Q&A with Co-Chief Mike Weber

As we enter the last week of our cruise, and finish up at our last drill site, I sat down with co-chief scientist Mike Weber to talk about these Iceberg Alley drill sites which made up the bulk of our expedition, and what he’s looking forward to scientifically after the expedition is over.

Why were these sites chosen, and what were you hoping to get out of them?

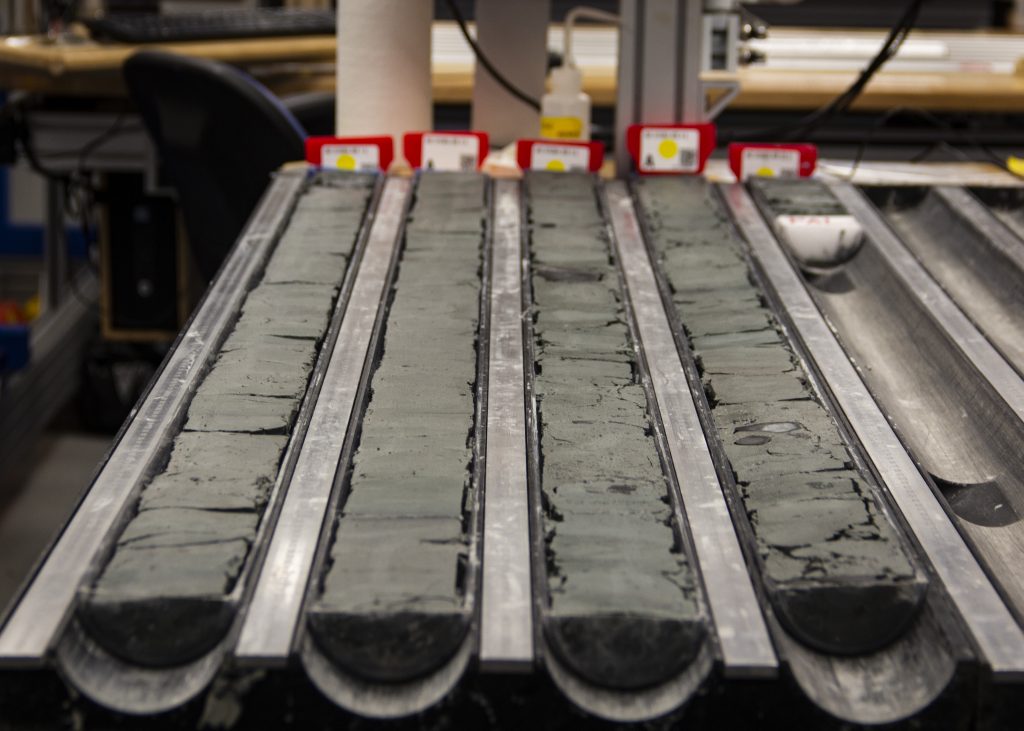

The general area was chosen because we realized – from previous shorter cores – that we might find rocks left behind by icebergs – or ice-rafted debris (IRD) – in this sediment. We chose one site in the South (Dove Basin) and one in the North (Pirie Basin) to take into account the differences in sea ice, water temperatures, and wind strength relative to the continent of Antarctica. We were hoping to get long and continuous records to reconstruct Earth’s climate during periods of past change that tell us about times of higher temperatures and higher sea levels worldwide – a likely scenario that we are facing in our immediate future!

Had this area been drilled before?

We were here a decade ago and sampled two short cores in this area. There were no deep drillings in the area before that, and the short cores only gave us a glimpse into the last ice age. But that ice age was 20,000 years ago, and we want to look millions of years ago in Earth’s climate.

What is most exciting about what we’ve found so far?

The number of climate cycles that we’ve captured is way beyond what I could have dreamed. The change from a warm planet to a cold planet, which makes up a climate cycle, takes about a hundred thousand years. We didn’t even get a full one in the short cores that we collected years ago. So I saw the potential, but I wasn’t sure. I thought, “If I get eight of these cycles, I would be overjoyed.” And now we have a climate record of 4 million years. It’s far beyond anything I was dreaming about.

Also, in geology, the most important thing is to get your time right. If you don’t know exactly how old the sediment that you’re look at is, your discoveries can always have holes poked in them. It’s like if you found an artifact, and you didn’t know how old it was, how can you know anything about the history?

But here, we know what the age of the warm and cold times are by three independent tests, so we’re robust as a rock, whatever we interpret. So if you ask me what was the most exciting – all of it!

Was there anything unexpected?

What was unexpected was that in the older part of the record, the Antarctic glaciers were apparently almost where we are now. We’re still thinking about that one.

What projects are these cores going to contribute to?

Data from this expedition will help to answer lots of questions we have about Antarctica and the ocean that surrounds it. How far did sea ice reach during ice ages? Where did the icebergs that dropped the rocks we find in our cores actually come from – where on the continent exactly? We can use our cores to look at how nutrients are moved around by the ocean, and track those ocean currents in the past – including the world’s largest, the Antarctic Circumpolar Current. We can even look to see how the winds in the Southern Hemisphere changed over time.

How will these cores affect our understanding of Antarctica’s future?

The past is the key to the future. People who build computer models of changes in Antarctica and the Earth under human-caused climate change need to know how those places changed in the past under similar circumstances of higher greenhouse gas concentrations, higher temperatures, and elevated sea levels. There are a lot of unknowns about why Antarctica melts and how it melts. With the first continuous record that goes back to critical timescales, we might be able to solve a few of these mysteries.