Routine, Remarkable

I wake up and check my email: a message from a family member, musing, “I imagine it’s all routine at this point.”

Sure. It’s week 7.

Each night, I rise at 10:30, shower, pack my bag with all I need for the next 12 hours, and quietly close my cabin door in case someone is sleeping. I dump my bag in my office and join sleepy night shift folk in the mess. I know their routines now, too: who’ll construct an enviable egg sandwich with the contents of the salad bar, who’ll dip their toast in their coffee, and whose wry wit will start my day with a chuckle. Predictable. Pleasant. Familial, even.

No one else to see. Nowhere else to go. We’re 126 people stuck on a medium-sized ship in the middle of the vast Southern Ocean, after all.

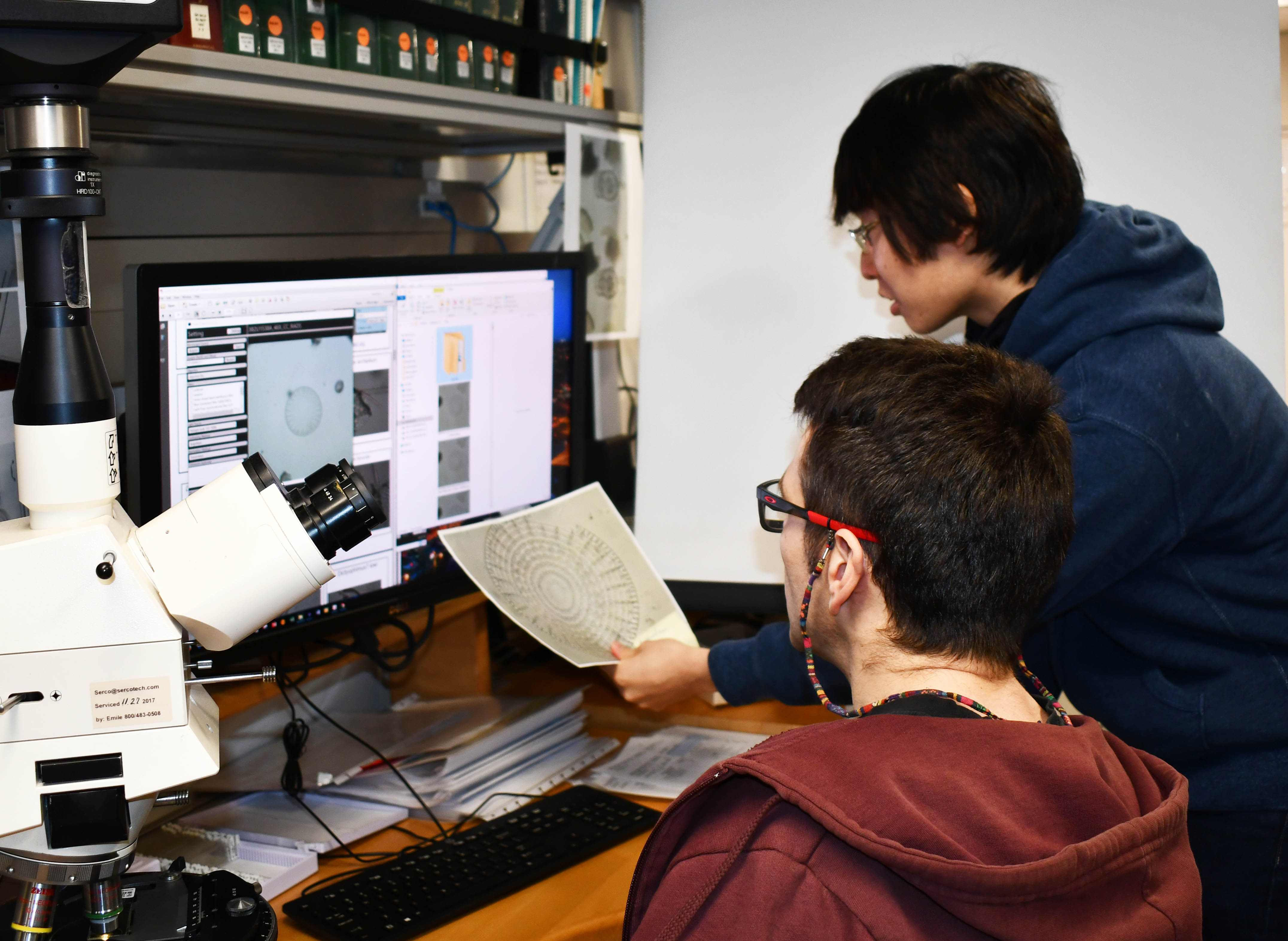

Consider the last 48 hours. As I arrive for work, Thomas thrusts an SEM (scanning electron microscope) image toward me. “Look what the day shift found!!!” he says. I’m left speechless by his animated explanation of just how unexpected this discovery is. Time and again, he beckons me to view rocks forged in Antarctic volcanoes, or layers thick with iceberg-rafted debris that indicate dramatic changes in the Antarctic Ice Sheet over time; each one continues to capture my imagination. I have coffee with Anna and Michelle, sharing their happiness at some news. During live broadcasts to the Philippines, Corsica, Spain, and Brazil, I watch students’ jaws drop as they learn about Antarctica. Yasmina and I collapse with laughter during a series of snafus caused by technology and a roaring gust of Southern Ocean wind. I marvel over fossil diatoms and radiolarians with Iván, Yuji, and Frida. The quiet reverence in Iván’s voice when he tells me, “Sometimes the most valuable things are invisible to your eye,” brings tears to my eyes.

Very soon, we’ll return to our lives on land, Expedition 382 behind us. As time grows short, we seem to be working even harder, drawing closer, laughing more, valuing the experiences that remain. I was unsure how to end these thoughts, but my friend Anna suggested we might flip our perception—that when we return, we might be more aware of smaller remarkable moments—those awe-inspiring icebergs—in our everyday lives back home.

Very soon, we’ll return to our lives on land, Expedition 382 behind us. As time grows short, we seem to be working even harder, drawing closer, laughing more, valuing the experiences that remain. I was unsure how to end these thoughts, but my friend Anna suggested we might flip our perception—that when we return, we might be more aware of smaller remarkable moments—those awe-inspiring icebergs—in our everyday lives back home.

As I write this, Mo walks into the core lab. “Great big iceberg, coming right at us,” she says.

Icebergs, too, have become routine, yet their behavior is unpredictable. While they are inevitable in Iceberg Alley, we never know for sure what path an iceberg will take. They wobble along their routes, slow or speed up, turn back upon themselves. Break up, calving smaller icebergs. Disappear into the fog and reemerge startlingly close. They either force us to move or they drift on by, their presence an apt metaphor for life aboard the JR: familiar but never mundane.