Core Science #1 – What is coring and what does it tell us?

What is coring exactly?

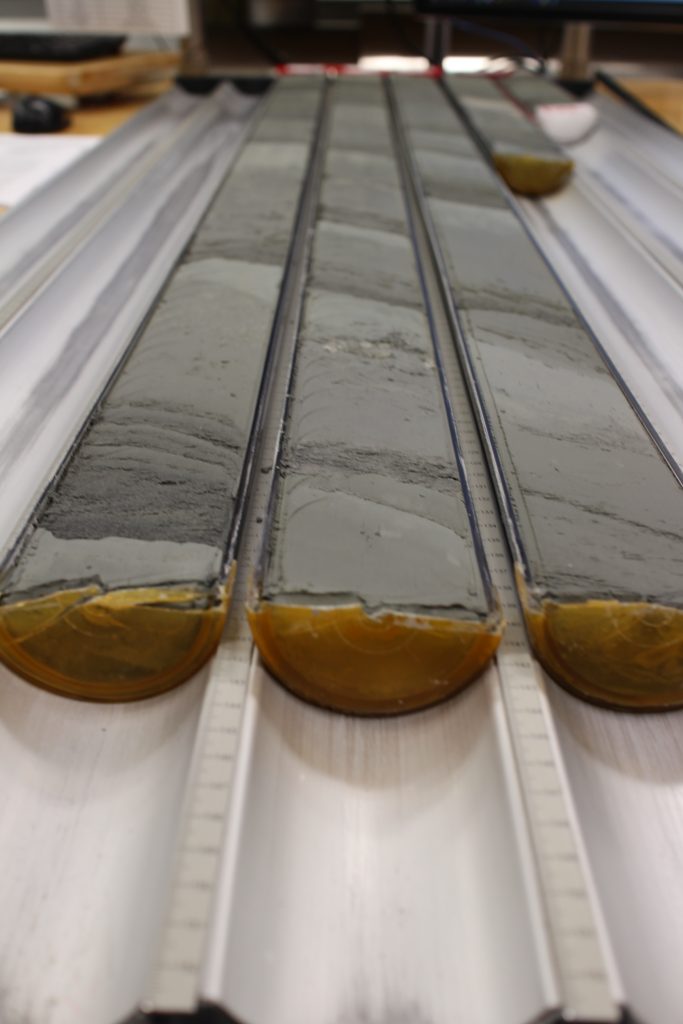

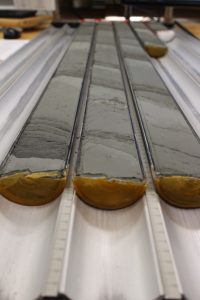

What we call a ‘core’ is simply a long tube of sediment (or when it’s harder, rock) captured by the drill bit as it moves deeper beneath the seafloor.

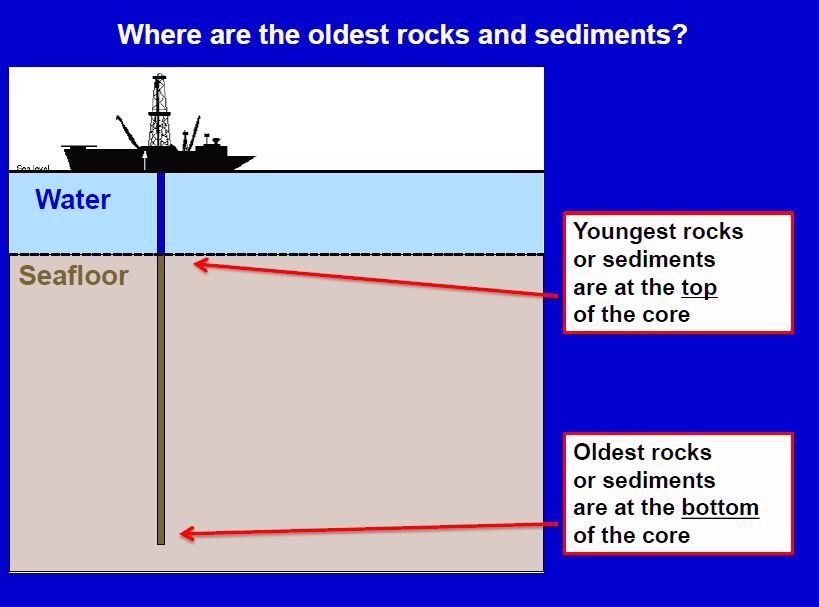

Here’s a simple diagram to visualise this. The younger sediment (such as mud or sand) is at the top closest to the seafloor, as these were laid down more recently. The deeper you go the older the sediments get.

Coring the Hikurangi Subduction Zone

One of the key objectives of Expedition #375 to the Hikurangi Subduction Zone is to core at different sites above the megathrust fault to understand the physical and chemical properties of the rocks and sediment.

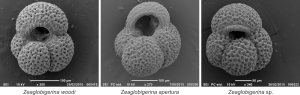

We’re also looking carefully at markers hidden inside the core samples that tell us its age and the past environment it was created in. One type of age marker are micro fossils. Another technique is to look at magnetic field reversals ‘imprinted’ like a barcode in each core. The Earth’s magnetic field has flipped back and forth over millennia, and we have a record of these reversals in time that we can compare our cores to.

Coring CSI

These techniques all tell us the age of each layer of sediment in the core, and the layers progressively get older the deeper we drill. Sometimes we might find a younger layer mixed in with an older one, and that could indicate a fault has deformed and ‘curved’ in a younger layer into an older layer. Other times we might get older sediments from the land flowing out into younger ones. Geologists get pretty excited when they find that, but it can take time to unravel. It’s a bit like forensics or CSI really – looking at clues and deducing what has happened to each core sample, to build up a picture of its past.

Some layers are laid down slowly as tiny particles of sand, mud, algae and sea life fall to the seafloor. Others are laid down quickly and are what is called a ‘turbidite’ – this is sediment that has flowed in a current from the land (from rivers and in storm events) or across the seafloor suddenly in earthquakes.

A sediment highway off shore of New Zealand

Research just published has shown that sediment from the (Mw) 7.8 November 2016 Kaikōura earthquake (New Zealand) was pushed quickly in a turbidite current all the way north >680km into the Hikurangi Trough. The turbidite current travelled along deep channels on the seafloor to where the JOIDES Resolution is now. We might find further evidence of this at our sites on #EXP375.

A giant conveyer belt

You can think of this whole sedimentary process as a giant conveyer belt happening over a massive timescale of millions of years: sediments in the ocean basin off the East Coast of New Zealand are being uplifted, folded and pushed onto the land in earthquakes and with sea level changes. They then weather and erode to flow back down into the sea again.

Before and after – life of a Core

Watch this short clip to see how we collect Cores from drilling, and what happens to them after the scientists have analysed and taken their samples.