COVID on Deck (Part 1: EXP391)

This post was originally written during Expedition 391, but never published. By the time we made it out of our COVID-19 saga we just wanted to move past the whole thing, and posting this would have forced us to relive the experience. Unfortunately it continues to be relevant, four expeditions later.

The whole world changed

When I interviewed for the position of Onboard Outreach Officer for IODP Expedition 391, I was in the living room* of my Brooklyn apartment. This was not the first remote interview I had ever done, but it was the first time I had to interview in my home because a global pandemic shut down travel and in-person office work. “If you get accepted for this position, you’ll come to College Station, TX in August for training,” they informed me. Then they added, “We hope.”

When I was offered the position, I was told, “We’ll keep you updated.” At that point, I assumed like most people that COVID-19 was a strange blip in my Spring that would be resolved before Summer. I told my boss that I would be on leave from December 2019 to February 2020 and began to make the necessary arrangements.

In the end of June, I received an email informing me that the Expedition 391 COVID-19 protocols had been updated to take preventative measures. Sixteen spaces on the expedition were being cut, and since the science was so important, there would be no room onboard for the outreach position. I was devastated.

What no one expected at the time was that the COVID-19 pandemic would keep getting worse. Eventually, JRSP IODP decided that the whole expedition had to be postponed.

A glimmer of hope

2021 inched by, a year of expectations unfulfilled. Vaccines had given us some hope, but between lack of availability, vaccine resistance, and the rapidly evolving virus, it became clear that we would be living through the pandemic for many months to come.

Yet we marched on, treating Expedition 391 as a fixed point in the future. For me, knowing that I would eventually set sail was the beacon of light helping me navigate through all the other pandemic disappointments. It didn’t even occur to me that 2020 could repeat itself and my position on board could still be at risk until I actually made it to Outreach Officer Training in College Station in August 2021.

The meeting where I was expected to present my education plan to the EPM and two co-chiefs was quickly derailed. “I’m starting to think we should call the whole thing off,” Kaj asserted. He, Will, and Tobias went back and forth over the idea of sailing with a reduced science party, canceling the expedition altogether, or finding some way to proceed as planned. The hour passed quickly, leaving us with less certainty than we started (and no chance to bring up my education plan). All of a sudden there was just as much doubt about our expedition as there had been a year ago.

Yet we marched on, treating Expedition 391 as a fixed but unsteady point in the future. On October 7th, less than two months before the expedition was set to begin, the official announcement came: Expedition 391 was approved to sail with its full science party. The next several weeks were a flurry of activity: flights were booked, hotel quarantine rooms were reserved, and meeting after meeting helped us finalize logistics. Expedition 391 was on!

COPE-ing

In order to ensure the success and safety of our expedition, JRSO IODP developed a protocol to “conduct IODP expeditions on the JOIDES Resolution as safely as possible until we can fully return to normal operations.” Known as COPE (COVID Mitigation Protocols Established for Safe JR Operations), this plan addresses everything from behavior at home prior to travel, to dealing with a potential outbreak on board while at sea.

We were first asked to self-quarantine at least one week (but preferably two) before our flights. For me, that meant forgoing a Thanksgiving surrounded by family I rarely get to see. Instead, I passed the holiday alone at home, eating cold turkey with my dog and my cat.

I then had to scramble to get a COVID test before my flight. If you have not travelled recently, you will not understand the modern stress of a COVID test: the test must be taken within 72 hours of your departure, but most clinics cannot guarantee results in anything under 3-5 days. I spent the next two days frantically refreshing my email, agonizing over morality of digitally manipulating old test results if it came down to it.

Next was the travel. From door to door it ended up being over 24 hours, mask on the entire time, surrounded by people. Airplane seats definitely do not meet the recommendations for social distancing.

A week of isolated quarantine in the hotel was the next hurdle. Luckily our Expedition Project Manager planned so many Zoom meetings for us that it hardly felt like we were trapped in a room – we were too busy to do anything else! With access to the full spread of Cape Town cuisine through Uber Eats, the quarantine could have been way worse.

A subdued start (Out of the frying pan)

In the Before Times, port call was one of the most memorable parts of each expedition. After a twelve hour shift on the ship, everyone would group up and disperse into whichever exotic city was the current location. This is where all the best stories were made: who became best friends (and who didn’t), who got lost and had to creatively find their way back to the ship, who stayed out so late that they made it back just before the gangway was lifted.

But not this time. Once we boarded the ship, we would not be able to set foot anywhere else until the end of the expedition. By stepping onto the gangway, were were committing to sixty days of the JOIDES Resolution being our entire world.

As we settled into our new lives, we lacked the opportunity to bond in the ways that made the start of previous expeditions so rich. We couldn’t sit more than two people at a table during meal times, we couldn’t get together after shift to play games or watch a movie… We didn’t even know for sure what everyone’s face looked like under their masks! We slowly adjusted into our new routines, counting down the days until we could be free of our two-week pandemic prison.

Into the fire

First, it was whispers of one positive case, then two. We made it to our first drilling site, and proceeded as planned. Drillers began to construct the bottom hole assembly, connecting sets of drilling pipe together to make the first trip go faster. The rotary core barrel drill bit hovered just over the rig floor, brand new and glittering in the sun.

Then new whispers started coming around. Five positive cases. Eight. Fifteen.

If it was one person who was sick, or even two, we could have kept going. The problem was that almost an entire department was taken out. All but one of our electricians ended up testing positive. The ship can’t run without electricians. We had to turn back.

Trapped

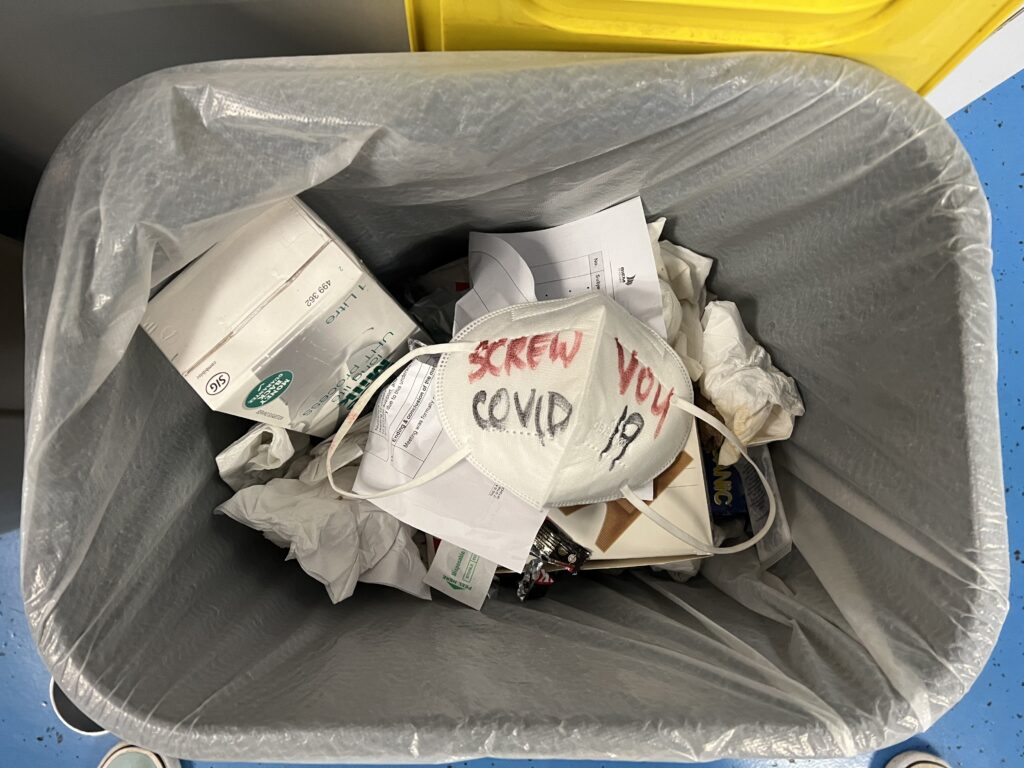

We arrived back in port on December 15th so that the infected members of our party could disembark the ship and convalesce in a hotel. In our labs, we were facing an onslaught of emotion. Fear that we would get sick. Anxiety that the expedition would be canceled after a year of waiting and all the effort of getting to Cape Town, quarantining in isolation for a week, and boarding the ship. Anger that someone had brought COVID on board. Frustration that we didn’t know what would happen.

But we can’t forget that there were members of our team who had it way worse: prior to our return to port, those who tested positive were confined to quarantine in their cabins. Imagine a two-by-three-meter grey box with fluorescent lights and no windows. Imagine being robbed of the opportunity to walk around, to feel sunshine on your skin, to breathe fresh air, for the better part of a week. We scientists thought we had it bad, not knowing what the next day would bring with regards to our science. But several people on the ship had it way worse.

Over the next fourteen days, we languished in port. Every morning we woke up fearing the unknown. Who else had tested positive without us knowing? What sailing decisions had been made behind closed doors? The powers that be had to straddle the line of protecting privacy and limiting speculation, while making sure that we were as informed as we could possibly be.

The days dragged on. At first, it was easy to find enjoyment. As scientists and professionals, we had plenty of work left over from outside the expedition to catch up on, and all of a sudden we were given the gift of days of unstructured time. It was almost nice to have COVID testing scheduled into each day, because it was a mandatory glimpse of freedom from our computer screens.

The days dragged on. We finished our grading, we submitted revisions, put our papers in for review. All that unstructured time was starting to feel less like a blessing and more like a curse. We watched our science slip away like sand between our fingers. It was almost nice to have COVID testing scheduled into each day, because at least it gave us something to do.

Testing, Testing

By December 29th, enough of our quarantined crew had recovered and returned to the the ship that we were finally able to depart. I don’t think any of us were willing to risk feeling hopeful that we would even make it to our first site, let alone collect enough core that we would be able to accomplish the scientific objectives of this expedition.

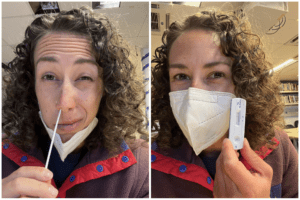

We continued the routine of daily COVID tests, having now experienced them so many times that we graduated to self-administration. We would file into the conference room, each settling into our own corner, and furtively look around while we swizzled the swabs around our nostrils for minutes at a time. We grew used to holding our breath for fifteen minutes, never truly believing the news that we were all clear.

Even as each new day continued to give us negative results, we didn’t dare let ourselves hope that we were out of it. Just one positive test had the potential to undermine the rest of the expedition. But each new day continued to give us negative results. We got closer and closer to freedom.

The future of ocean expeditions

On January 12th, we were finally able to remove our masks and say goodbye to our COVID mitigation protocols. This was the celebration we had been looking forward to for six full weeks. At 13:57 (exactly two weeks after the pilot left our ship in Cape Town, which initiated our “bubble”) we heard the announcement that we were free to inhabit the ship without our masks.

We were giddy.

But even now, we are not free of the experience. We are haunted by the feeling of forgetting something, every single time we walk inside. Our hands still twitch to our pockets each time we enter the hallway or move to a new room, reaching for the ghosts of the masks we thought we said goodbye to. It has been three full weeks and the habit – the fear – is not broken.

And we’re the lucky ones. Outside of our safe little ocean bubble, the world is still being ravaged by COVID-19. Before we even step off the ship we will need to return to our hidden faces and our social distancing: once the pilot steps on board to steep our ship back into port our bubble is officially popped.

Optimistically, Co-chief Scientist Kaj Hoernle pointed out that the implications of our experience extend past just Expedition 391: “This is a very positive sign for marine research globally. It shows that we can successfully carry out expeditions even during a pandemic.” Let’s just hope that this “success” looks a little bit better for the future than it did for us.

*When I say “living room” I mean the one room in my apartment that has a couch and a desk, but also the closet containing all my clothes because my bedroom does not have a closet. This is a Brooklyn apartment, after all.