Journey Through the Midnight Zone

Today during one of my live classroom broadcasts, a student asked what it felt like to be higher than Mount Everest. The student was referring to our location above the Mariana Trench–the deepest part of the ocean (35,827 feet deep), often contrasted with Mount Everest since its the highest point on earth (29,035 feet high).

So in other words, what does it feel like to be floating above the deepest place we know of on the planet?

(Left: the observation camera catches a glimpse of a curious squid about 200 meters below the surface)

Technically, our ship is not directly over the Mariana Trench right now; rather we are traveling over the Mariana Forearc, the shallower ridge due west of the trench where the unique serpentinite mud volcanoes form that our scientists are so interested in. Still, our target volcanoes are a good 6,000 to 18,000 feet below the sea surface, depending on the site.

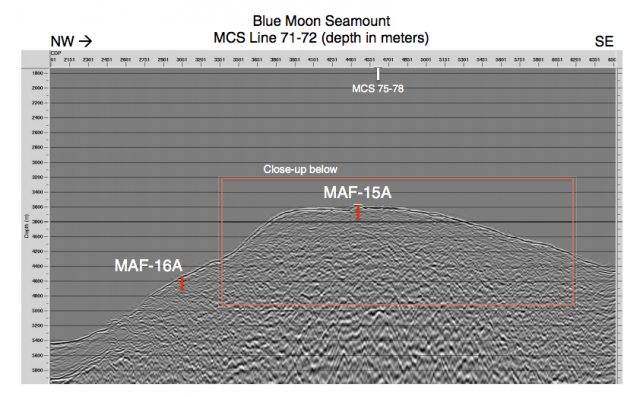

A side view schematic of one of our coring sites, Big Blue Seamount, whose base reaches 5400 feet below the sea surface.

In other words, there’s a lot of ocean between our ship and the seafloor. It’s hard to truly understand just how much water that is, but being aboard the JOIDES Resolution has at least given me a bit more perspective. For one, it takes several hours for the ship’s drill and pipe to reach the seafloor and return back to the ship. You could fly across the entire United States in the same amount of time it takes us to reach the seafloor and return in some cases.

Sometimes, the drill technicians lower a camera down with the pipe when they need to locate the re-entry cone (the device that keeps our drilled hole open and visible on the seafloor), so it’s possible to watch the camera travel on its several hour journey down to the seafloor. I can’t say I’ve sat through the whole adventure down and back, but I’ve spend a few good chunks of time observing the camera to see what the ocean looks like several hundred to thousands of meters deep.

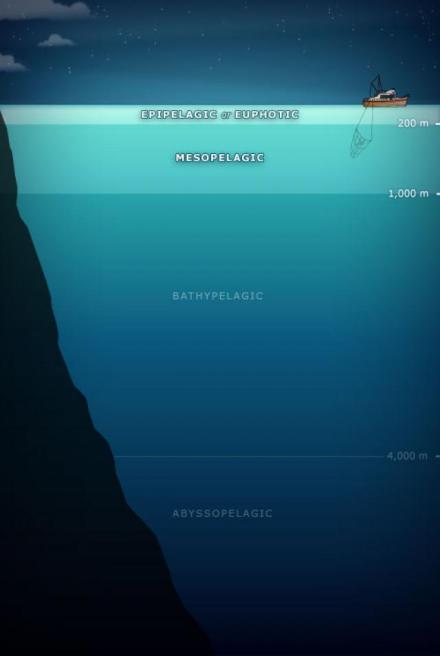

Near the sea surface (anywhere down to about 100-200 meters) you are likely to spot several kinds of fish—tuna, mahimahi, trigger fish, and others—plus squid and other interesting creatures zooming past the camera. On the seafloor, you can often pick out invertebrates like mussels or crabs, as well as sponges and mats of archaea or bacteria. But in between, in what’s called the Bathypelagic Zone (or my preferred name, the Midnight Zone), there’s a lot of nothing. Okay, not really nothing, but most things below the photic zone (the area of the ocean that light can penetrate) are tiny and/or hard to see. Little shrimps, zooplankton, bacteria, and tons of ‘marine snow’. And a lot of watery darkness.

The bathypelagic zone (Midnight Zone) lies more than 1,000 feet below where sunlight can penetrate. Our camera passes through this zone to reach our target seamounts on the Mariana Forearc. (Image: Te Ara Encyclopedia of New Zealand)

Just as observing stars on a clear night can be humbling to the ego, watching the camera plunge deeper and deeper into oceanic darkness (save for the bit of light projected from the camera itself) for hours on end has altered my perspective on the scale and nature of earth’s processes. After five weeks on the ship, when everyone is fairly set in their daily routines and the novelty of living at sea has faded, I think it’s these random observations that become more meaningful. Watching endless rolling waves meet a surreal sunrise; touching rocks that have traveled from deep within our planet up through a mud volcano and into our core sample by sheer chance; and yes, even watching a camera go down and down through a seemingly empty ocean for hours, all leave their imprints on the mind.

In the few weeks that remain of Expedition 366, the science party will be working hard to finish their analyses of our core samples and write their assigned reports before we reach Hong Kong. There’s no question that this expedition has uncovered exciting new information about how subduction zones function, how serpentine muds are formed, and how life may have started in these types of environments. But what you won’t read about in the reports or scientific papers from this expedition are the moments of clarity, humility, shared laughter, and solitude that subtly changed each of us along the way. For that, you’ll have to ask for the unwritten story—or take a similar journey yourself!