Atlantis Bank: A Mountain Under the Sea

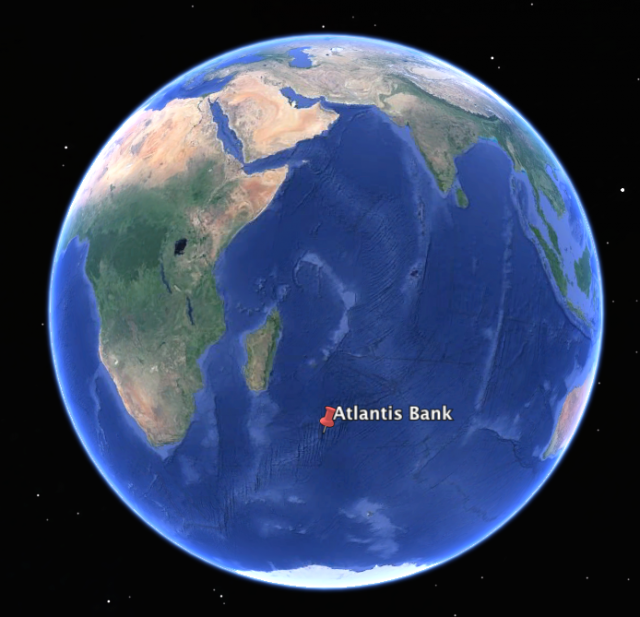

For over a month now, the JOIDES resolution has maintained its position in the southwest Indian Ocean, 700 meters above Atlantis Bank. This undersea mountain was named in 1986 by one of our co-chief scientists Henry Dick, “we found a block that had been lifted up to sea level, it was an island at one point” says Dick, “so we named it Atlantis Bank after of course the lost city of Atlantis”.

However, the story of the rock we’re drilling though started 12 million years earlier when it cooled from magma deep beneath the seafloor. This was the same time as Earth’s magnetic field was in the process of flipping away from a state where compasses would have pointed towards the south pole instead of the north. Tiny magnetic minerals within the rocks of Atlantis Bank act as miniature compasses and record this shift towards a magnetic field with a direction similar to today.

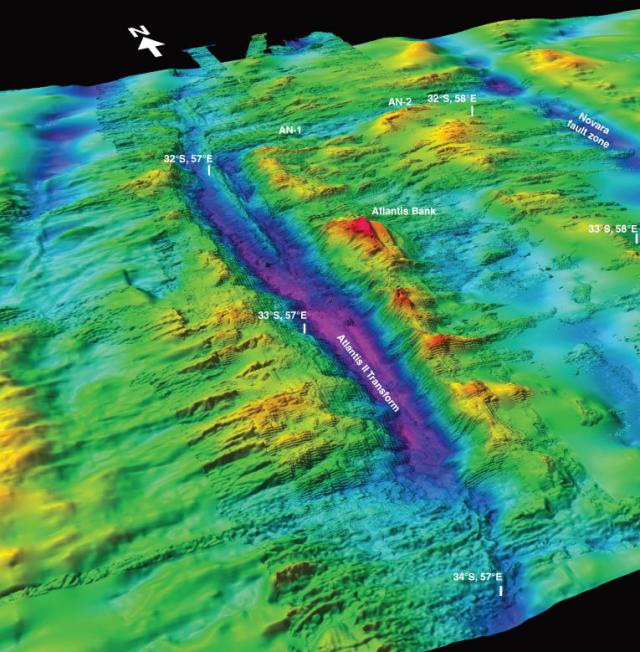

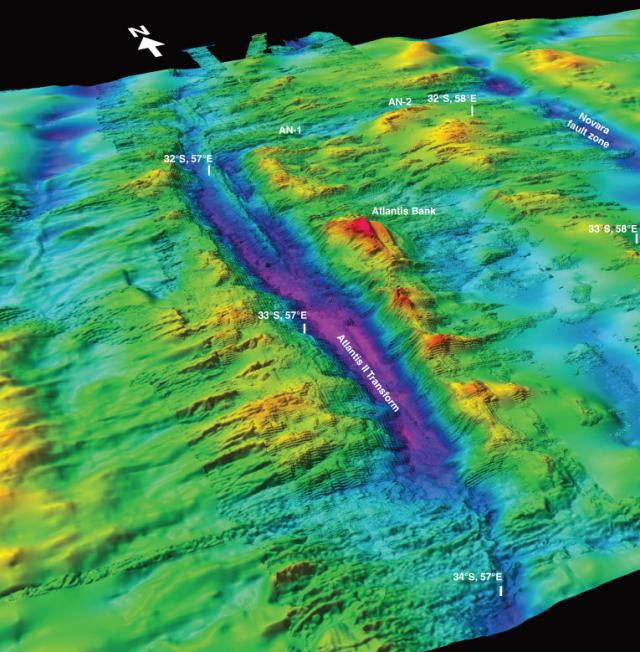

We’re in the middle of the ultra-slow spreading southwest Indian Ridge and something very interesting happens at these slow spreading mid-ocean ridges. Geologist Mike Cheadle explains, “there’s not enough magma coming out of the mantle to fill the gap created when the tectonic plates spread apart and so instead the rocks have to break and extend along one of the biggest faults seem on the Earth”.

Henry Dick continues the story, “then what happens to the deep crust is really strange, it goes up, and goes up, and goes up and winds up only a kilometre or so below the sea surface”. “This is a bit like finding a brick of lead floating in your bathtub” muses Dick, “the scientific community has not come to a consensus on why this happens”.

Uplift continued until Atlantis Bank was brought to the sea surface and the waves eroded the upper rocks, creating a flat top to the platform. As Dick points out, even though it is now 700 meters under the sea, it still resembles a beach “like the rocky coastline of Maine except for when you try to stick a mechanical arm into the sand, you find it’s limestone”. Atlantis Bank has sunk since then but even today remains 3 kilometres higher than scientists expect to find ocean crust of this age.

This process of faulting away the upper crust removes the finer grained volcanic rocks that normally lie above deeper crustal rocks; “this is enormously important because the volcanics are exceedingly difficult to drill though” says Cheadle. “It’s called a tectonic window and gives us a shortcut to the lower crust and brings us much closer to the mantle”. This is why many think this may be the place we eventually drill beyond the crust for the first time. It’s still far too early to say with any certainty if the hole we’re currently drilling (affectionately named U1473a) will ever reach to the mantle but it’s in one of the best places we know of to make this tremendous task as realistic as possible.