What’s In a Name?

I cut my journalistic teeth in a newsroom lorded over by a cigar-chomping editor who breathed down reporters’ necks on deadline. He instigated cutthroat competition, warning us about getting scooped, instilling in me the need to be first.

That was long ago and far away. But still I want to be where the story is live and late-breaking.

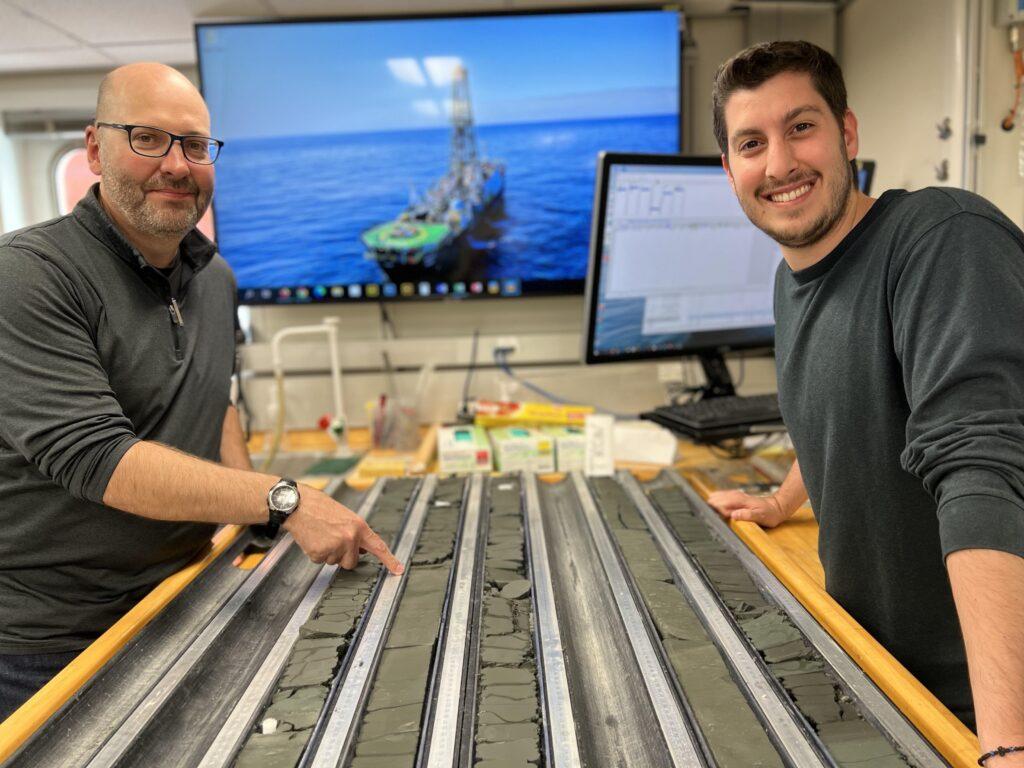

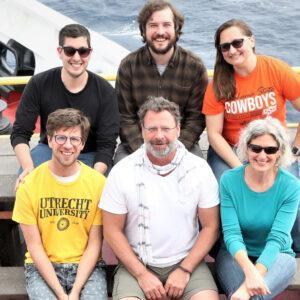

That’s why, on the JR, I lurk about in the narrow, microscope-lined cul-de-sac on the port side of the main lab. Here, an elite six-pack of micropaleontologists adroitly assigns ages to cores. Co-chief Scientist Steve Bohaty calls them “the time department” for good reason.

While the rest of us bite our nails and wonder if a sample is early Paleocene or late Cretaceous, team micropal is on the move, smearing bits of fresh core on slides and having a first look. They determine where we are in geologic time by comparing which tiny fossils they see to known age ranges of species.

Nannofossil expert Odysseus Archontikis is an early-career scientist, a first-timer on the JR. Imagine his delight, on day-eight of drilling at our first site on the Agulhas Plateau, when he exclaimed for all to hear: “We have crossed the K-Pg boundary!”

Finding the Cretaceous–Paleogene (K-Pg) boundary—which marks a mass extinction event of 66 million years ago, when much of life on Earth was exterminated, including dinosaurs—ranks as a highlight of Expedition 392.

“We knew we would be drilling through that time interval,” Steve said, “but didn’t know if the boundary itself would be preserved on the plateau. That was unexpected and exciting.”

Other top hits: unearthing red-striped sediment from the Cretaceous period’s enigmatic Campanian age, when the Earth’s greenhouse conditions were slowly cooling; and recovering a green rock unit associated with intruding fingers of hot magma.

This list is by no means complete. These two months of drilling at sea represent just the tip of the discovery iceberg. Scientists from all over the world will have access for eons to samples recovered during Expedition 392.

“That’s often when you find out exciting things,” Steve said. In fact, a lot of his own initial studies were based on cores that were decades old. Originally trained as a micropaleontologist, Steve made significant contributions to that field despite research questions leading him off in other directions over the past years. A decade ago, colleagues honored his micropaleontology work by naming a diatom species for him: Fragilariopsis bohatyi.

When I asked him about it, I’m pretty sure I saw him start to blush. He escaped the conversation with a promise to send me related research papers—a self-effacing strategy if ever I saw one.

It was from a 2012 article published in the journal Micropaleontology that I learned all about F. bohatyi. It’s where I found out “The epithet honors Dr. Steven Bohaty, who first documented this species (in 1998). . . and for his contributions to Antarctic diatom biostratigraphy.”

Steve is looking forward to returning to his microfossil roots when this expedition ends, with a move to a professorship at Heidelberg University. His commitment to involve young scientists in scientific ocean drilling runs deep. Expedition 392 includes a vibrant mix of scientists of many nationalities in all phases of their research careers; some senior, like himself, and others, like Odysseus, with many nautical miles to go.

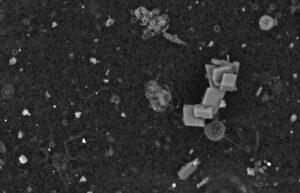

Odysseus was on his way to becoming a volcanologist when a crystalline coccolith caught his eye. He never looked back. He was smitten by the beauty and intricacy of these calcium carbonate scales, these armor-like structures produced by single-celled phytoplankton called coccolithophores.

What’s not to love about marine algae, one of Earth’s smallest life forms? “Zillions—and even more!—live in the world’s oceans,” Odysseus said. “And when they die and float down to the bottom, they make sediment that accumulates and accumulates.”

He’s equally intrigued by living plankton, sitting as it does at the base of Earth’s food chain. He’s got big questions, such as, how will they respond to climate change, to ocean acidification? How they respond likely foretells how the ecosystem at large will respond.

Seeking answers, Odysseus recently found himself staring at an image on the JR’s scanning electron microscope, pondering a spider-like coccolithophore.

The organism had been floating in seawater that Odysseus collected in a bucket during transit from one drill site to the next. He’s working on a side research project in his spare time, after 12-hour shifts spent sco uring core samples for coccoliths: He wants to know how climate change has shaped life, shaped evolution.

uring core samples for coccoliths: He wants to know how climate change has shaped life, shaped evolution.

Speaking of shape. . . Odysseus had never seen a morphology quite like this. The coccolithophore had a bulbous body, covered by coccoliths, with a few unusual structures attached.

Is it possible, he mused, that the organism was not yet described in the literature?

I blurted, “Will you get to name it?!” I told Odysseus about an arachnologist who named a new spider species after Neil Young.

The young scientist’s expression, so animated while nattering about nannofossils, went blank.

Of course I started schooling this Oxford University PhD candidate—he of brilliant mind and with a heart of gold—about my favorite singer/songwriter. I rattled off some hits—Like a Hurricane, Cinnamon Girl. And, given our locale, the lesser-known Ocean Girl.

I told him Neil is an environmentalist who has provoked listeners for half a century with lyrics like, “look at Mother Nature on the run / in the 1970s.”

He’s known for his high, shaky tenor, I added. And for railing against fossil fuels.

Mercifully, the micropaleontologist and I found common ground. Coccoliths, Odysseus ventured, are carbon-absorbing machines—nature’s most prolific consumers of atmospheric carbon dioxide.

Coccolithophores play a key role in the functioning of the global carbon system, helping tamp down atmospheric CO2 concentrations over the long term by providing a sink for emitted carbon, thus mediating the effects of greenhouse gas emissions.

That is all very well and good. So too is the fact that Odysseus is on his way to answering important questions while discovering many a new species. And just maybe, in some not-too-distant carbon-neutral future, this passionate young researcher will have a nannofossil named for him—although, as he cheerfully pointed out, virtually no one would ever be able to pronounce “archontikisii.”

You heard that here first.