You have to go where to get microbes?

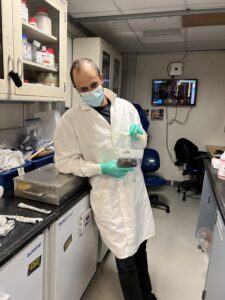

When I first got invited to be the Outreach Officer for Expedition 393 back in May, I was ecstatic. At the same time, I was curious about what I would learn because geology is a completely new field of science to me. I have learned a lot about how research is done on the JOIDES Resolution (JR), but what stands out to me the most is the fact that we have microbiologists on the ship. The proposal for this scientific ocean drilling research project included microbiology amongst other disciplines of geosciences. From the very beginning of the expedition, every time we get ‘core on deck’, we have to wear masks, gloves, and spray everything with alcohol to make sure that we reduce as much contamination as possible, so we can record the types and amounts of microbes that exist in the sediments and rocks. Therefore, any microbes found in the samples provide evidence for what kind of microbial life exists in the seafloor and underneath in the oceanic crust. I thought it was interesting to have a microbiological focus among the amazing and very interdisciplinary research on the ship that allows for the greatest collaborations and discoveries.

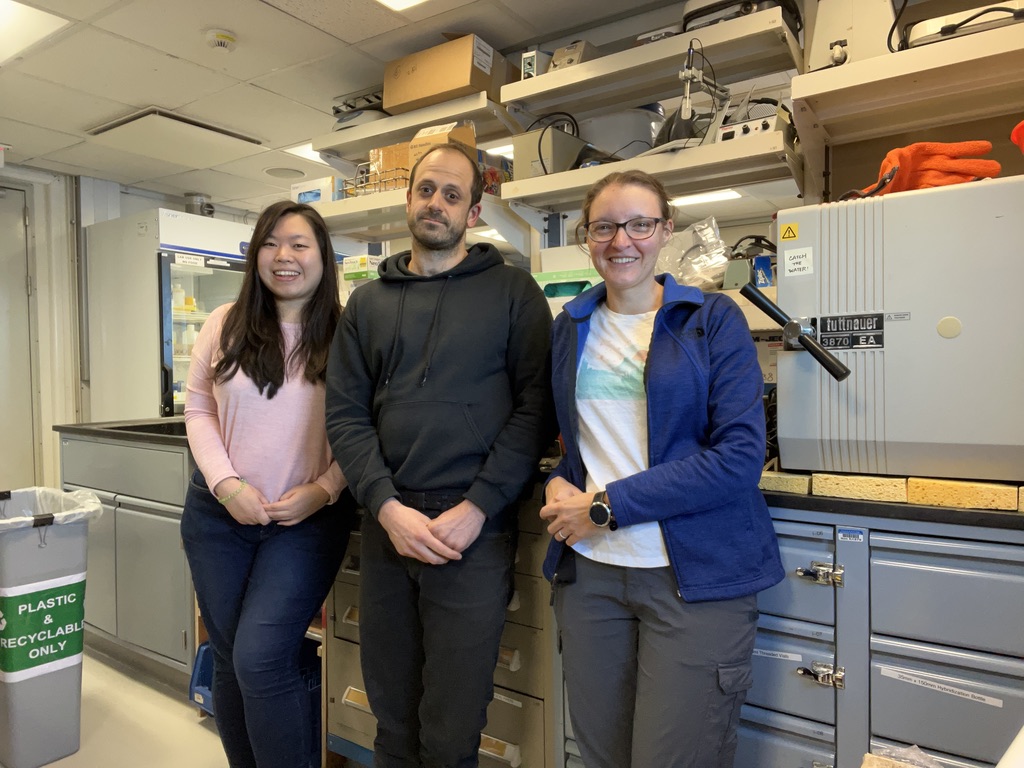

The other day I asked the microbiologists on board what interested them about studying microbes out at sea. Below are their responses.

Jessica Labonte:

I think microbes living in the biosphere are fascinating, yet we do not know that much about them. There may be as many microbes, in terms of number, in the subsurface than there are in the water column, yet we don’t know about their contribution to the global geochemical cycles of carbon, nitrogen, and other nutrients.

Studying the biosphere can inform us on many aspects of life. How do microbes grow and survive under extreme limitation? Some subsurface environments are analogs to other planets, so studying them can inform us about how extraterrestrial life could be. The discovery of novel microorganisms can also inform about the origin and evolution of life, as well as the discovery of novel antibiotic compounds, or new metabolic pathways.

As for my personal research, we know so little about viruses in the sediment (and absolutely nothing in the basement) and it is an unexplored aspect that needs further investigation. We know how many viruses on average are found in sediment, but we know very little about which microbes they infect and the impact of viral infections on the environment, which could be about nutrient recycling, horizontal gene transfer, or other mechanisms we aren’t aware of. We also do not know much about who they are either.

Shu Ying Wee:

Hi! I’m Ying and I’m a microbiologist who studies rock samples retrieved at and below the seafloor. Looking at rocks, it is not always intuitive to humans that life can be present AND survive (maybe even thrive) in there. However, life finds a way to persist. I am in this field of extreme microbiology because I am interested in solving clues about their resilience and survival in conditions that we typically would find hostile. I am curious about who’s there, what they are doing or have done, and how we can apply this knowledge to answering questions about global biogeochemical cycles, Earth’s history, and advancing biotechnology. Investigating these environments also provide insight into life potentially present on other ocean-bearing moons or planets such as Enceladus and Europa, where an ocean sits atop a rocky core. We can therefore learn about similar environments in our solar system that we do not yet have the capability to access. It’s a hard rock life but I am here for it!

Timothy D’angelo:

By volume the oceanic crust is a larger habitat on Earth than what? because most of our planet is ocean. There are very low amounts of cells per cubic centimeter in the ocean though, compared to the hundreds of millions you can find soil and other surface areas. There have been a handful of papers regarding the functions of what they perform and only about 20 years of research so far. It is interesting to learn more about why there is that difference in abundance. Bacteria live in ocean crust and we already know that because we have found them in several places. Then it is also interesting to learn about what functions they are performing in biogeochemical cycling. Plus, there are more basic questions of how does life exists at such low nutrient environments. Then there is research on exobiology, for example whether there are bacteria, or something like bacteria, living on other planets. Crustal biospheres would be the most similar thing on Earth. So, trying to understand how they are living at the seafloor would give us that insight.

The research is much slower than other fields of microbiology because you have to get enough funding to go on a ship to do research, and then you have to do several steps to get your samples and preserve the samples while on the ship. You cannot do experiments on the ship as easily as you can somewhere else in laboratories. Long term studies are few in numbers so far. Thus, the next step is to figure out what bacteria are doing in the giant circuit of biogeochemical cycling, and what they are contributing to. So, coming out here will add to the growing knowledge of what life is like at the bottom of the ocean, what they are doing, what is the extent of the microbes influence in the ocean crust. Plenty of laboratory studies show that bacteria are playing a role in geological cycling (oxidizing minerals, reducing minerals, scavenging minerals). But understanding what is going on in situ is more challenging, and equally interesting. I was attracted to the novelty of doing research in oceanic crust because of how few studies there are, and to learn how life can live in such extreme areas while playing a large role in biogeochemical cycling.