Two observatories give us stereo vision inside the slow slip zone

http://

Click on the location icons to learn more about each site. The Google Map may not work in all web browsers – if you have trouble use Google Chrome.

Two observatories give us stereo vision inside the slow slip zone

Slow slip events are an enigmatic phenomenon, only recently discovered by geologists studying earth’s movement almost twenty years ago. They appear to bridge the gap between typical earthquake behaviour and gradual creeping plate movement.

In the northern Hikurangi region they occur with remarkable regularity: approximately every 2 years, and lasting over a period of 2-3 weeks at shallow depths (<5-15km below the seafloor).

New Zealand’s first observatory, named “Te Matakite” was installed in late March. Now we are embarking on installing a second observatory closer to the east coast of New Zealand.

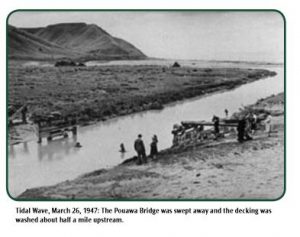

This second subseafloor observatory is also only 20km from the location of a March 1947 earthquake epicentre. This earthquake had low intensity shaking and was hardly felt on land yet caused a 10m local tsunami to hit the East Coast, damaging many roads and bridges. The tsunami affected 120km of coastline, from Tokomaru Bay to Mahia Peninsula.

It still perplexes geologists that the shaking wasn’t felt strongly on land yet there was enough uplift of the seabed near the subduction trench offshore to cause a significant tsunami in this area. Installing another observatory into the slow slip source area above the upper plate boundary might shed some light on how and why this occurred. This will help tsunami evacuation planning for the east coast in the future.

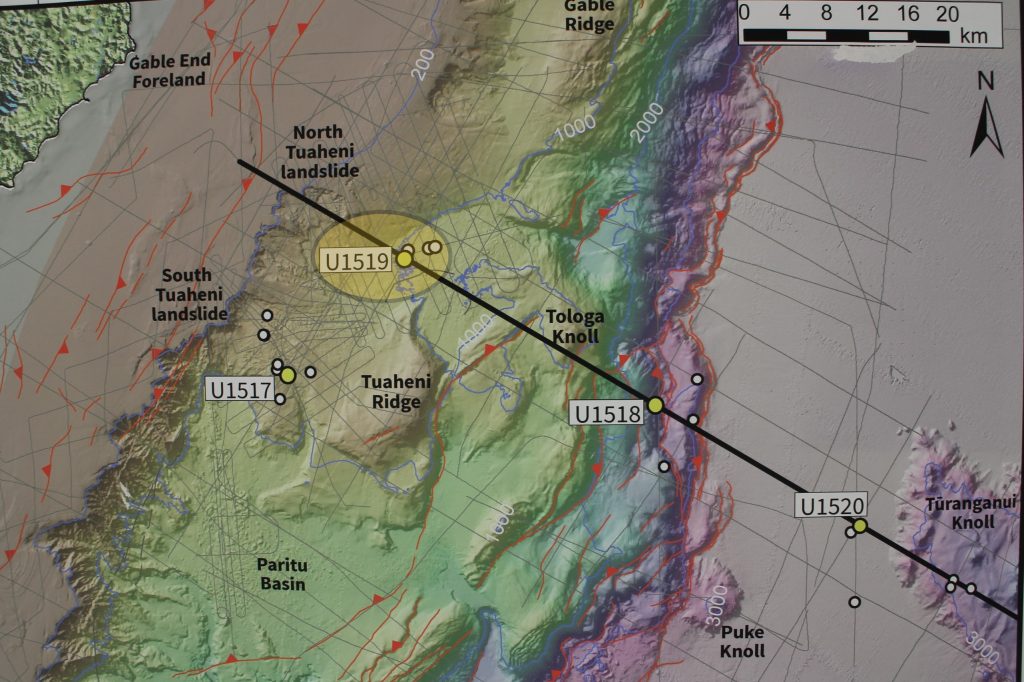

The geology of Site U1519

The location of our second observatory is 33km from the coast and will be embedded in the rock mass of the ‘hanging wall’, with the instruments in the borehole sitting about 5km directly above a known slow slip zone.

This is in an area called the ‘upper slope’ and is mid-slope in a sedimentary basin. It sits quite close to the shallow continental shelf that is attached to the east coast. The water is not so deep here as our previous sites, at 1003 meters.

The observatory has pressure and temperature sensors, so it will help us characterise small movements, as well as the thermal regime and stress conditions of the slow slip event source region, over a long time period. It is not as complicated as the first observatory, however because it is not sitting right in a fault this time. But it will have pressure sensing instruments at 263m and 123 metres below seafloor, and 15 temperature loggers.

There is no other way for us to collect this time series data. Observatories in other subduction zones like this one have shown compression during slow slip events, and then an easing after it as the sediments and rocks below are squeezed, then released.

Stereo Vision

Having two observatories placed at a distance from each other in the slow slip region will enable geologists to see how the two sites behave at the same time before, during and after ‘normal’ (i.e. earthquakes we feel on land) and slow slip earthquakes.

The comparison in temperature and pressure over the same time series will be invaluable, and might show us:

- Do slow slip events propagate (or “migrate”) from this Site U1519 out to U1580, or the opposite?

- Do slow slip events precede or follow larger earthquakes?

- Do they relieve or build up pressure in this region?

- What is the relationship between temperature and pressure changes during earthquakes here?

Unpacking this enigma of these events will help us understand the earthquake and tsunami potential of subduction zone. The measurements of temperature down to almost 300 m in the hanging wall will also provide key information about the temperatures deep below. Ultimately this kind of data will help us understand the “habitat” of these slow slip events, and why they occur in some areas, whereas damaging regular earthquakes occur in others.