Microfossils Making Macro Impacts

The ocean is teaming with life. Most of this life is in the form of microscopic organisms floating around and doing their thing. One of the interesting things about these microscopic communities is that they make up the base for the entire marine food web. Without these tiny creatures, there would not be the scores of others organisms that call the ocean home. They are interesting as well because they are great at recording history. They do not write it down like people, but they carry the record of the ocean’s history in their minute calcareous (calcium-based) shells. When these microorganisms die, they slowly sink to the bottom of the ocean where they become incorporated in the sediment there. Layer after layer, they accumulate and leave behind a record of the ocean’s history.

Because some of these organisms are widely spread, they can indicate how the water in the global ocean has changed and the time at which the changes have happened. The chemical composition of their shells are indicators of water chemistry, such a pH, temperature, and CO2 levels and their evolutionary changes over millions of years can show the timing of their deposition. The use of these fossils to determine the relative age of sediments is called biostratigraphy.

Paleoecologists can use biostratigraphy to recreate time lines of climate change. The elements in microfossil shells are used to recreate past environments in the ocean. Isotopes of Oxygen and Boron can indicate what the temperature and the pH of the water (respectively) was when the organism was alive. The number of organisms also changes through time so by looking at the number of individuals present, a paleoecologist can determine a general age of the sediment. All of this information together can be used to infer how the climate has changed over millions of years.

Who are these tiny fossil creatures on board the JR?

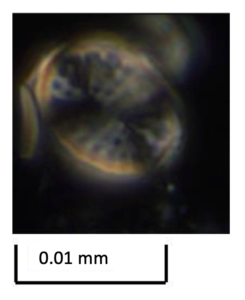

The foraminifera called Globigerina bulloides are small, single-celled protists that create popcorn shaped calcareous shells. When alive, these shells have

tiny spines and the organism uses pseudopods (they look like thin filaments emanating from the shell) to trap and digest their prey. Coccolithus pelagicus are also being identified and recorded. These single-celled organisms, called coccolithophores, create beautiful calcite plates which form an outer spherical shell – like tiny rolled armadillos of the sea! In fossil form, all that is left is the scales as the organism inside the sphere has died. In life they are photosynthetic (making food from the sun’s energy like a plant) and when they are plentiful can be seen from space in blooms.

The paleontologists aboard the JR will be looking at what different species are present and how the percentage of these species changes throughout the cores that are brought up. This can indicate the age of the samples and also which areas of the samples should be analyzed further for chemical evidence of ancient climate.

This reminds of when I went out on a research boat out of Woods Hole . We too were looking at microbiology.. For years I kept the core samples in the freezer. 1997 the boat was the Oceanus

I think in my classroom, I would put this in a climate unit to develop microscope skills using protists. Then, tie in ocean acidification (pH) and the calcareous shells of foraminifera. I am curious about the magnification in the images and I didn’t know that some were photosynthetic.

Thanks for the comment Camille! The magnification along with the images is correct. The Coccoliths are very tiny (they are pieces of an organism), while the foraminifera are somewhat larger. The ones in the image can be seen with the naked eye. The coccolithophores are photosynthetic while the foraminifera in this photo are heterotrophic.