Seriously Hardcore

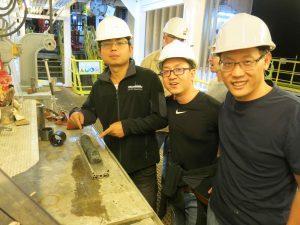

There is no doubt — we are now drilling into the sill. The next core brings an alternating sequence of rocks and hardened sediment, broken into bits but suspiciously looking like the contact interface where the hot magmatic sills have impinged on the cool marine mud into which they inserted themselves. The news means salvation for the hard rock geologists or petrologists; they have now a reasonable prospect of working on something close to their heart instead of being delegated to other groups. Here, petrologists Khogen Singh, Wei Xie, and micropalaeontologist Shijun Jiang are enchanted by a piece of good dolerite sill in the core catcher.

Microbiologists are also quite excited, mostly about the transition from sediment that potentially contains microbes, to rock, which is less likely to contain microbes unless we find a nice fissure or cavity that provides a microbial refuge. The sediment-sill transition interval is treated as if it came from Mars, an extraterrestrial sample prone to contamination by earthlings, and approached only with gloves and breathing masks.

For the last three days, the microbiology and geochemistry groups have discussed an elaborate sampling plan for these critical intervals; there is not much sample material, and whatever there is has to be treated gently and sampled with as much restraint as possible. Here, Yuki and Didi (a.k.a. Diana Bojanova from USC) are cleaning the most substantial chunk of rock with sterile artificial seawater, before X-raying the core samples and looking for interior veins lined with calcite or other microbe-friendly minerals.

An ad-hoc sampling committee convenes on the spot, consisting of myself, co-chief Dan Lizarralde, petrologist Khogen Singh, curator Brittney, and much of the microbiology group as an advisory body. In situations like this, it is important to have all stakeholders in the lab together, to make consensus decisions and to prevent wild sampling that interferes with other interests or even destroys unique samples. Science has changed greatly since the 1830s, when Charles Darwin and a hunting party in the Pampas of Argentina shot a big bird for dinner, realizing much later that they had eaten a previously unknown member of the ostrich family, Rheadarwinii. It is charming to have your mistakes named for you, but it won’t happen here…

Assistant Lab officer Aaron is chiseling some crumbs from a block of hardened, pitch-black sediment, the most extreme sample of what happens to marine sediments when they are pressure-cooked by immediate contact with magma. The crumbs will be checked for residual organic matter and hydrocarbon content.

We expect that the sediment has mostly lost its natural organic carbon content, and the pressure-cooked organic matter was transformed into hydrocarbons and driven out; but some especially recalcitrant types of organic matter and petroleum might still be there. Past events of pressure-cooking large amounts of organic-rich marine sediment appear to have produced shock waves of the greenhouse gas methane, and methane-induced heat waves.

The sampling party continues into the early morning, and by noon another sampling party is starting, this time on the working half of the sill sample from Hole A, now split and laid out in stratigraphic sequence for inspection. Again, the co-chiefs, curator Brittney, project manager Tobias, and interested scientists of mostly hard rock preference — Christophe Galerne, Myriam Kars, microfossil expert Ligia Pérez Cruz, and Louise Koornneef — are present and will mark their sampling spots with small flags.

The hard-rock sampling parties will have lots to do; the sills are coming up and the drilling works really well. Some of the bounty is presented, and it becomes quite clear that the volcanic rock is slowly changing color and consistency with depth. Obtaining a complete section through a sill that has been waiting here undisturbed for 300,000 years, and the carbon cycle story of sill emplacement and hydrocarbon mobilization on top of that, is more or less the dream of this expedition. The hard rock geologists finally forgive the microbiologists and micropaleontologists for the endless diatom oozes (not much better than marine microbial slime) that they had to process as part of the communal shipboard effort.

The day shift technicians and outreach officer Rodrigo are watching rig floor TV, the JR’s live circuit to the rig floor where coring is ongoing, and wait for the next core that can arrive any moment. Keep the rocks coming and life is good again.

This blog post first appeared on Oct. 11 on my daily blog of EXP385. Make sure to go to expedition385.wordpress.com to read the latest updates of this expedition!