The ships that sailed before us

To increase accessibility to our expedition, click to listen to the page text read aloud.

Our departure for South Atlantic Transect I will put us on an exciting journey to learn more about earth processes in the deep ocean. But looking forward to what we may learn and discover is also a time for reflection back to the ocean expeditions that laid the foundation for our work today. There are two specific expeditions we highlight – the first voyage of H.M.S. Challenger, and the third voyage of Glomar Challenger.

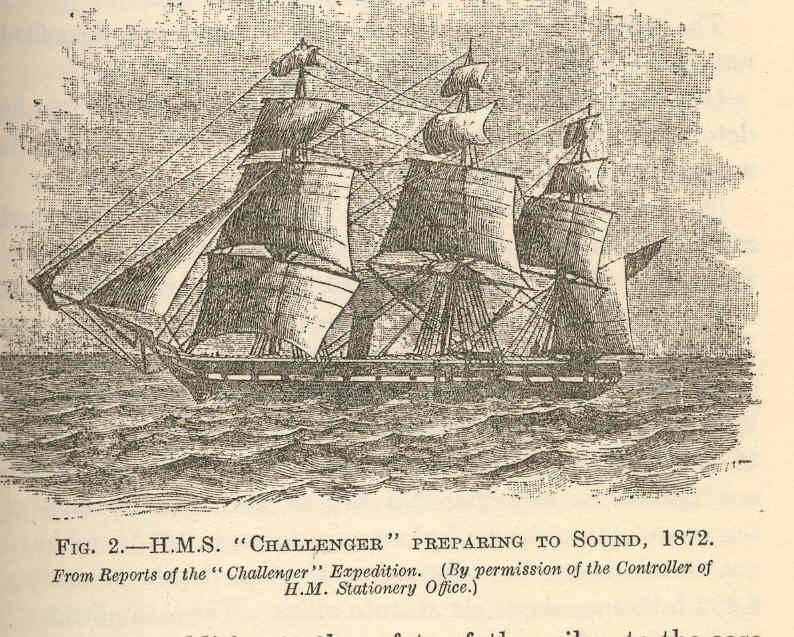

H.M.S. Challenger

From Reports of the ‘Challenger’ Expedition. Image in public domain from Freshwater and Marine Image Bank.

Launched in 1858, H.M.S. Challenger was a small warship with cannons assigned to coastal patrols and to support larger ships in the British naval fleet. The ship was later selected for a multi-year scientific expedition around the globe, departing in December 1872. Alas, the ship was not originally constructed for scientific work, and modifications to Challenger were necessary. To prepare the ship for a scientific mission, necessary adaptations included creating laboratories and accommodations for six civilian scientists to join the 250 British Royal Navy sailors and officers. Although there were several ships that went out on expeditions prior to 1872, the Challenger expedition is the one credited as giving rise to the field of oceanography.

Did you know… John Buchanan, one of the six scientists aboard Challenger and the only physical scientist (a chemist), claimed that oceanography was born “the day the first official observing station of the expedition was occupied, in the Atlantic Ocean west of the island of Tenerife” (Macdougall, 2019, p. xiii). John Murray, another scientist (naturalist) on board, is credited with coining the actual term oceanography (p. 29).

H.M.S. Challenger’s mission was all about collecting samples, whether those samples be seafloor mud, manganese modules, corals, crabs, and plant and animal life from the islands they visited over their three-year journey. The scientists focused on gathering as many samples as possible, then examining, describing, and cataloging what they found.

The six scientists on board Challenger were not concerned about aquatic systems or human/environment interactions – this really was a journey of discovery and documenting what exists in these unexplored regions across the globe. Upon conclusion of the expedition, it took 50 volumes of the Challenger Report to share what was seen and collected – including roughly 4,700 new plant and animal species.

Glomar Challenger and DSDP Leg 3

The Deep Sea Drilling Project (DSDP, 1968–1983) was a 15-year program that explored the sediments on the ocean floor and the upper part of the underlying crust. With the newly-built scientific ocean drilling vessel D/V Glomar Challenger, the DSDP program recovered cores from 624 sites throughout the ocean, providing materials for scientists to study Earth’s deep-ocean environments. DSDP was the first of three international scientific ocean drilling programs that have operated for decades, with JOIDES Resolution as one of the research vessels for today’s International Ocean Discovery Program (IODP).

“Unquestionably … the largest and most successful program of geological investigation ever undertaken by man.” (Emiliani, 1981, p. 1705, referring to DSDP)

Glomar Challenger carried out 96 expeditions, but it is the third expedition (Leg 3, December 1968 to January 1969) that stands out as one of the most significant in scientific ocean drilling history. Leg 3 took place in the equatorial and South Atlantic Ocean, drilling 17 holes at 10 sites. This expedition set out to verify the theories of seafloor spreading and plate tectonics through investigating the tectonic development of the Mid-Atlantic Ridge (the structure and movement of oceanic crust) and examining the history of sedimentation in the South Atlantic Ocean. Scientists were able to confirm these theories and learn much more.

But the South Atlantic Ocean has not been sampled or studied much, compared to other ocean basins. So we are returning to the same region to collect new samples, to perform analyses with new equipment, and to ask new research questions on topics the scientists on Glomar Challenger would never have known to investigate.

It is exciting to sail on JOIDES Resolution during the 150th anniversary year of the H.M.S. Challenger expedition and just over 50 years from when scientists on Glomar Challenger sailed for DSDP Leg 3. And as the scientists, technicians, and crew all waited in our hotel before boarding the JR, a photo taken by one of our scientists was shared across our group. The photo is of JOIDES Resolution approaching the dock, with another ship in port that will go down in history – the SA Agulhas II, which just last month found the location of Sir Ernest Shackleton’s Endurance, preserved at the bottom of Antarctica’s Weddell Sea. We are surrounded by reminders of the historic significance of the sailors and scientists from history, and what we are able to learn and advance for science in the present.

“Without a detailed knowledge of the past, the present cannot be understood and the future cannot be predicted.” (Emiliani, 1981, p. 1705)

References

Emiliani, C. (1981). A new global geology. In: Emiliani, C. (editor). The Oceanic Lithosphere, The Sea, Vol. 7, 1685-1716. ISBN 0471028703

Macdougall, D. (2019). Endless novelties of extraordinary interest: the voyage of H.M.S. Challenger and the birth of modern oceanography. United States: Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-23205-9

I worked with W.Wayne Hollingsworth who was on the 1968 voyage. We were at Intermarine, Houston a logistics company outfitting the Glomar Explorer. 1970-74.