So, what exactly is a diatom paleontologist…?

Hi, everyone! I will be sporadically blogging about my time sailing on the Joides Resolution as a diatom paleontologist during Expedition 362: Sumatra Seismogenic Zone. It still amazes me how many exciting things scientists get to do; spending 2 months on a boat in the Indian Ocean might be some people’s idea of a nightmare but I jumped at the chance (Captain Phillips was just a film, we’ll be fine..)! So, to make sure we’re all on the same page to begin with, this first post will be an attempt to explain what I’ll be getting up to during Expedition 362, and what exactly being a diatom paleontologist entails…

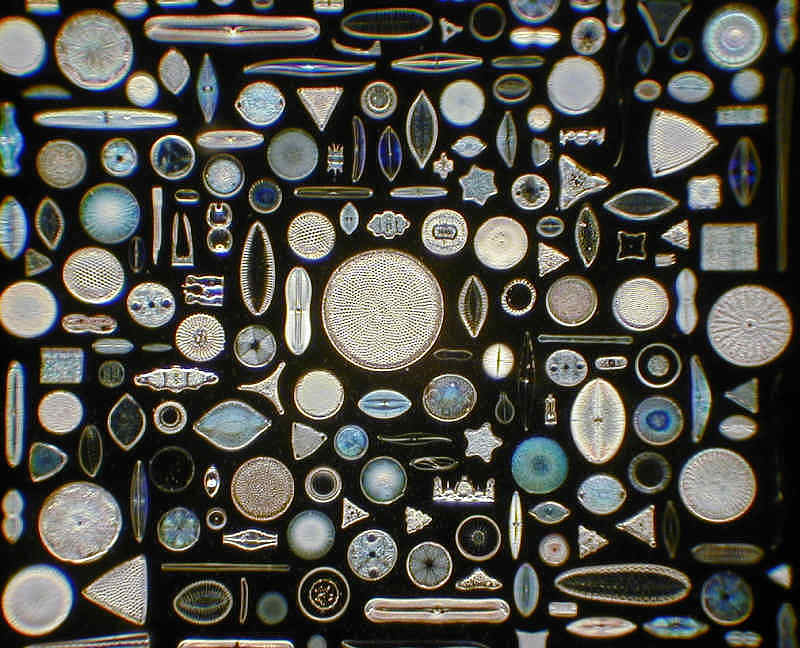

In my experience, the word ‘paleontology’ makes most people think of either dinosaurs or Ross from friends. While I love both dinosaurs and Friends, particularly Sauropods and the one where Joey downs a gallon of milk in 10 seconds, what I do is almost entirely different. I do study fossils, but tiny single-celled microfossils called diatoms, which are even more exciting than dinosaurs. I’m absolutely not biased. Diatoms are a type of algae made from glass that come in a mind-boggling array of shapes and sizes (have a look at the picture accompanying this blog to give you an idea, or just google ‘diatoms’.. I promise you won’t be disappointed!). Basically, they are pretty cool tiny plants that sacrifice themselves at the base of the marine food chain that supports some of the more attention-grabbing ocean creatures such as whales. Diatoms even help us out by slowing down global warming, since they use up a sizeable amount of the CO2 we pump into the atmosphere as a substrate during photosynthesis. They live in almost any kind of water (even tap water!), and can even be used by the police to determine where and when someone drowned!

Earth and marine scientists are particularly interested in diatoms, though, because when they die, many diatoms sink to the ocean floor and become sediment. And because diatom species have been evolving throughout geological history, you can then work out the age of the sediment by identifying the diatoms in it. Knowing the age of different bits of sediment within a sediment core (think ice core, but made of mud), which will also tell you the rate at which sediment accumulated, is really useful- for reasons I will go into in another post! So, during Expedition 362 I will be working with 3 other paleontologists, each studying a different group of marine microfossil- radiolarians, foramninifera and nannofossils to be precise- to bang our heads together and try to work out the age of all the sediment in the sediment cores we collect from the bottom of the Indian Ocean during Expedition 362 . I better leave it there for now, since it’s nearly 3pm and I need to get some sleep before I get up for my next shift (which starts at 11.45pm.. yes, pm!!), but next time I will write another post about which diatoms I have found, and what it all means!

Good luck! The world counts on scientists like you!