The Long Game

Sitting at the top level of the JOIDES Resolution, I enjoy the abundance of sunlight. This is different than the lower levels of the ship which, when they have any windows at all, are small portholes or tiny windows in inside doors. Gazing out one of the large windows in this upper-level cozy conference room, I’m struck by how calm and gentle life is on the ship at the moment. At this late stage of Exp385T, the heavy work of tripping pipe and milling boreholes has stopped. Outside the window, the sky stretches endlessly, and a white blanket of bumpy clouds arches over a grey-blue ocean. As far as I can see, the ocean mirrors the texture of the cloud cover. Small chops of ocean water nudge, bump, and elbow the ship’s flanks. A seagull suddenly lurches into view outside the window, its knobby orange legs dangling below the graceful arch of its wings. I watch as it balances on unseen wind currents, perfectly centered in the window’s frame. Just as suddenly, the seagull dips down and away, leaving a window full of only ocean and sky again.

I have the good fortune to be sitting across from geophysics scientist, Keir Becker. He has graciously consented to an informal talk with my fellow education outreach officer and me. Kristen and I are curious about his take on the long view of deep ocean exploration. Kristen and I are also aware that one of the boreholes we have visited in this expedition has been important to Dr. Becker’s work, and we are interested in learning more. In what I promise will not turn into an interrogation, the three of us settle into the seating area beneath the window and start to talk.

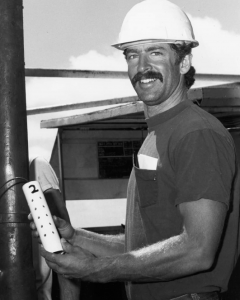

Dr. Becker’s career as a scientist started in the late 1970s and continues today. He has made the claim that a large part of his success is from being in the right place at the right time. This is an understatement, and it is deceptively straightforward. There is much more to his work than simply being around. Dr. Becker has been a consistent, steady presence in the world of deep ocean exploration for over 40 years. That is a professional history to be respected.

This current expedition is using a transit between regular expeditions to visit a borehole with a respectable history, too. This borehole, called 504B, was first drilled in 1979 and still carries the distinction of being the deepest ocean crust borehole. Today, 504B is considered one of the “best-studied holes in the history of ocean drilling.” One of Dr. Becker’s early ocean exploration adventures was at this site, and he has come back many times over the years.

In 1981, Dr. Becker and other scientists had a significant breakthrough at 504B. It had been known, due to research in the previous decade, that there is a significant amount of water that flows through the Earth’s crust and that this water is important to the processes that cool the Earth. What was unknown is precisely where in the crust the water moves, how it moves, and what role it plays in the Earth’s chemical and water cycling processes. Scientists are still learning about these unknowns today. Because the Earth’s crust is thinner under the ocean, scientists began the long game of drilling into the ocean floor at 504B and other sites to begin to answer some of these questions. They wanted to know how deep this complex system of rock and water cycling actually goes. They wanted to understand the structure of the crust and how water moved through it. What they found is that the water moves through a pretty shallow area of this part of our planet.

Dr. Becker and the other research scientists used 504B to conduct experiments studying the porosity of the rock that had been drilled through to establish the borehole. Using data on how porous the rock is at certain depths, the researchers identified three general zones of rock. At 504B, the porosity of the rock shows a dramatic decrease in porosity around 900 meters below the ocean floor. This was considered a breakthrough because it gave scientists a much better idea of how porosity changes with depth. This breakthrough led to two articles published in Nature magazine in 1982. The exposure was beneficial to both Dr. Becker and ocean exploration in general.

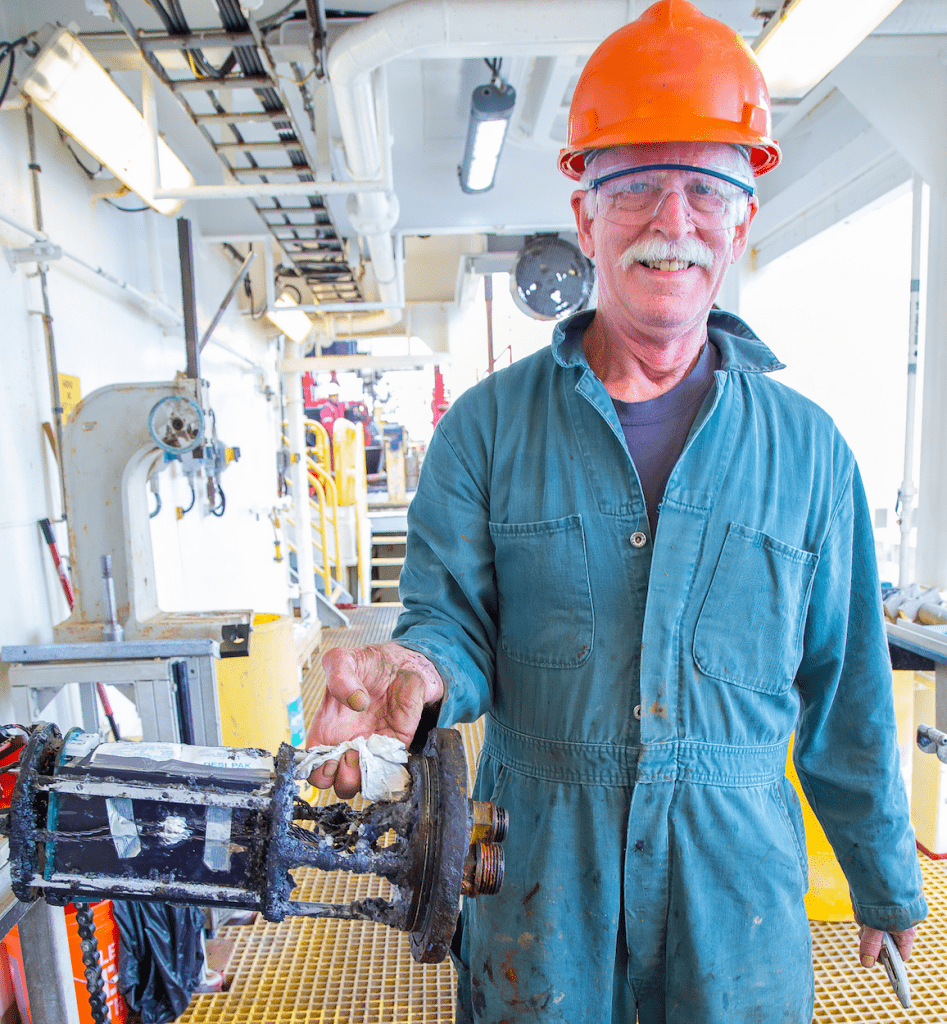

What followed was several years of expeditions around the globe, including occasional visits to 504B again. In the slow, steady process that is deep ocean research, Dr. Becker and his colleagues methodically added to the world’s understanding of our planet with each success and struggle. Over the years, scientists continued adding to the broader knowledge of the sub-seafloor, and periodic visits to 504B have contributed to this work. Our current expedition included an attempt to remove equipment and instruments previously installed in 504B and then gathering data to compare with other boreholes. In line with the way things go in deep ocean exploration, not everything that was planned came to fruition, but there is always something to learn with every expedition.

After a very pleasant hour or so, our conversation began to wind down. I looked again at the outline I had prepared for this meeting. The questions I had planned to ask had a few scrawled comments next to each one, but what stood out was the notes I had taken on all the things I hadn’t planned to talk about. My original thoughts in preparation for our talk lay underneath a layer of diagonal writing, scrawled in the open spaces and tucked into corners. I was looking at levels of information, slightly scrambled but oddly organized at the same time. I couldn’t help but compare it to the layers of experience Dr. Becker had been sharing with us. As I mentally ran through the things we had talked about, making sure I hadn’t forgotten to ask something important, I was struck with how deep ocean exploration is really a “long game.” This type of research stretches out in a long, patient arc. One group of scientists will set the stage for the other, each completing one step in the laborious, non-linear process of drilling through sediment and into the Earth’s crust. On each leg, researchers may set out to study one thing, as I did with my planned questions for our talk with Dr. Becker, but what the expedition returns with may very well be layers of information that refuse to be neatly tucked into categories. It requires a long game attitude to patiently tease apart all the things we learn and to make sense of them.

As the micro paleo tech and assistant curator on DSDP legs in the 70s, I was privileged to watch this “long game” begin in MANY areas. This was well written and is a story to be shared with students. They often believe we already know the science! It is just in a book to be learned, rather than an ongoing changing explanation of our observations.