Hearing the creaks and groans of the Hikurangi Subduction Zone

What is special about the northern Hikurangi Subduction Zone?

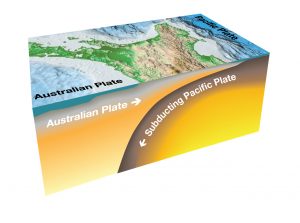

Subduction Zones are where two tectonic plates collide, and one of the plates (usually the heavier one) dives down beneath the other plate and sinks back down to the mantle. During this process, stresses and pressure can build-up along the plate boundary over time and is episodically released when the two plates slip past each-other. At subduction zones, this cycle repeats over a period of years to decades. In some cases, the slip is sudden, and leads to some of world’s largest and most damaging earthquakes and tsunami. In other cases, the slip occurs more slowly, in slow slip events (or SSEs), which relieve the built-up stress over several days or weeks.

This is what is happening at the Hikurangi subduction zone, where the Pacific Plate dives or “subducts” beneath the Australian Plate.

The northern part of the Hikurangi Subduction Zone experiences the world’s shallowest slow slip events. Slow slip earthquakes (also called ‘silent’ or ‘creeping’ earthquakes) release energy, but unlike regular earthquakes, this happens so slowly that it is not felt on land. This type of earthquake was discovered about fifteen years ago by scientists using sensitive GPS equipment. In northern Hikurangi they recur every one to two years over periods of two to three weeks, at depths of only 2–15 km below the seafloor.

Because these enigmatic events are happening at such a shallow depth, the northern Hikurangi system is an ideal place for the JOIDES Resolution to install sub-seafloor observatories.

The puzzle we are putting together on the JOIDES Resolution will help earthquake scientists all around the world understand why slow slip events happen on subduction zones, and what they mean for earthquake and tsunami hazard.

The observatory mission at Site U1518

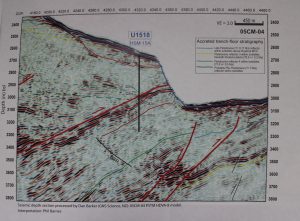

We are currently at our first drilling site, called Site U1518.

We have cored to 495 m below the seafloor and had a first look at the sediments surrounding one of the main Hikurangi plate boundary faults, and its physical and chemical properties.

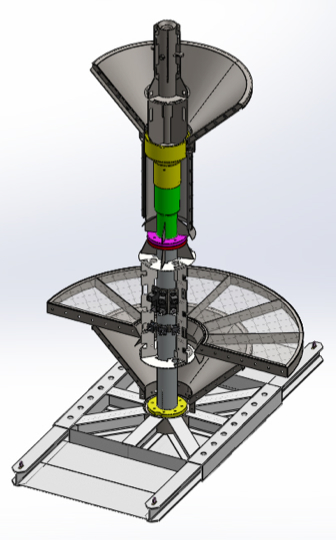

Now we are lowering an observatory into the borehole to monitor the chemical, physical, and thermal changes at the subduction zone between and during many slow slip events over the next decade..

Te Matakite – to see into the future

This first observatory is the most complex on Expedition #375, and the first of its kind in New Zealand. Before the voyage, GNS Science (in New Zealand) ran a competition between schools on the East Coast to name it for us. The winning entry came from Gisborne Boys’ High school student Matthew Proffit, who gave it the Māori name ‘Te Matakite’ which means ‘to see into the future’.

It will be our ‘eyes and ears’ in this area of slow slip events as we record the creaks and groans of the Hikurangi Subduction Zone.

You can watch Matthew Proffit’s video here: