 2010. Many people lost their lives and the city is still damaged, seven years on. Just when we were all starting to feel more complacent again, a M 7.8 earthquake hit Kaikōura in late 2016, killing two and causing huge infrastructure damage and loss of livelihoods.

These events have showed us that there is still so much to learn about earthquakes.

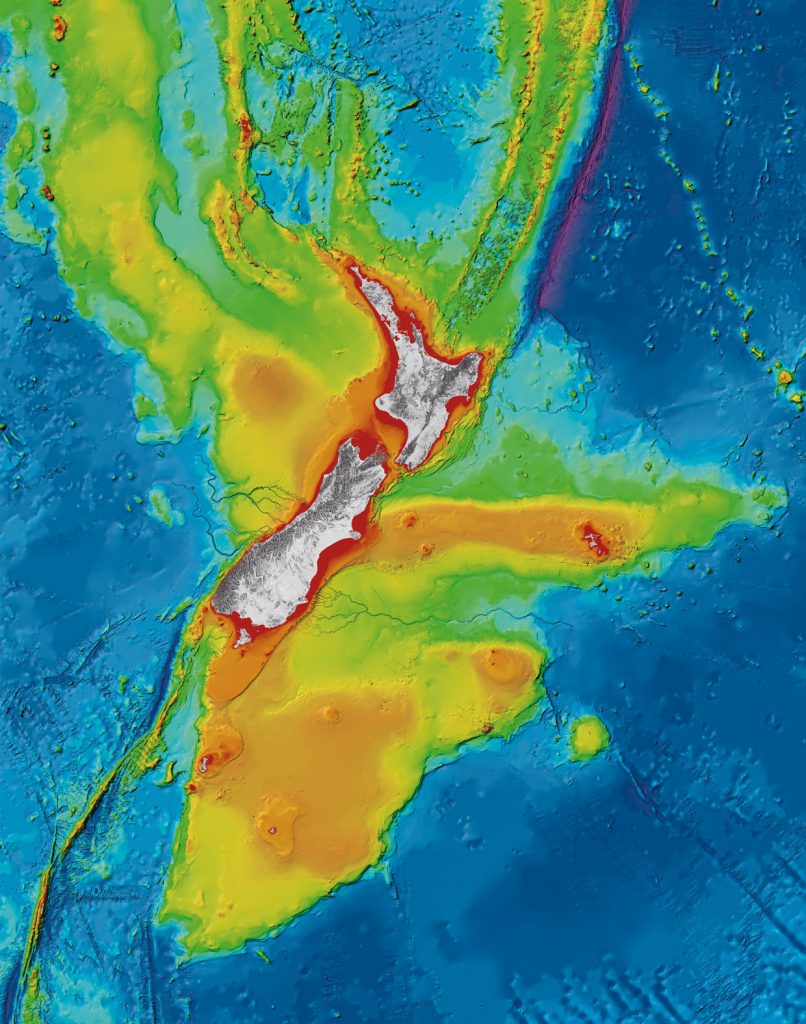

We don’t know when or how big they might be, nor where they will next hit. We also don’t know why some parts of large faults, like the Hikurangi Subduction Zone, are ‘locked’ and not moving, while other parts are slowly ‘creeping’ in slow slip events (also known as slow slip earthquakes, or silent earthquakes – because we do not feel them).

The 7.8M Kaikoura earthquake triggered slow slip earthquakes 500km north in the weeks after the earthquake, offshore of the southern Hawkes Bay region. It showed researchers for the first time that large-scale triggering of slow-slip events, extending over a very large region, could be due to distant earthquakes.

-

What are these slow slip events? What is happening deep in the fault when they happen?

-

Do they relieve the stress building up, or do they signal more activity to come?

Our journey to NZ’s largest fault – the Hikurangi Subduction Zone – aims to answer some of these important questions.

Along the way the Ship’s Log will cover our trials and tribulations. Follow our journey to hear about why we are going to study slow slip earthquakes, how we are doing that with deep ocean drilling equipment, and see if we can successfully install two deep sea observatories, a first in NZ and a precursor to earthquake early warning systems.

Follow us

Follow our journey on the interactive map above, and you can ask us a question anytime on twitter @TheJR by using #askJR and #AskAScientist. You can also find us on Facebook and Instagram, and on our YouTube channel.

If you’d like your group or class to talk to us in person you can sign up for a live broadcast to connect with the JR scientists here.