Core on Deck!

The first core arrived on deck at midnight just in time for the shift change; fresh seafloor sediment from 1,600 meters deep! Here, the core barrel has been lifted out of the drill pipe and is carefully lowered to the drill floor; the sediment core within is protected by a transparent plastic casing, the core liner.

The sediment-filled core liner, 9.5 meters long, is carried in procession to the catwalk — an extended porch outside the core lab — and carefully placed into the custom-made core section holder, complete with small work stations holding towels, cleaning supplies, markers and small tools.

Next, the core is divided into 1.5-meter-long sections, numbered one to six. This first core, a.k.a. mudline core, has penetrated the seafloor halfway. The muddy seawater in the top three sections is discarded, but the bottom three sections contain seafloor sediment, organic-rich diatom ooze. Three times 1.5-meter sections means that the bottom of this first core is located at 4.5 meters below seafloor; the next core will continue down this hole and start from this depth. In this way, holes are extended step by step in 9.5 meter intervals, as long as the sediment is cooperating.

Core segments are closed with plastic caps and immediately carried inside for cataloguing. To prevent mishaps in labelling and bookkeeping, the very first step before anything else is the laser labelling machine that engraves the core and section number into the plastic core liner of each segment, twice.

Meanwhile, small sections of the core have been set aside for porewater squeezing, to determine essential chemical signatures of the interstitial water between the sediment particles; these chemical signatures define the environmental conditions and ecological niches for sediment microbes. Near-surface sediments are quite soupy and therefore it is easy to extract lots of porewater, but deeper sediments are harder and drier, and become more difficult to extract. Here, inorganic geochemist Toshiro Yamanaka, from Tokyo University of Marine Science and Technology, is inspecting the first porewater residues; these sediment cakes that are left after porewater extraction remain useful for other analyses and are carefully catalogued as well.

The well-rested sedimentologists of the night shift take

over and say “ohhhh” and “ahhh” with delight.

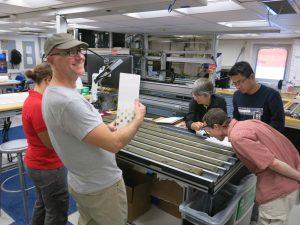

Now, the well-rested sedimentologists of the night shift take over and say “ohhhh” and “ahhh” with delight. Finally! Scientists from other fields are drafted into helping with core descriptions and documentation. Here Joann Stock, who normally deals with deep tectonics, hard rock, and deep time, looks at a freshly split core of organic-rich, beautifully laminated sediment that was deposited just a geological heartbeat ago. Two hard rock geologists, Khogenkumar Singh from India’s National Centre for Antarctic and Ocean Research in Goa, and co-chief Dan Lizarralde from WHOI, are gazing at this unfamiliar material. Technically this is very young rock with a fairly high water content that has never seen heat nor pressure in its short life…

Ivano Aiello, one of our super-experienced sedimentologists and veteran of many IODP cruises, is waving the sediment color chart that will guide our untrained eyes and help to distinguish the fine shades of green, grey, brown, olive, slate, ash… there are not enough words for these artworks of nature. Ivano has just recently sailed on a very stormy JR expedition in Southern Chile and enjoys the calm, warmth and sunshine of Guaymas Basin.

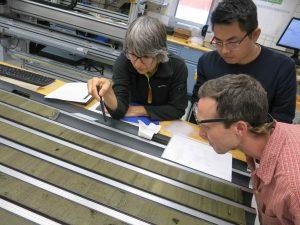

Super-experienced sedimentologist Kathie Marsaglia from California State University, Northridge, has more than 10 IODP expeditions to her credit; she wrote THE compendium and comprehensive atlas of sediments for the entire IODP program. Here she is introducing biogeochemist Martine Buatier from the Université Bourgogne Franche-Comté, in France, to the finer points and the subtle joys of sediment description.

The sediment party is going on all day, and the initial results from this site are already very exciting; sneak previews may be presented tomorrow, slightly veiled and disguised to make sure no sensitive material is published by mistake.

This blog post first appeared on Sep. 27 on my daily blog of EXP385. Make sure to go to expedition385.wordpress.com to read the latest updates of this expedition!