Why are drilling expeditions so important?

When you want to study rocks, one of the main complications is to access to them! Most of the time, they are hidden by soil and plants on land and of course, by the water in oceans!

To deal with that problem, geologists have developed indirect ways to image the underlying rocks by using sound waves (called seismic waves) which are generated mechanically. The data collected during these seismic surveys provides accurate information to “see” buried features.

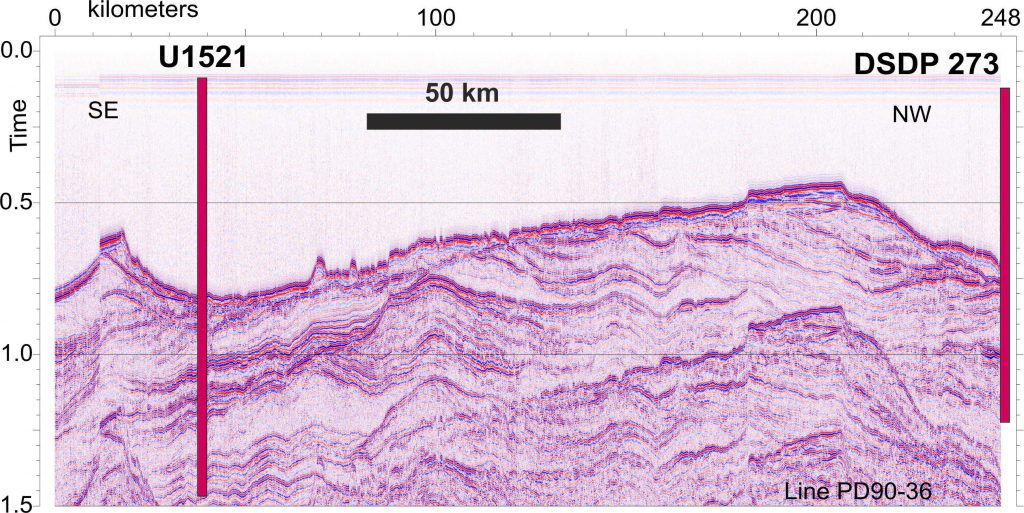

Many seismic surveys have been conducted in the Ross Sea, so scientists already have some idea of the geological history of that region over the last millions of years. The image above is from a US seismic survey that took place in 1990 (Courtesy of Prof. John B. Anderson, Rice University).

What is a seismic survey?

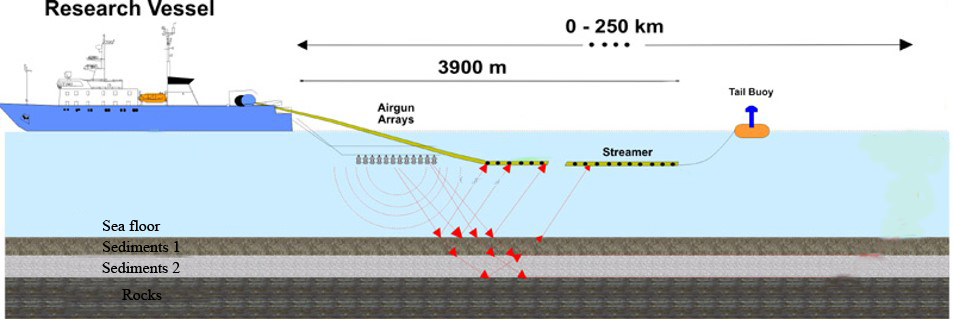

The idea is to use waves which are able to go through the water and the sediments and rock below. A sound wave is created by an “air gun” that is towed from a ship, just below the surface of the water. The acoustic waves travel down through the water and some of them travel into the layers of sediments beneath the sea floor.

When the waves meet a hard surface (the sea bed or a different type of sediment for example), some waves are reflected (which means that they come back toward the sea surface) and only some continue to travel down into the sediments and into the rocks, until they became too weak and the initial seismic energy is dissipated. On the drawing below, only the rays of reflected waves are shown for simplicity.

The reflected waves are recorded by an array of geophones attached to a cable towed by the ship. These arrays are called “streamers” and consist of long net-like bands with hydrophones (sort of like underwater microphones) spaced evenly along the streamer.

An animation is available here.

The information gathered by the geophones are then processed in order to obtain a seismic profile that can be analyzed by geologists.

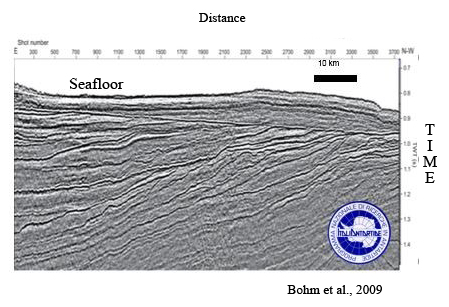

Many seismic surveys have been conducted in the Ross Sea. This is an example of one of the seismic profiles obtained in 2005 under the Italian Antarctic Research Program (PNRA).

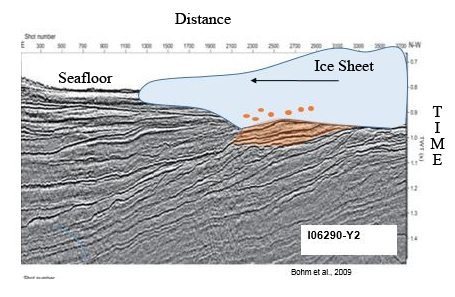

In the example below, we can assume that the orange layer is a sedimentary wedge that has formed below and in front of an ice sheet (represented here in blue) that was grounding on the sea floor, stripping off sediments and entrain them into the basal ice and finally drop them at the ice front.

Why are drilling expeditions so important anyway?

Because even if a seismic profile provides crucial knowledge of large-scale geological structures, it is different from a real geological cross-section in many ways:

– layers in a seismic section are imaging changes in surface reflectivity (eg density change) that are not always caused by a change of lithology, but they may be due to presence of fluid, gas, etc.

– more important, the vertical scale of the image is not the actual depth but it is time (the time corresponding to duration of the travel of the sound waves from the ship to the sediment layers and backward to the geophones)

The results of interpretation of seismic profiles need to be verified with drilling data in order to enhance the accuracy of the interpretation. What make drilling expeditions crucial is that they can provide the missing information needed to have a complete story of the area (real depth, age, rock type [lithology], etc.). But drilling is expensive and time consuming, therefore it is crucial to plan the best site locations by conducting seismic surveys before drilling. Only after having carefully studied the geometry of the strata buried below the sea floor can we confidently drill down to the target. This is also the main technique employed by industry to look for oil and gas reservoirs in hidden “sediment traps”.