Ka mua, ka muri – Walking backwards into the future

Looking to the past to inform the future – historical events on the Hikurangi subduction zone

New Zealand’s geological setting is complex and the quest to understand future earthquakes — where, when and with what magnitude they might occur — is one that has been testing seismologists and civil defence authorities for many years.

‘Megathrust’ quakes in subduction zones have been the cause of major disasters, including the 2004 Boxing Day tsunami that killed 230,000 people around the Indian Ocean, and the 2011 Tohuku tsunami in Japan that left nearly 16,000 people dead.

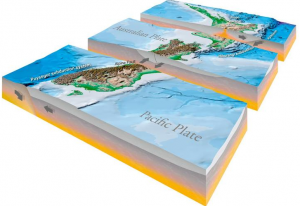

At the Hikurangi subduction zone in the North Island of New Zealand, the Pacific plate subducts beneath the Australian plate creating the conditions in which large, so-called ‘megathrust’ earthquakes and tsunami could be generated. While geoscientists have unearthed evidence showing that the East Coast of New Zealand had been hit by large tsunami and megathrust earthquakes in the past, much about the size and frequency of those events remains unclear.

The gaps between major earthquakes can be hundreds or even thousands of years and so any information that helps us to piece together a pattern of past seismic events is helpful.

Earthquake History – how oral history sheds light on past events

Modern seismology is a relatively young science, and seismometers, as we know them today, have been around only since the beginning of the twentieth century.

Because the cycle of continual breakup and convergence (which is the cause of the vast majority of the planet’s large earthquakes) takes place over millions of years it is hard to find records of past events in an effort to identify patterns of future earthquake behaviour or seismic hazard.

In New Zealand, iwi (Māori tribes) have an oral history of earthquakes and tsunami going back to about 1300 A.D. Archaeological studies have shown that during the mid-15th century, many Māori moved their settlements from low-lying coastal sites to hilltops and inland sites. A number of the abandoned coastal settlements show clear evidence of tsunami inundation.

Because NZ was only relatively recently settled (sometime between 1250 and 1300 A.D. the first waves of canoe voyagers arrived in NZ) the human record does not go back much longer than hundreds of years. And this is a problem when the time between major earthquakes on some stretches of the plate boundary could be much longer.

Identifying Prehistoric Earthquakes

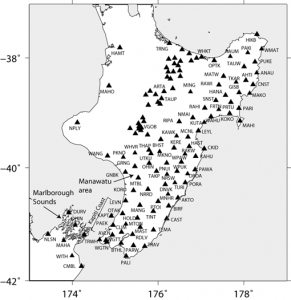

Researchers at GNS Science in New Zealand have been focusing on an area of the Hikurangi subduction boundary beneath the southern North Island. Global Positioning System measurements of this area suggest that the fault is currently locked-up and is building up stress that will eventually be relieved in a future large megathrust earthquake.

A ‘megathrust’ earthquake is one that is capable of generating Magnitude 8 or 9 earthquakes when two plates converge together at a subduction zone.

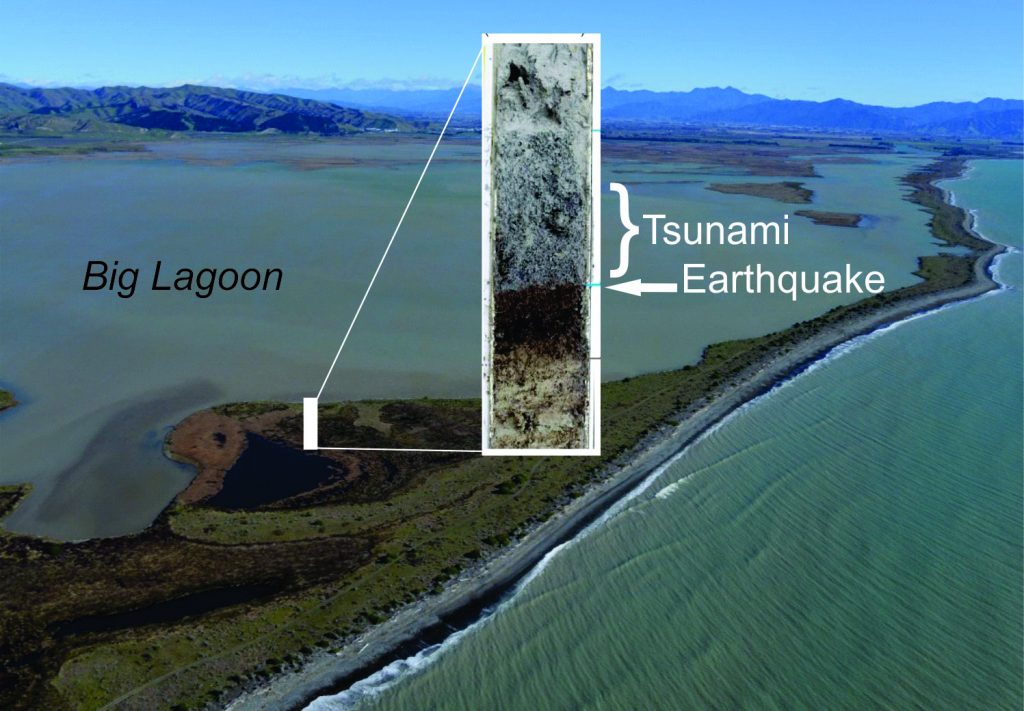

Microfossil evidence in cores taken from Big Lagoon in the northern part of the South Island identifies two episodes of land subsidence that are likely due to large earthquake ruptures on the southern Hikurangi subduction zone. The earliest of these occurred between 880 and 800 years ago and the later one between 520 and 470 years ago.

The results are significant because we now know the Hikurangi subduction zone, at least the southern portion of it, can rupture in large earthquakes, probably greater than Magnitude 8 events. There is also some indication the 2016 M 7.8 Kaikoura earthquake involved some degree of rupture of the Hikurangi subduction zone beneath the Marlborough region, suggesting that the subduction zone is capable of generating earthquakes well into the northern South Island.

Ancient Quakes: Lessons Learned

It is only by looking to our past that we can make sense of our future – Ka Mua, Ka Muri.

The Expedition 375 team are piecing together what they can out at sea in the Hikurangi subduction zone. They are also working with paleo-seismologists and local iwi back on land to fill in the past by understanding when great earthquakes and tsunamis last occurred on the East Coast. To learn more about this work visit: New Zealand’s largest fault.

And you can watch a video describing the work below: