School of Rock 2019: Day 3 – Wednesday, September 11, 2019

Day 3: Wednesday morning!

by Sara Beck

It was another beautiful morning in San Diego!

We arrived on campus this morning to find that Dick had selected and arranged an amazing collection of rock samples for our first activity of the day: a lab examining sedimentary rocks and sedimentary structures. After a quick “Sedimentary Rocks 101” crash course, we were ready to begin!

We all excitedly pounced on rock samples from all four categories of sedimentary rock, which all form at or near Earth’s surface in one of the following ways:

- Clastic sedimentary rocks – cementing loose clasts (fragments) of preexisting rock. Examples we viewed: claystone, siltstone, sandstone, conglomerate, breccia.

- Biochemical (or biogenic) sedimentary rocks – cementing together loose shells and shell fragments. Examples we viewed: fossiliferous limestone, coquina.

- Organic sedimentary rocks – accumulation of carbon-rich organic matter from living organisms. Example we viewed: Miocene-aged oil sand from Santa Cruz.

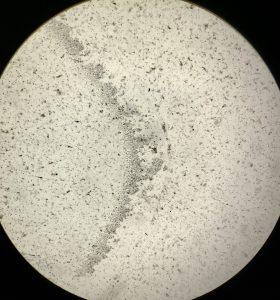

- Chemical sedimentary rocks – precipitation of minerals dissolved in water, including evaporite minerals like halite (salt). AMAZING example that we were lucky to get to view: 300 million year old salt from Colorado with fluid inclusions! See image below of the thin section under petrographic microscope, magnified 10x; the bubbles are the darker gray portions forming the crescent shape.

Why was this halite (salt) sample so interesting? These are little bubbles of ancient sea water, preserved inside the salt crystals, which could contain viable (but “hibernating”) bacteria – 300 million year old bacteria. To help put this time frame into perspective, this bacteria would have inhabited the oceans over 50 million years before any dinosaurs roamed the planet!

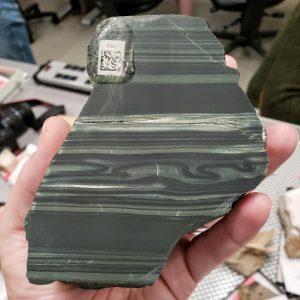

Our objective in examining these samples of unlithified (unconsolidated/loose) sediments, sedimentary rocks, and thin sections was to interpret the depositional environment and try to glean any additional information possible regarding general chemistry and oxidation states. Clues included grain size and texture, color, and sedimentary structures like laminations, small-scale cross bedding, and rain drop impressions. Pictured below: early Paleoproterozoic laminated mudstone from the Gowganda Formation in Ontario, Canada.

Following that wonderful experience was a great talk by Lisa on how science works and some of the excellent teaching resources available online through the University of California’s Museum of Paleontology at Berkeley. Most of us are science teachers and tend to teach the standard, oversimplified 5-step “Scientific Method” lesson, but know that the real scientific process is much more complex and non-linear. This can be difficult to convey to students without overly focusing on only the conclusions of scientific discoveries, when the process of science is just as important to understand and appreciate. The “How Science Works” website allows students to get a better impression of how science really works and even allows them to chart their own progress through a scientific question with an interactive journaling tool. Check it out for yourself at www.understandingscience.org!

Day 3: Wednesday afternoon!

by Heather McCandless

After our time in the lab, we picked up some sandwiches from the Cheese Shop close by and headed to Mission Trails Regional Park to look at another example of an outcrop and practice reading and interpreting geological features.

When we got to Mission Trails and started to divide up the sandwiches, we were pleasantly surprised to find everyone’s name kindly written on the outside, so we didn’t have to open each one up to figure out who it belonged to. Ironically, once everyone had their sandwiches and started to unwrap them, lots of exclamations came as people realized the sandwich in front of them wasn’t the one they had ordered! Thus began a flurry of trades and search expeditions as everyone tried to hunt down the sandwich that actually belonged to them. Thankfully, once everyone had their proper sandwich, we all had a delicious lunch and full bellies.

After lunch, we met up with Tom Demere and Ashley Poust from the Natural History Museum in San Diego and got an introduction from them and Dick Norris about the area we were about to explore. There are three main formations we focused on: the Stadium Conglomerate on the bottom, the Mission Valley Formation in the middle, and the Poway Conglomerate on top. As we walked along the trails, we were mostly seeing Poway cobbles from Sonora, Mexico that were smooth and reddish colored. As we walked up the hill a bit more though, we started to see the white chalky Mission Valley formation start to poke out from underneath the cobbles. When we were at the top of the hill, we looked across the canyon at the next hill to observe the color change from pale rock to red rock on top and see how the different formations stacked up on top of one another. The other piece of evidence we looked at was the vegetation as we noticed that certain types of vegetation grew on the different rock formations, allowing us to infer and visualize where the formation boundaries were based on the vegetation that was overlaying them.

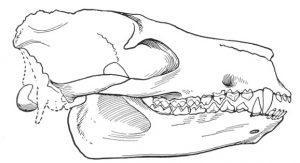

After our slightly sweaty expedition, we walked back to the park’s benches and looked at a box of fossils from the area that Tom had brought in. We saw a brontothere (a relative of the modern rhinoceros) jaw bone along with a protoreodont (early hoofed mammal) skull and tried to decide if they were herbivores or carnivores. We came to the opinion that the brontothere was the herbivore because it had flatter teeth while the protoreodont was the carnivore because it had sharper teeth and large front canines. We were wrong though! They were both herbivores! Tom told us that they just ate different types of vegetation, and flatter teeth were better for grinding grass while sharper ones were better for grabbing leaves from trees and sturdy bushes. Also, the point of articulation (where the lower jaw bone connects to the rest of the skull) on herbivores is higher up so all the teeth connect flat against each other at once, while on carnivores the point of articulation is in line with the teeth!

After we had our fill of Tom’s fossils, we headed to the Natural History Museum to walk around with Tom and Ashley. We looked at the amazing exhibits, and one that stood out was the walrus exhibit that showed how a lineage related to modern walruses had lost their molars and just fed with suction feeding while another lost their tusks so they could eat different foods and avoid competition! We spent about an hour marveling at all the fascinating displays before Tom and Ashely took us behind the scenes to look at some fossil specimens they had stored in collections. Tom specializes in cetaceans and marine mammals, so he showed us some amazing skulls of extinct dolphins along with hipbones from different species of walrus. There was one hip bone from a female walrus with arthritis that was very porous and had extra growths on it, which I had never seen before! It was crazy that we could learn about how uncomfortable a walrus from millions of years ago was from her preserved hipbone.

After we said goodbye to Tom and Dick at the museum, the rest of us headed to Casa Guadalajara for delicious Mexican food. There was a Mariachi band that serenaded the two people with birthday’s coming up! We left happy and well-fed, and then all promptly went to bed right when we got back to the hotel so that we could be up and ready for the next exciting day in the School of Rock!