150,000 Pounds of Stuck

I celebrated the New Year 2022 by accepting a multi-day meditation challenge called Getting Unstuck. Six weeks later, here I am, half a world away from my desk job, floating free on the Southern Ocean.

Presto chango, a bold and dashing adventure!

As you might suspect, it didn’t really happen like that.

I applied to be an onboard outreach officer with the International Ocean Discovery Program more than 2 years ago, just before COVID-19. I then spent 25 months fretting about whether Expedition 392 would happen, and stewing about quitting a steady job for a 2-month stint at sea. Was it wise for an increasingly creaky 62-year-old to set out for such foreign terrain—or lack thereof, as the case may be?

Getting unstuck is a process. Sometimes it goes better/faster than others, a lesson I’m learning in real-time on the JOIDES Resolution.

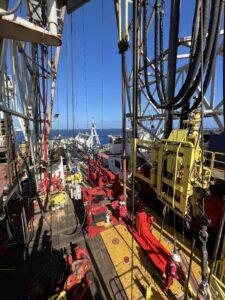

As has been my habit of late, I was hanging out on a deck overlooking the drill floor, mesmerized by the colors and sounds of the hulking, heaving machinery above and below—the collective purpose of which is to drill a hole under the surface of the sea floor and retrieve cores, going deeper with each attempt.

Essentially, in softer sediments the process involves shooting a steel straw into the substrate and pulling it back out when it’s filled with sediment—properly known as piston coring. Imagine shoving a straw through a peanut butter layer cake. When the substrate is sticky or hard, piston coring can become impossible. That’s when we resort to extended core barrel (XCB) rotary coring, which is not unlike corkscrewing into a fine cabernet—if you can envision the corkscrew with a hole in the middle, and the prize being not a sip of wine, but a long, lovely bit of cork.

Essentially, in softer sediments the process involves shooting a steel straw into the substrate and pulling it back out when it’s filled with sediment—properly known as piston coring. Imagine shoving a straw through a peanut butter layer cake. When the substrate is sticky or hard, piston coring can become impossible. That’s when we resort to extended core barrel (XCB) rotary coring, which is not unlike corkscrewing into a fine cabernet—if you can envision the corkscrew with a hole in the middle, and the prize being not a sip of wine, but a long, lovely bit of cork.

At any rate, I was watching while an enviously agile rig floor crew switched the system from piston coring to XCB rotary coring. Coming out of the drill string was a shiny stainless steel half-length advanced piston corer (HLAPC). Going into the hole, a black XCB rotary coring system.

Why make this switch, which eats up valuable hours of the 11 days we plan to be at this particular site? Not because of any trouble shooting the piston into the formation, but rather because of stickiness, according to Bill Rhinehart, who directs the drilling operation. The deeper we drilled, the more challenging it was to pull the core barrel back out. The marshmallowy substrate at shallower depths below the sea floor was now glue-like at 142 meters down.

We hadn’t yet hit rock, so we kept piston coring as long as possible, because the quality of core is so much better versus the more disturbed material recovered during rotary coring, Bill explained. It’s a delicate weighing of risks and benefits.

The upside of piston coring is you get a relatively pristine sample. It has an orientation. Scientists can tell how it was situated in the ground, which is key for magnetic analyses, among other things.

The other day, I was in Bill’s office when we were piston coring the ninth core of the first hole. He kept a wary eye on the number indicating how deep under the sea floor the coring assembly had reached. The number had stayed the same for way too long. It should have been steadily decreasing, indicating all was well with the core’s journey to the surface.

“We may be stuck,” Bill remarked, not seeming alarmed. “It happens.”

What happened next was unusual, however. And unfortunate.

When an assembly gets stuck, the rig floor crew tries to fish it out, essentially drilling over it to wiggle it free. If that fails, the only option is to pull. And then pull harder.

Most often, it pops free. But not always.

“We were 150,000 pounds of stuck,” Bill said, referring to having pulled to the tune of 68 tons—until something broke.

The short, sad story is that the core and core barrel are still down in Hole U1579A, 76 meters below the sea floor.

Since then, having moved just 20 meters to the north, with the JR’s dynamic positioning system holding us steady, we tripped all of the pipe back down to the seafloor to begin Hole U1579B—a 20-plus hour process. Not only expensive and labor intensive, it makes for bleak downtime when scientists are hungry for core.

But soon enough, the welcome words, “Core on deck!”

Getting stuck happens. No one knows with certainty what’s down under the Agulhas Plateau. Expedition 392’s bold and dashing adventure is being the first to venture there.

Fascinating report, Maryalice. I love learning about the rigors of the expedition. Your account has its own factual rigor along with such a compelling and beautifully written narrative style. Can’t wait for your next dispatch.

Holy moly that all sounds so exciting. To be part of this adventure is such a privilege. I’m proud of you and happy you are there enjoying it. It’s flying by so soak it all in. The sea, the air, the light, the wind. Miss you and love you