“Core on Deck!”

A tinny crackle sounds over the PA system before the announcement that our wait is over. The gaggle of scientists in the lab beside the “catwalk”—the place where the cores are first received—dons hardhats and safety glasses, excited to observe the arrival of our very first core of Expedition 382, Iceberg Alley and Subantarctic Ice and Ocean Dynamics.

![A team of female technicians in hardhats and safety goggles slicing up the core [Credit: Marlo Garnsworthy]](https://joidesresolution.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/03/DSC_0844-1024x683.jpg)

But there is an eighth smaller section called the core catcher.

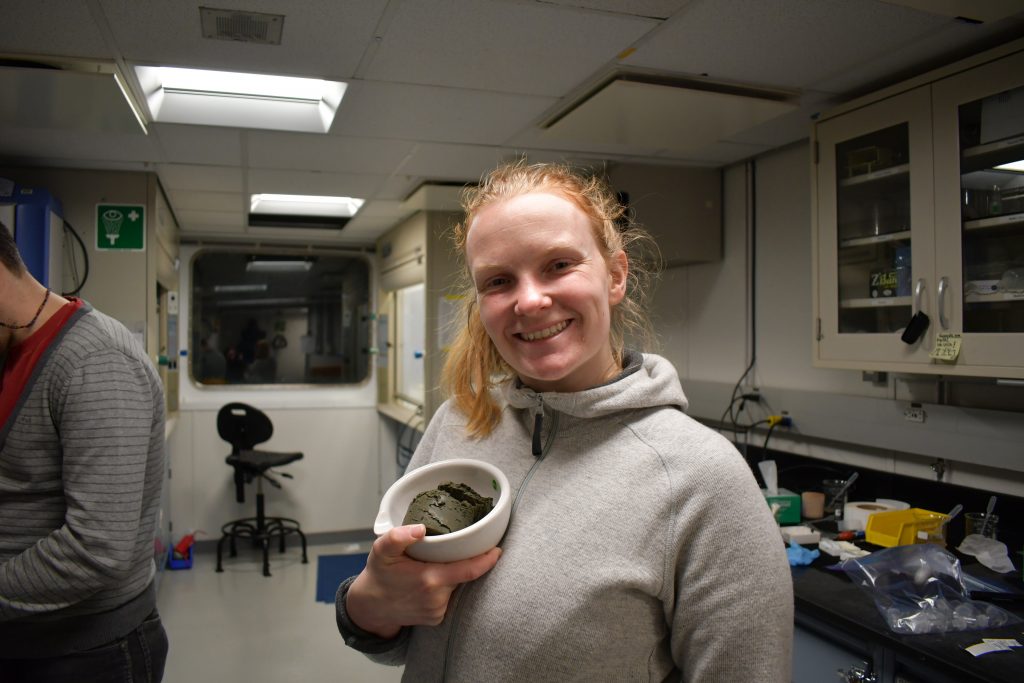

I visit with biostratigrapher Ivan Hernandez-Almeida, who is very neatly spraying a sieve full of mud, to find out more.

“We are…” he searches for the word in English, “the front of the army?”

“The vanguard?” I ask.

“Yes, the vanguard of the sampling process. By the time the other labs get their sediment, we have probably already established its date.” He explains how, by identifying the various species of microfossils present, his team can establish a preliminary date range for the material in each core section.

“But first we must torture the microfossils.” He explains how they use hydrochloric acid to remove calcium carbonate or hydrogen peroxide to remove any organic matter and leave only the intricate skeletons of radiolarians and diatoms behind. Forams require only washing, and larger zooplankton are collected using a sieve. (Hence Ivan’s excellent water-spraying.)

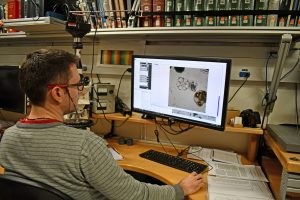

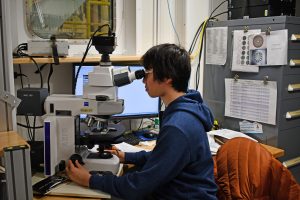

They then create slides and study the microfossils under a microscope.

“What problems can you encounter?” I ask.

“Preservation and abundance matter,” says Ivan. Sediment can also be washed away by ocean currents, creating what’s called a hiatus in the sedimentary record. He likens lineages of species over time to generations in a family.

“If we have the grandfather then the grandson species, but we have no father in between, we ask, ‘What happened?’” Something must have occurred to remove the sediment in between deposition of the “grandfather” species and the “grandson” species, such as strong ocean currents eroding sediment away.

Thankfully, using multiple species to date the sediment, together with the paleomagnetic record (which we’ll learn about in a later blog post), can create a “multi-proxy” and very accurate dating of the material. All of this information will be used in conjunction with other data about the properties of the sediment to establish when it was deposited and where it came from.

This is only the first of numerous procedures our Iceberg Alley team undertakes to describe and measure the physical and chemical properties of the sediment, looking for the “iceberg-rafted debris”—the dirt and rocks carried by icebergs from Antarctica—we seek.

The PA crackles again. “Core on deck!”

The Night team has worked all night and through to noon, and despite the drill string becoming stuck later in our shift, there is no slowdown for the scientists. There is plenty of material waiting for description, measuring, and analysis waiting for the eager Day shift.

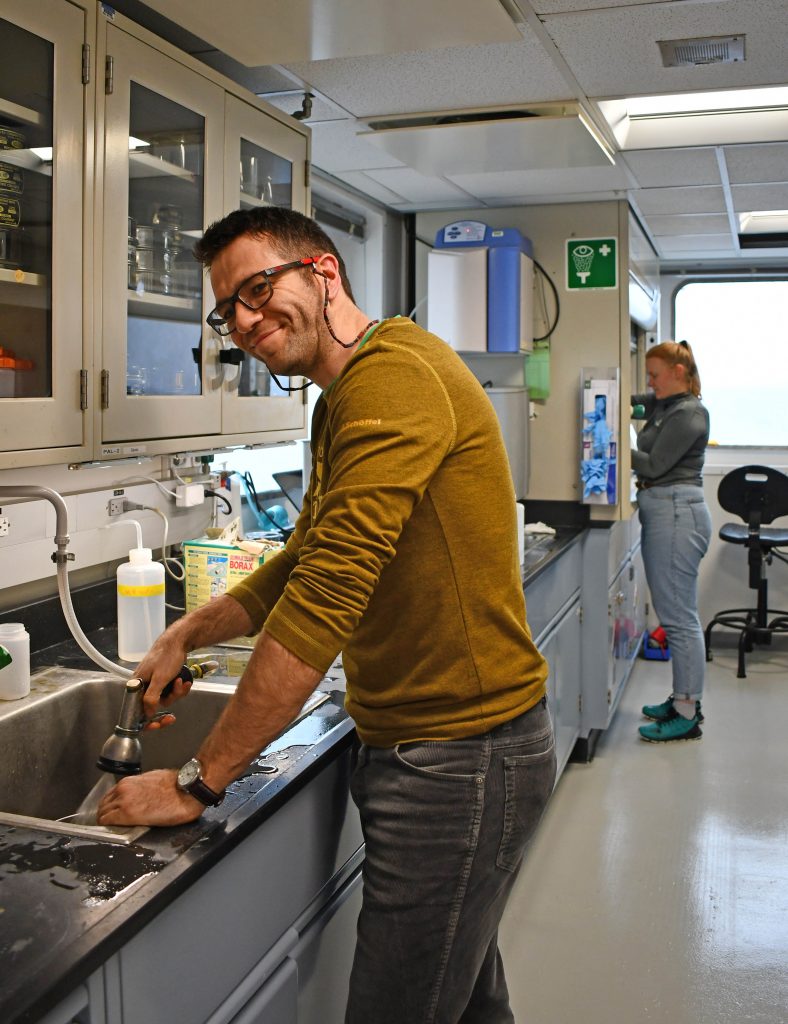

The night-shift biostratigraphy team: Ivan Hernandez-Almeida, Frida Snilstveit Hoem, and Yuji Kato [Credit: Marlo Garnsworthy]

Thanks for such an informative update on progress so far – interesting stuff!