Catching Up At Octopus Mound

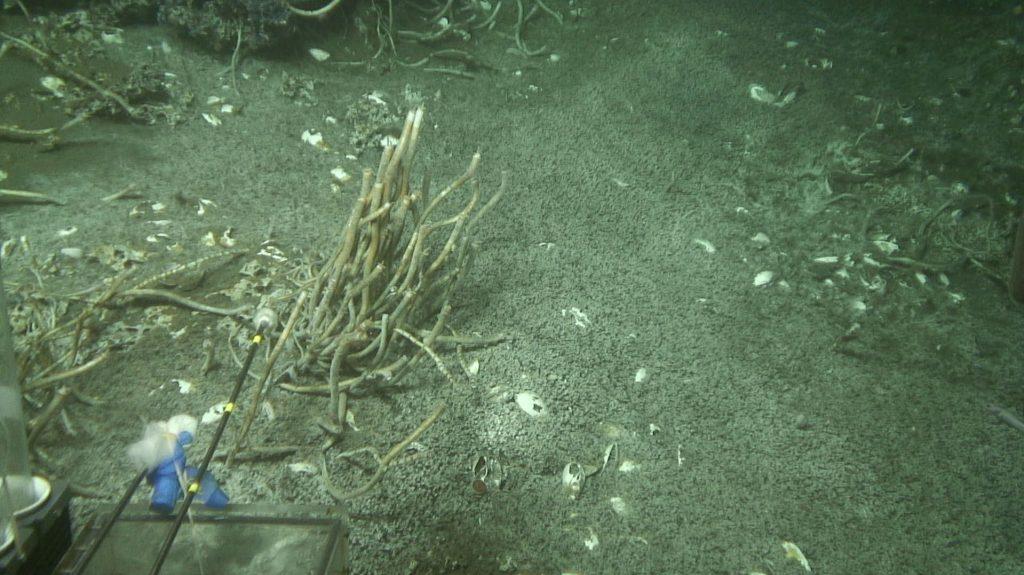

The JOIDES Resolution has started to drill at a new site: Central Seep, a.k.a Octopus Mound, a cold methane seep centrally located in Guaymas Basin, approximately equidistant from Baja California and Sonora. Octopus Mound was mapped in 2016 with AUV Sentry and visited by submersible Alvin. It contains classic cold seep fauna with methane-oxidizing Lamellibrachia tube worms, ampharetid worms, galatheid crabs, and lots of seafloor carbonate.

At a safe distance of three miles from the methane-rich and potentially explosive mound, we are drilling into a shallow gas-rich zone, presumably with methane hydrates not far below the surface, but no rocks or hard minerals. Although this is supposed to be a cold seep site, the high heat flow of Guaymas Basin is instantly noticeable; the temperature goes up by approx. 20°C over 100 meters. No proper cold seep would do this. But Octopus Mound hides a secret that will by now not surprise anyone — it sits on top of a very deep sill. No worries, we will not drill it.

While methane-soaked cores are coming up, some microbiologists are still frantically chiseling the Ringvent cores into small bits and divide them up for a grand communal microbiology project — a multi-investigator assault on potential microbial life that might survive or thrive in the Ringvent sill. Recruited by Chisel Masters Ginny and Yuki, the co-chief is now hammering away at rock-embedded sediment veins — they are easy to crack but take some time to extract. A somewhat determined facial expression is also said to be essential when cracking rocks.

This special animation program of rock exfoliation ergotherapy is brought to you by IODP, to enhance hard rock appreciation among sediment microbiologists. The unintended side effect will be a renewed appreciation of soft sediments.

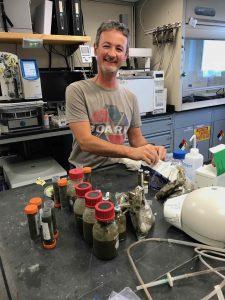

When the rock is finally ground into reasonably fine chunks, it is mixed into selective media that promote the growth of anaerobic deep subsurface microorganisms, such as sulfate reducers or methanogens. The resulting deep rock smoothie is divided up among the respective science parties who want to try their luck; something should ultimately grow. Laurent is looking forward to a nice crop of subsurface microbes.

This blog post first appeared on Oct. 25 on my daily blog of EXP385. Make sure to go to expedition385.wordpress.com to read the latest updates of this expedition!