Reaching out to the world from onboard the JR

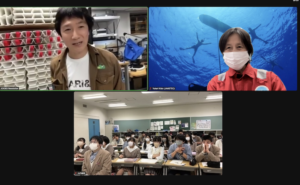

Portuguese students express gratitude after a live ship-to-shore tour.

Expedition 397 ship-to-shore outreach tours have connected with people around the world.

A lot of people.

Across 86 live Zoom tours, around 3,505,000 people from four continents got to peek onboard and see:

- cores coming up to the surface,

- technicians cutting and splitting them,

- physical properties specialists ushering them through multiple instruments,

- stratigraphers attempting to correlate them,

- sedimentologists describing them and then moving them through the image logger and the “section half multi-sensor logger” (the dreaded SHMSL),

- paleomagnetists feeding the magnetometer,

- micropaleontologists peering into microscopes, and

- geochemists pounding samples and squeezing out whatever water they could.

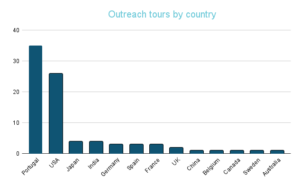

These tours engaged children as young as 5 years old, students in every grade, college kids and adults of all ages. By far the greatest demand for tours came from Portugal, where teachers and students alike were proud to see a co-chief and a sedimentologist from their country onboard and also to learn that such important science was being undertaken so close to their coast. While Portugal had the most tours, China ran away with the total audience figure. By far the largest participation — ever — for a live ship-to-shore tour was the event in China, beamed to six schools and live streamed to the public.

We had children from after school programs and clubs and from a kid-produced radio show. Oceanography and paleoclimate classes from community colleges, state universities and private liberal arts colleges — plus one art school — augmented the semester with a virtual tour.

Adults joined because they attended an event at a museum (in the United States or Japan), clicked on the Xinhua news agency live feed (in China) or Zoomed in to catch a glimpse of a loved one during two “friends and family” tours for the scientists and techs onboard (of course there were some kids on those as well).

Expedition 397 reached audiences in: Australia, Belgium, Canada, China, France, Germany, India, Japan, Portugal, Spain, Sweden, the United Kingdom and the United States of America.

In the United States, participants were in Alabama, California, Illinois, Indiana, Iowa, Massachusetts, New Mexico, New York, Ohio, Oregon, Pennsylvania, Texas and Washington.

All of the scientists contributed to outreach in different ways. The two co-chiefs and the staff scientist plus 18 other members of the science party all hosted or co-hosted at least one tour. Audiences learned about the ship in eight different languages.

The ship is now in the Mediterranean Sea en route to Tarragona, Spain with 6,176.7 meters of sediment packed up in the hold below. Already 10,000 samples have been taken and the scientists will meet in Bremen, Germany in about six months to take the samples they’ll use for their post-cruise projects.

After a moratorium period, the cores from Expedition 397, like all the cores from past cruises, will be available for scientists anywhere to investigate.

There’s a good chance Expedition 397 outreach will have lasting impacts.

In 5-10 years, some of today’s early-career researchers could get inquiries from Portuguese grad students who want to see for themselves what secrets the Iberian Margin has been keeping for millions of years.