Yinazao Seamount, and the Perils of Drilling on Hillsides

Well, it took more than a day to get core on deck!

Our first drilling site was out on the flank of Yinazao (formerly Blue Moon) seamount [It’s “new” name is its proper Chamorro name. I’ll try to use these names going forward for all the Mariana features we visit], about 900 meters below its summit. Yinazao sits in a little valley, so all the serpentine mudflows should end up stacking one atop the other at this site – or so went our thinking. So, it was puzzling that it was so difficult to get punched in with the APC piston coring tool – we had a bunch of empty cores to start each of the holes we tried, and the very first cores that we got were really confusing: what we got first was not serpentine muds, but classically red marine sediments – and only under those did we finally get serpentinized stuff (like in the teaser pic).

The other puzzle was the fact that we were getting up a whole lot of gravel: and the gravel created problems in the drilling, in that the gravelly sections of holes can cave in – and this appeared to be happening as our drilling penetration was very slow.

Staring at this core of gravel, which showed a clear pattern of finer grainsizes upsection, a very old light went on in my head, from way back in my first freshman-in-college geology class: I was looking at a turbidite!

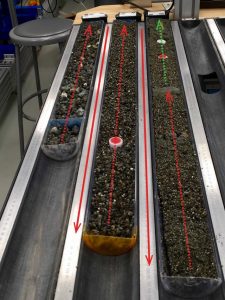

(Dotted arrows point upsection; solid arrows connect tops to bottoms; colors mark different sequences)

Turbidites are classic deep-sea deposits that develop at the bottom ends of sloped terrane in the oceans. Some kind of disturbance (an earthquake, or some other kind of downhill event – like a serpentine mudflow, even!) can trigger rapid downslope flows of sediments, which thanks to gravity and water get organized by grainsize, with the coarser stuff settling out first, and progressively finer stuff later on. The really fine, clay-size stuff gets caught up in the water column and whisked away by currents, leaving behind carefully graded, sandy-to-gravelly sediments. Wherever turbidites occur on the seafloor, they tend to happen over and over again, often at different scales, so you get layer after layer of them, like the two different turbidites (see the red and green arrows) in the picture above.

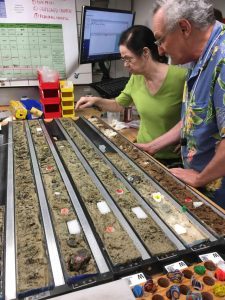

These turbidites helped explain (for me at least!) why our drilling had been so difficult: the little valley we were in wasn’t just catching mudflows from the seamount – it was catching everything, from slumps of red seafloor sediments to old serpentinite muds that had been winnowed and reorganized by turbidity currents. At a Crossover Meeting on the Core Deck, we discussed as a team what we were seeing in the cores, and what was likely with continued drilling at this flank site, and there was consensus, per the advice of the drillers, that if we hit more gravel, we had to move. And currently, we are moving, to (hopefully) easier and more productive drilling at Yinazao’s summit.

Although the coring here was slow and difficult, it did afford me the opportunity to again participate in and appreciate the “dance” precipitated by the sound of “Core on deck! on the ship’s intercom: everyone racing in hard hats to the Catwalk, the IODP Techs marching in the core tube, the clanging and banging from the corecatcher table as one of the techs extracts and collects the materials in the Corecatcher.

My part in this “dance” is to take possession of those core sections on which we are seeking to measure the Interstitial Water. I march these down to the Geochemistry laboratory, where we squeeze them to extract their pore fluids, which are then parsed for a range of different shipboard analysis, as well as the proposed geochemical work of over a dozen different members of our Science Team. As the porefluid compositions of the Mariana serpentinite seamounts are known to be unusual, there is considerable interest in the fluids – so we’re taking multiple “squeezer” sections from every core returned.

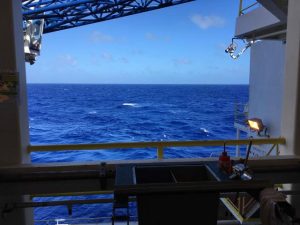

In our busy periods on ship, you can completely get caught up in the work and excitement of seeing newly recovered samples. But it’s important not to miss out on the other amazing things around you, like the remarkable blue of the Pacific at midday, and of course the sunrises, which have all been different, and, each in their own way, spectacular.

More from the summit of Yinazao, when we get there!