Impressions from the microscopic worlds of Brothers Volcano

Many of the scientists aboard Expedition 376 have been looking at tiny features in extremely thin slices of rock. They’ve been in search of certain minerals, telltale indicators for particular processes, or perhaps microscopic bubbles that have entombed a special fluid or gas. Sometimes, even a single grain can reveal something spectacular!

I was eager to have a look at some of the thin sections made from the core we’ve retrieved. I’m not trained to identify minerals, nor to spot fluid inclusions.

So I decided to (momentarily) reject scientific instinct, and seek impressions instead: I’ve certainly spent enough days at sea now to “see things”.

I’ve used reflective light because art is a reflective process *coughs*

Below my impressions are reported.

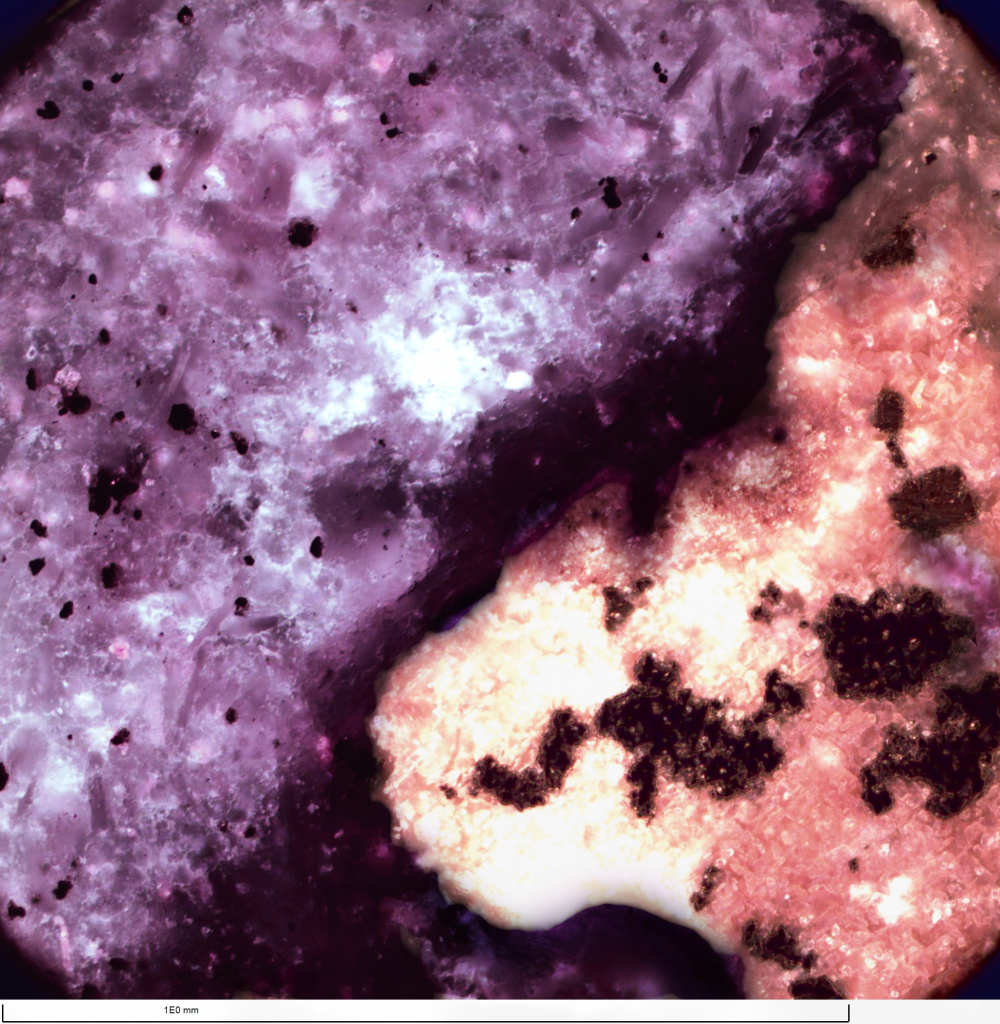

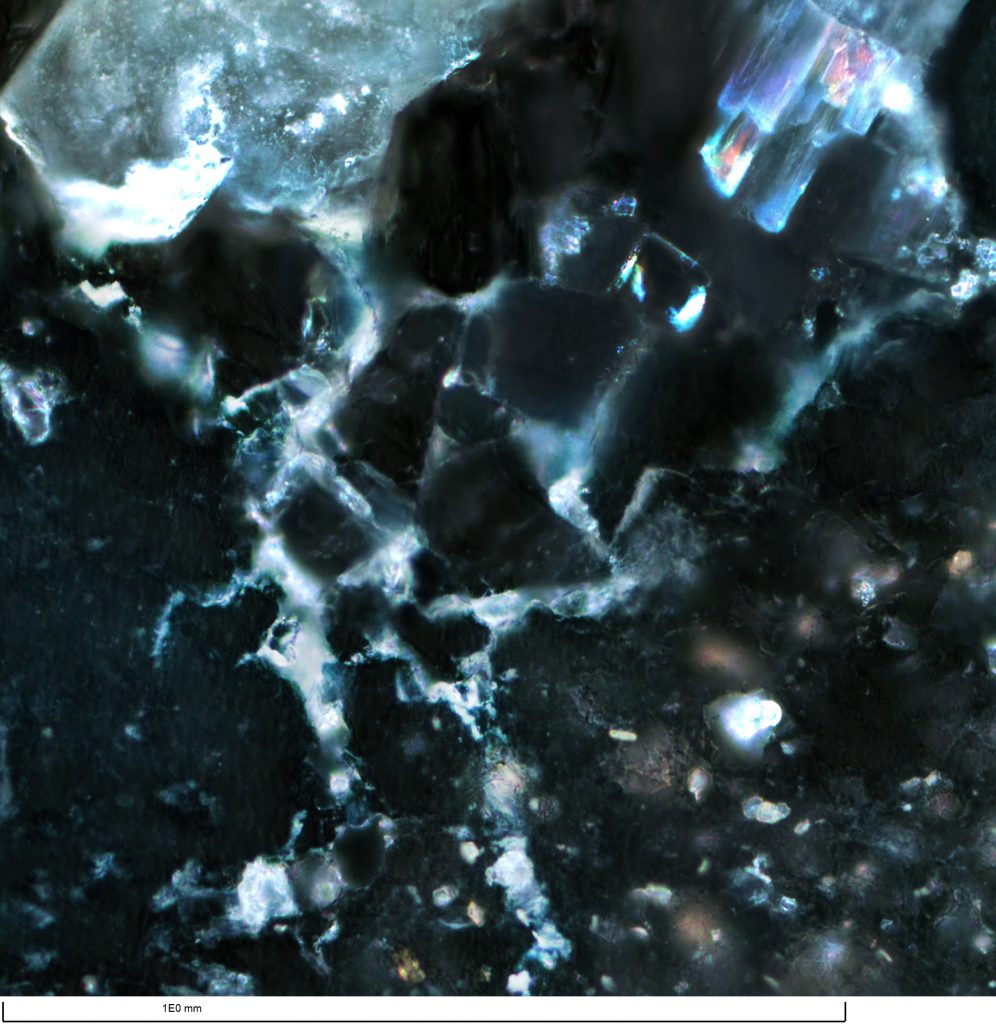

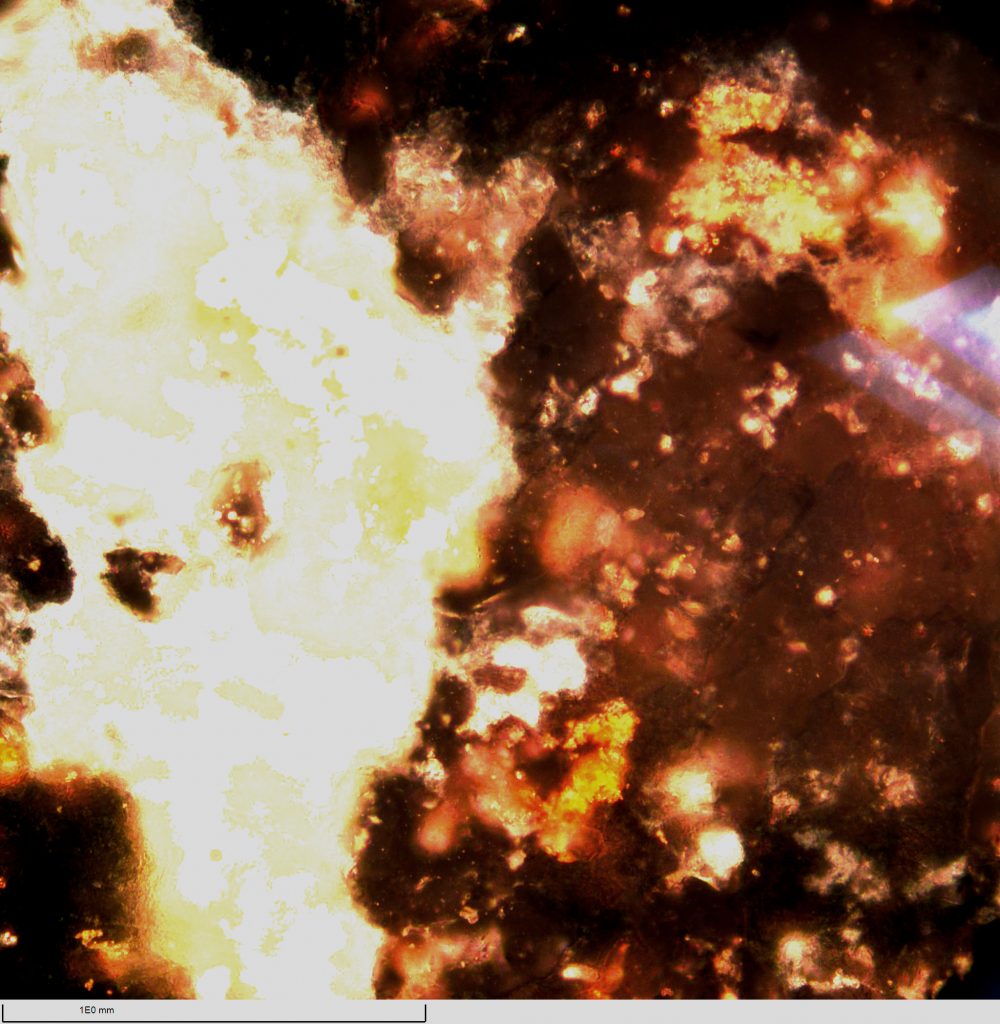

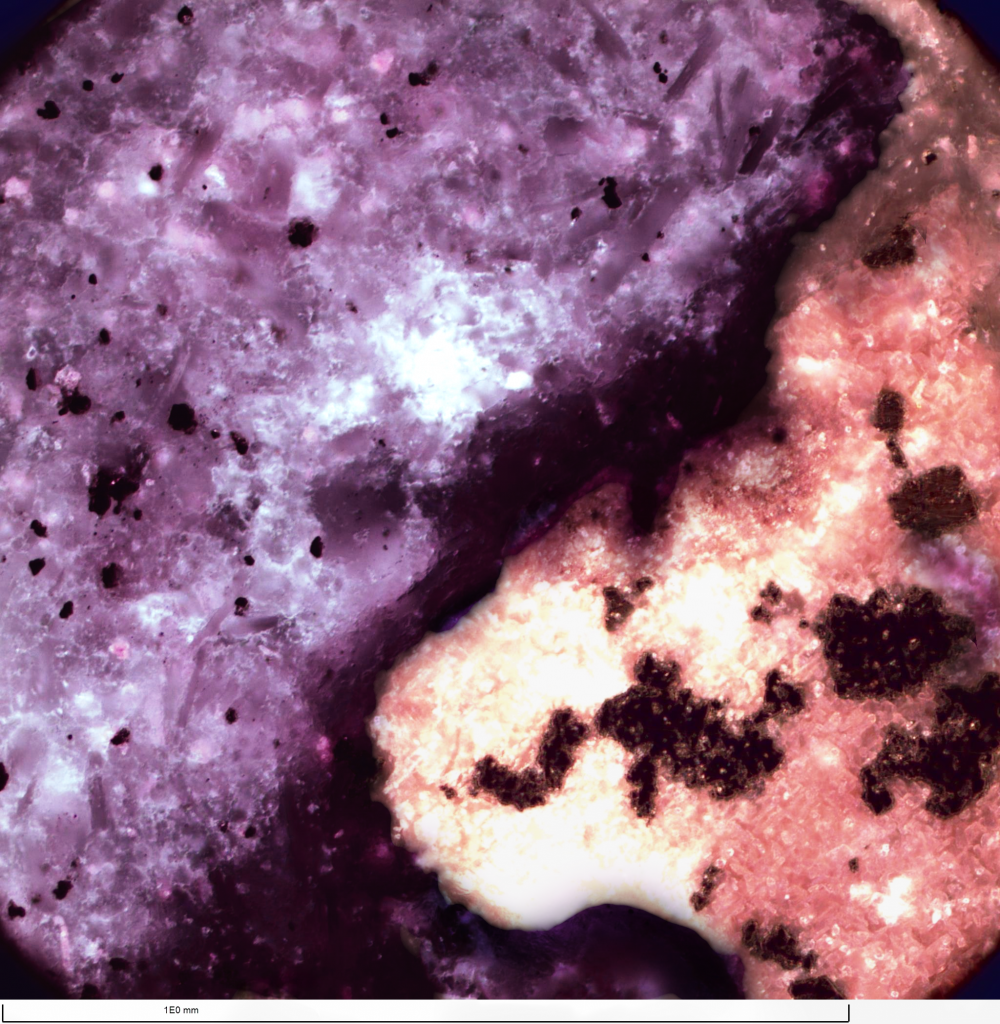

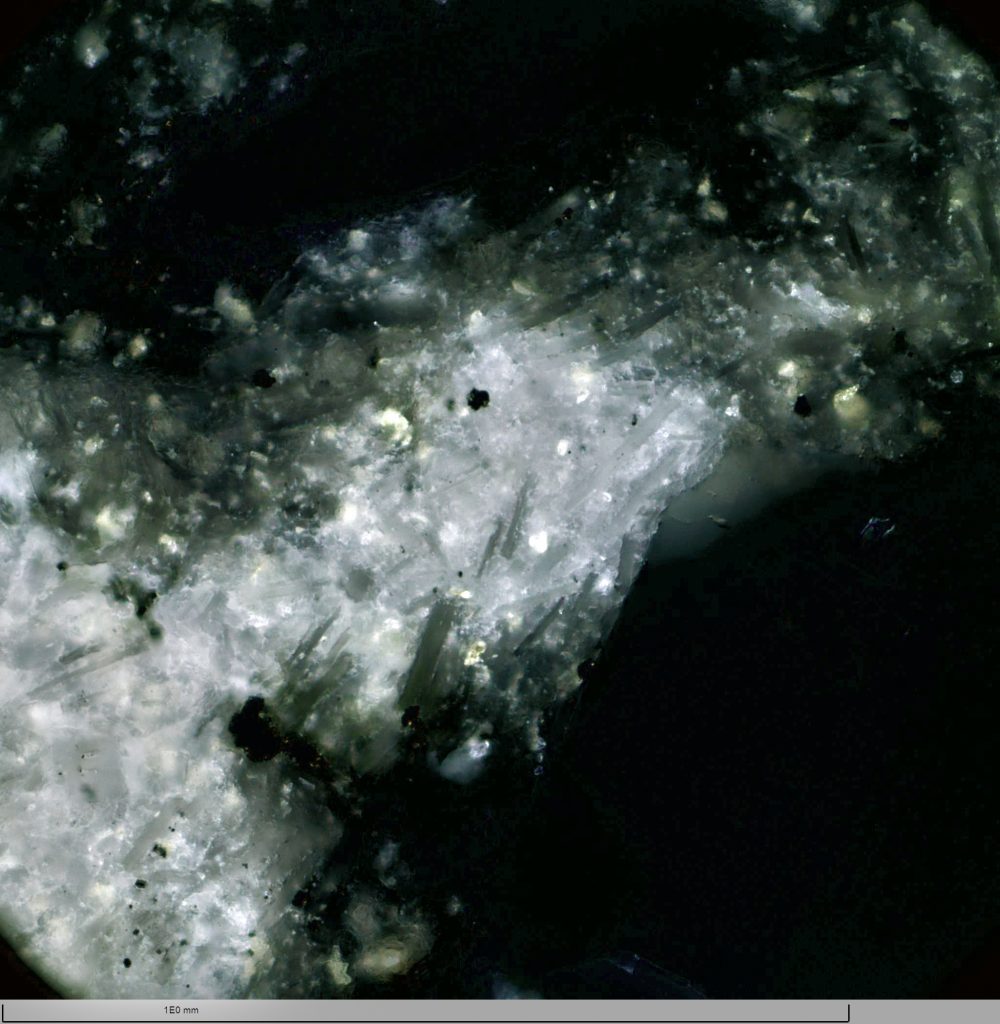

The following images are micrographs of thin sections made from the rock of Brothers volcano.

1. There is water at the bottom of the ocean

It seems that there is a lot of water down there (Fig. 1). This should not come as a surprise because this volcano is at the bottom of the ocean (which is largely water). What is surprising is that this formation resembles a waterfall. This would be consistent with my impression (1) as water generally accompanies waterfalls (with some exceptions at alleged “waterfall” sites in Australia). It seems that water is trickling down into the rocks beneath the seafloor…

2. There is molten rock down at Brothers volcano

It looks like there is molten rock deep within the volcano too. Again, as this is an active volcano, this is probably not surprising.

3. The water is heated by the molten rock

This impression follows from (1) and (2) but I think this image says it all! The water trickles down close to the molten rock and gets super hot.

4. Water dissolving and water removing

Leaching is the word that comes to mind. Minerals are being dissolved, and carried away by the hot torrent of fluid flowing through the rock far below. This is a very important process in the transport, concentration and alteration of volcanic rocks and is almost certainly not what I’ve captured in this image.

5. The hot fluid finds its way to the surface, and gushes out of the seafloor, sometimes forming smoker chimneys.

What goes down, must come up (in specific situations involving convecting fluids). I didn’t actually take this image, and the trained eye may notice this is not actually a micrograph. This smoker chimney is nearly 20m high – that’s high enough that the lights of the ROV (Quest 4000) aren’t able to reach the seafloor below! It’s tricky to photograph big things in the deep!

Even with cameras, down at the volcano, we can only see one small scene at a time. But small scenes can be pieced together to build a story on a grander scale.

Mā te wā