Hikurangi – the origins of this sacred name

Hikurangi Te Toka Tapu

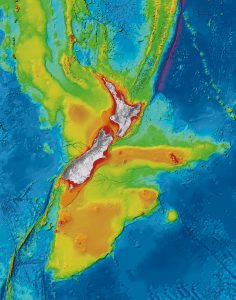

Crew on the JOIDES Resolution found themselves looking due west at a majestic Mt Hikurangi on Friday, as we sat directly over the Hikurangi Subduction Zone. It seemed timely to reflect on the special name given to this plate boundary.

Hikurangi, the sacred maunga (mountain) of Ngāti Porou, holds a special place within the hearts, minds and souls of the indigenous people of New Zealand, the Māori. It towers over the coast and faces the plate boundary. The mountain is a cultural icon venerated through story, song and speech, and Hikurangi also symbolically represents “home” for the 70,000 plus Ngāti Porou tribal members (tangata whenua) who live on the East Coast and in other parts of the world.

Standing at 1754 metres, Hikurangi is the highest non-volcanic mountain in the North Island. It is 130km north of Gisborne, on the east coast of New Zealand. The region is known as “Tairāwhiti” – the light shines on the water – and is recognised as the first point on the New Zealand mainland to greet the morning sun. This is quite neat for those of us on the ‘night shift’ (working midnight to noon) because we’ll get to see about 55 sunrises!

The story of Hikurangi – Māui and Nukutaimemeha

Maui, a legendary Ngāti Porou ancestor, accomplished many heroic deeds. It is often said that the North Island is Māui’s fish and the South Island his canoe, but the East Coast tribe, Ngāti Porou, believe the canoe ended up somewhere else. They say that the first part of the fish to emerge from the water was their sacred mountain, Hikurangi. Māui’s canoe, Nukutaimemeha, became stranded on it, and is still there in petrified form (Te Ara website, https://teara.govt.nz/en/whenua-how-the-land-was-shaped).

To celebrate the sacredness of Hikurangi, nine whakairo (carved art works) rest on the mountain. The carvings tell the story of Māui fishing up the North Island, and how his petrified canoe came to lie in a lake on the mountain. They are set in a compass shape and also represent the four winds, to honour Ngāti Porou man Mohi Turei, who gave the compass points Māori names last century.

Our work here

Ngāti Porou oral tradition recognises the land on the east coast has come from the sea, and the people here are intimately connected and aware of the dynamic nature of the East Coast.

The scientists on board come from all around the world, but are cognizant of the importance of Hikurangi Subduction Zone research for the people of the East Coast, and the rest of New Zealand. Information that the core samples and sub-seafloor observatories will give us over the next 2-5 years will be used to improve our seismic understanding of this plate boundary, and therefore our earthquake and tsunami preparedness. Better preparedness means more lives saved if the Hikurangi Subduction Zone was to experience a large earthquake in our lifetime.