It Takes a Team to Make Science Work

It Takes a Team to Make Science Work

One hundred and seventeen individuals boarded the veteran JOIDES (JR) research vessel in Reykjavík, Iceland last week. They arrived from all over the world for the chance to join the dig into the sedimentary pages of glacial history buried off the coast of Northwest Greenland. A wide array of earth scientists, including sedimentologists, micropaleontologists, paleomagnetists, and more, along with technicians, the ship’s crew, drillers, cooks, stewards, and outreach officers, have all gathered here with a common purpose: to support the scientific objectives of the expedition. Collectively we represent at least twenty-one countries.

IODP Expedition 400’s reliance on teamwork was exemplified from the get-go, as the two tugboats, Magni and Haki pitched in to guide the ship out of Skarfabakki Harbour. At 143 meters (470 feet) in length, the JOIDES is big for a research vessel but mid-sized to small compared to a number of other modern ships, including most cruise ships, ocean-going container and bulk vessels, large modern naval destroyers, as well as true behemoths like the U.S. Navy’s 333 meter (1,092-foot ) long USS Gerald Ford aircraft carrier.

(Beth Doyle, IODP)

Why would the JR need assistance from smaller boats?

In the open ocean, vessels of JR’s size can sail at speeds that enable the ship’s rudders to effectively control its movement and utilize the necessary distance for maneuvering. In confined and shallow waterways like harbors, the tugboats are especially helpful to bigger ships that are leaving or arriving at a berth. They are highly maneuverable vessels with powerful engines. Working closely with the ship’s crew and harbor pilots, tugboat operators help to pull the vessel away from the dock, while the vessel speed is still close to zero. Tugboats also counteract the effects of wind, current, and tide, reducing the risk of collision or damage to the ship or the harbor infrastructure.

Heading north, but first south.

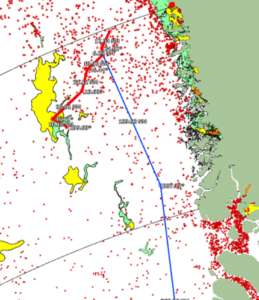

For most of this expedition (the JOIDES Resolution has completed ~200) the JR will be drilling in sites along Greenland’s continental shelf and slope in Melville Bay. This body of water opens into the larger Baffin Bay. To get there, the ship initially heads southward from Iceland to Greenland’s southern tip, and then steers northward along the west coast of Greenland. It’s a journey of nearly 1,800 nautical miles, with the ship’s GPS tracker and fixed points along the route helping the crew to stay on course. The latitude, longitude, and bearing are constantly monitored. We’re currently a little north of 60 degrees latitude, a number we won’t see again for two months as we head as far north as 74 degrees, well above the Arctic Circle at approximately 66.5 degrees.

Greenland in sight!

After only a few days of sailing, word spread that a distant shore was just in sight. The crew rushed up to the starboard bridge to capture a glimpse, the first time for most, of the land linked to their expedition. Even in the mist, Greenland’s coastal sculpted peaks and alpine glaciers pop out on the horizon.

Pitch, roll, heave and more

Combined with the ship tracker, the daily weather report dishes up a number lover’s feast. This report provides essential data on wave heights, wind conditions, and other variables. The waves affect the ship’s stability and motion, described with words like “pitch,” “roll,” “yaw,” “surge,” “sway,” and the occasionally all-too accurate “heave.” The ship crew must navigate through these conditions and adapt to changing weather patterns. The captain’s report tells the rest of the crew what to expect. Here’s a typical one:

“Winds should come down later today / tonight. Early next week will be windy again. A little uncertain how windy, might be little more than on the forecast.”

And ice…

Soon enough, ice in abundance may enter the picture, and so, crucial to this expedition are the two ice navigators on board. From the bridge they monitor potentially hazardous ice movement, particularly icebergs. Ice navigators apply their extensive knowledge of ice physics, polar geography, navigation techniques, and maritime regulations in icy waters. The sighting of an iceberg for many on board is another “first,” so news spread fast when one was caught in view late in the night.

Our prospects for a safe journey and ready access to the drill sites are best summed up by Ice Navigator, Victor Gronmyer,

“The expedition organizers accounted for both the sea ice and pack ice to retreat from the area where we’re headed. It turns out, the timing is perfect,” Gronmyer said. “They could not have planned it better. “

Having successfully navigated around the southern tip of Greenland, we now set our course northward aiming to reach the first proposed drilling site in the coming midweek. En route, we eagerly anticipate the collection of valuable data and more stunning vistas. Keep watch for further updates!

Very interesting!

Glad you liked!!