An Experienced Voice

Read part 1 here.

Micropaleontology is more than just science—it is the ability to listen to voices of the past. Sounds poetic, right? It is impossible not to feel thrilled when you observe a microfossil under the microscope for the first time. It still happens to me almost every day when I look at the radiolarians recovered during this expedition: shells with complex patterns, yet harmonic despite being just a single cell.

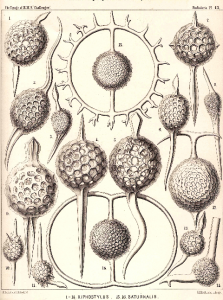

I often daydream about the reaction of the person who first observed and described a radiolarian. I really wish I could have been there, whenever it happened. I imagine meeting one of those 19th century scientists and having a nice chat about microfossils. Well, perhaps “scientist” is not the best description for them. They were naturalists and artists, passionate about the microscopic world beyond our sight. They were naming the unnamed. What would they think about the science we do nowadays? I would like to hear their voices, too…

I meet Herr Ernst Haeckel* at the bridge. With grey hair and beard, a bit taller than me, he is wearing a dark jacket and pants: elegant but also functional for life at sea.

“Guten Morgen, Herr Haeckel!” I say.

He nods, and we shake hands. He looks around and touches a porthole and the handrail. He knocks the wall. Clonk, clonk. “Metallic,” he says. “Looks robust and resistant, but I still prefer the warmth and elegance of the wood from the H.M.S. Challenger. “

We enter the core lab. The weather is nice outside, the sea is calm, and the first meters of seafloor are very soft. Cores come up very quickly. A few hours rest after being ripped from the seafloor, adapting to room temperature, and the cores are split into two halves. Activity in the core lab becomes frenetic. It seems the cores float in the air, passing from hands to hands, going from one place to another. Everything is perfectly synchronized, like choreography practiced many times. A half-core lies on a table, and two scientists argue about the color, like doctors discussing a patient’s diagnosis. The cores are placed inside dark boxes, like coffins, and come out apparently intact after a few minutes.

“What are they doing with the sediment?” Haeckel asks, very intrigued. I explain to him all the analyses: radiation, magnetic susceptibility, seismics… He seems a bit mind-boggled—too many new concepts.

I take him to the micropaleontology lab. This corner is usually less crowded; only a few people work here. I show him the lab where we prepare the slides. A piece of sediment, a metal sieve, and running water to wash the sample. A pipette, a glass slide, a few drops of sediment diluted with water, and a cover slip. Everything made in just a few steps using our own hands. No scanners or computers. The same procedure used a hundred and fifty years ago; the technique has barely changed. Once the slide is glued and dry, we take it to the microscope room.

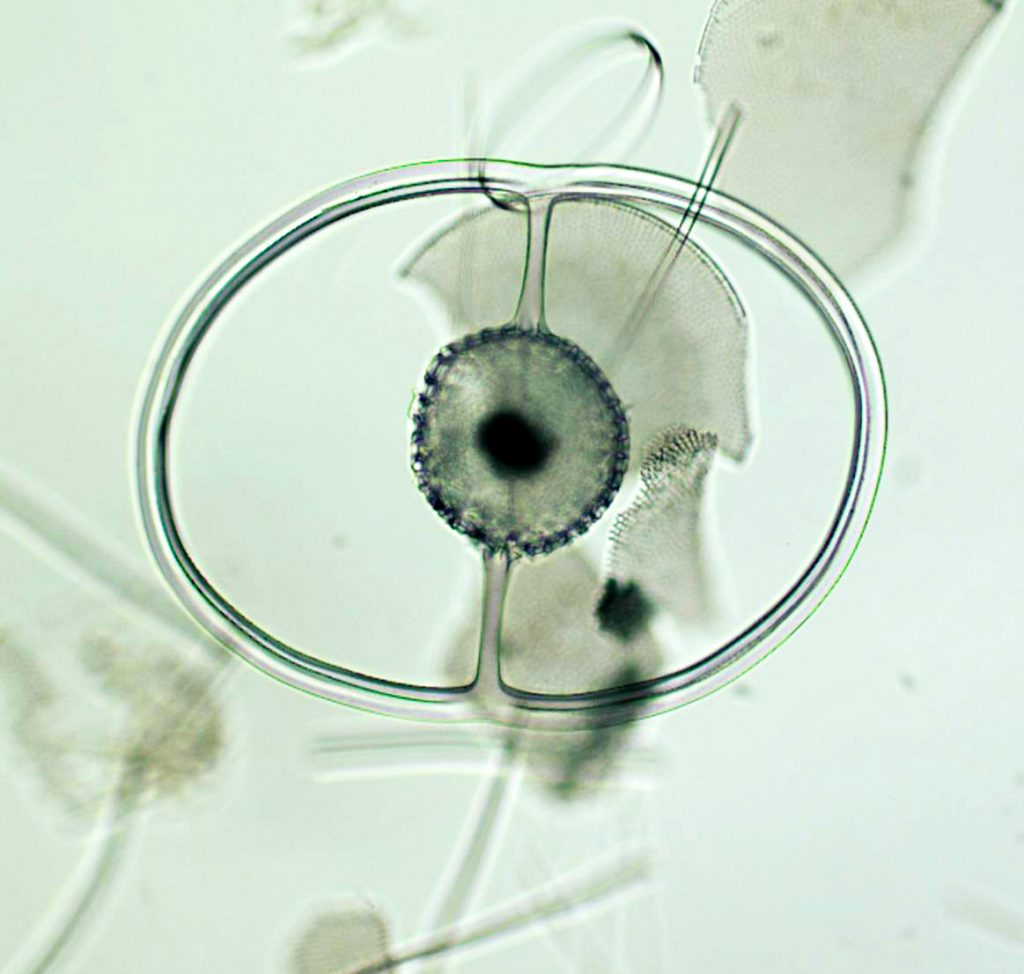

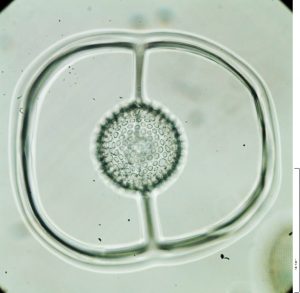

Normally, there is little movement here. We spend hours in front of the microscope. It is peaceful and quiet. I invite him to take a seat. I adjust the chair to his height. I explain the basics, how to adjust the focus and light and how to move the slide. He picks up the concept very quickly. He leans closer, showing a bit of caution as his eyes approach the binoculars. Then both of us are silent for a few minutes. He relaxes his back and shoulders. He sighs. Familiarity makes him a little more comfortable.We remain in silence for a while. Only his hands make slight movements from time to time to touch the focus knob. With delicate movements of his fingers, he navigates through the slide. He has not forgotten how fragile microscopes are. He speaks for the first time in ten minutes.“Beautiful,” he says. “Dictyopodium trilobum…”The name sounds familiar, but I’m not sure. I have a quick look at some papers on my desk, but I do not find it. Instead, I grab a book from a shelf above our heads. The title is Report on the Radiolaria collected By H.M.S. Challenger during the years 1873-1876, published by Herr Haeckel in 1887. I find the name and look at the illustration.

“Now it is called Pterocanium trilobum,” I reply. He mumbles something I do not understand. I explain to him how some species names have been changed since the early times of micropaleontology.

He continues looking through the microscope. “Two half-circles connected to a central sphere by two polar spines,” he describes.

“Symmetry perfection,” I say.

“I always liked the idea of a radiolarian that wished to become a planet but ended up buried in the bottom of the sea,” says Haeckel.

“Saturnalis circularis.”

He chuckles and nods. “At least, there are a few things that have not changed much through time.”

*Ernst Haeckel (1834-1919) was a German marine biologist, naturalist, and artist, among other things, and he is known for discovering thousands of new species, mapping a genealogical tree relating lifeforms, and much more, including his exquisitely detailed illustrations of marine organisms. While some species names have changed, micropaleontologists still refer to his works today for help with species identification.

Nice weaving of a story, bringing in the pioneers of the field and trying to imagine their reaction to our modern world and techniques.