Deep in the Hikurangi Subduction Zone

Click on the location icons to read more. The Google Map may not work in all web browsers – if you are having trouble use Google Chrome.

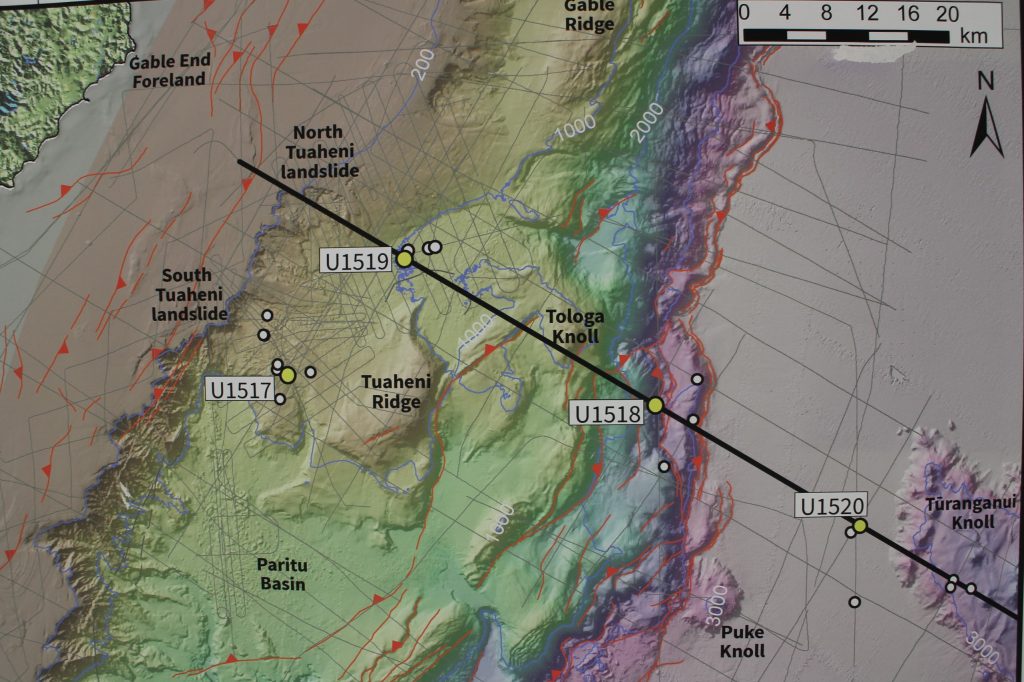

It’s Week 4 and we’re halfway through expedition #375 to study the Hikurangi Subduction Zone. Time is flying! We finished installing New Zealand’s first sub-seafloor observatory (successfully I may add!) a few days ago. Now we’re sitting 90 km east of Gisborne at our second coring site – U1520.

The water depth is 3522 m and is deeper than our first Site (U1518) because we are further out from the coastal platform and in a deep ocean basin.

Our mission here:

On the map here you can see where we are at Site U1520, which sits at the base of Tūranganui Knoll. This knoll has a rounded-top and sits on the margin of the Hikurangi Plateau approximately 100km east south-east of Gisborne. It’s an isolated seamount which rises to 2740m from a depth of 3600m. More on seamounts in our next blog…

We are collecting sediment cores from up to 1050 mbsf deep (mbsf means meters below seafloor), to study the state and composition of the material here. This material is currently part of the Pacific tectonic plate and it will eventually (over millions of years) be carried westward as the Pacific Plate moves into the trench, as if it were on a conveyor belt.

Some of the sediment will be dragged under (subducted) the Australian plate. The rest will be bulldozed and become part of the ‘accretionary’ wedge – this is a mass of sedimentary material scraped off the Pacific oceanic crust during subduction and piled up at the edge of the Australian continental crustal plate. You can see it in the coloured map here as the purple, bluish, and green ‘hillsides’ leading up to U1517.

The geological ‘before and after’

Understanding what this ‘proto’ or ‘input’ sediment is made of and how it behaves BEFORE it is dragged into and above the fault zone means we can compare the two sites. We can conduct experiments on this ‘input’ material by putting it through fluid and pressure tests to mimic what might happen to it as it is transported by the subduction “conveyor belt” deep into the slow slip source area of the fault zone.

We are also measuring and recording its current state (lithology, fossil types, paleomagnetic properties, temperature, porosity, density, shear strength, and chemistry).

All the experiments we are doing now in the JOIDES Resolution labs we will continue and extend back on land. The tests should show us how this ‘input’ material might behave once it is subjected to the forces of the megathrust zone 20km west of here. It might also shed light on why there are slow-slip events in this region too.

Our research questions:

- Are the rocks and sediments here near the seamount unusual? What are they made of?

- Are they dense and compacted out here in the basin at U1520, and do they release fluid as they are heated and buried on the way into the fault zone and slow slip area?

- How does this incoming sediment react when it comes under increasing friction as it nears the subduction zone?

- Will all of it be subducted, or will some be bulldozed onto the hanging wall above?

What are we seeing here in the cores?

The cores we are bringing up are getting progressively older the deeper we get, and we know this from the type of fossils the palaeontologists are seeing under their microscopes – which is no surprise. But what is most noticeable to the untrained eye (i.e., mine) is how hard and brittle this core is compared to our first site above the fault zone.

There the core was quite wet and soft  and it was easy for the scientists to get samples out themselves using small cylinders and tubes. Here the technicians are having to use the circular saw to cut the samples for them.

and it was easy for the scientists to get samples out themselves using small cylinders and tubes. Here the technicians are having to use the circular saw to cut the samples for them.