A Foram Fairy Tale

Once upon a time, on a faraway sea, Ashley Burkett was renowned for her fondness of foraminifera.

Also known as forams, these single-celled marine organisms are much beloved by micropaleontologists for their enigmatic beauty as well as for the clues they give about Earth’s history. Forams yield spectacular fossil records, reaching back hundreds of millions of years. The presence and the absence of various species in sediment samples tell time, in a geological sense.

The accurate dating of the cores we recover is key to Expedition 392’s mission to reconstruct the evolution of the Agulhas Plateau. This makes Ashley’s penchant—putting names to the faces of forams—quite priceless.

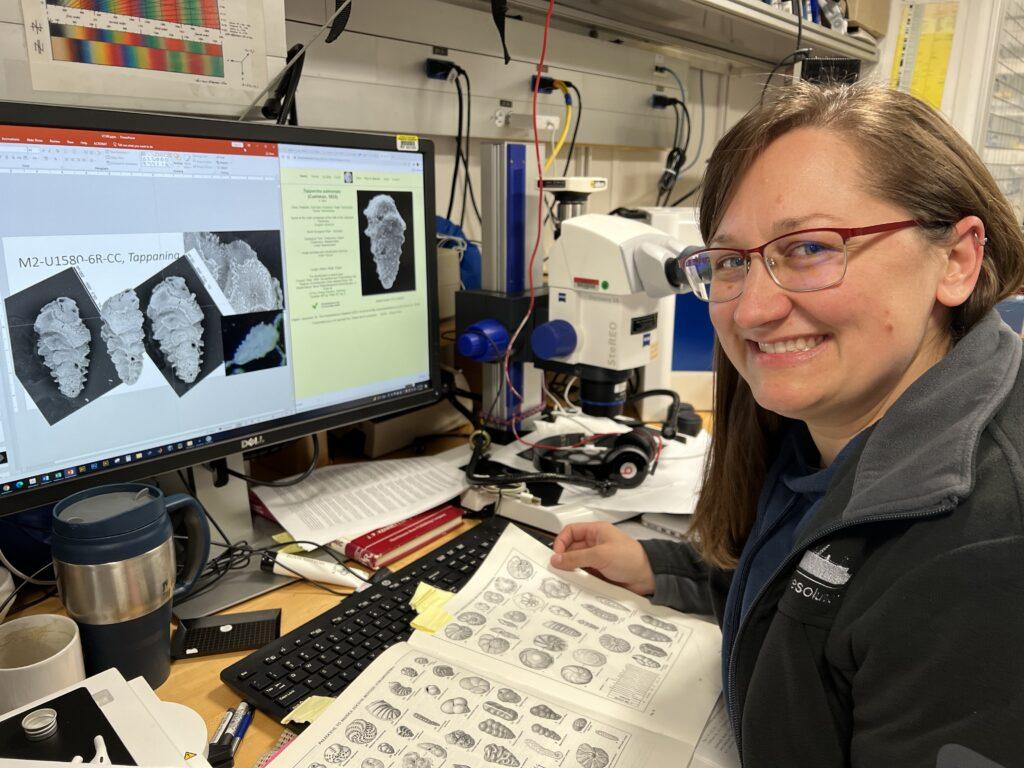

Recognizing forams—which measure no larger than a coarse grain of sand—is an art and a science requiring that Ashley peer at them for many hours through a microscope. This feat, performed while riding the swells of the southwestern Indian Ocean, requires bravery, if not safety glasses.

Ashley is not alone on her quest. She has micropal counterparts on the JR who study dinocysts, diatoms and nannofossils. Their collective purpose is to corroborate findings, about not only abundance or lack of fossil groups, but also, notably, the originations and extinctions of species in the cores as we drill back through various ‘cenes (ie, Miocene, Paleocene) and into the Cretaceous. Because their task is so important, they get first dibs whenever a core comes on deck, each laying claim to a bit of sediment from the aptly named “core catcher,” which contains the very bottom bit of sediment recovered.

Micrometer-sized nannofossils are, by far, the most abundant group of organisms that team micropal sees. When smeared on a glass slide and viewed under a microscope, a single speck of whitish sediment contains thousands of nannos, all looking like the Milky Way on a clear night.

Forams are orders of magnitude larger than nannos, which entitles Ashley to a bigger piece of the core catcher pie. After patiently washing and cheerfully sieving each sample, she eventually amasses enough grains of fossil to cover the bottom of a tiny glass tube.

Then the challenge begins: identifying each species of the hundreds of forams that she encounters.

Despite devotion to this task, Ashley found herself outfoxed last eve. A particularly wily foram eluded identification throughout the dark, lonely hours of the midnight shift.

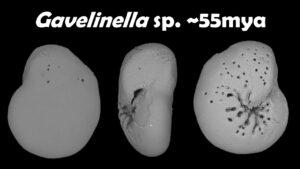

She noted its spiral shape, and identified it as a benthic, meaning it once lived in the sediments of the seafloor. One of the oldest groups of deep-sea organisms, benthic forams trace back to 1150-690 million years.

When viewed under the binocular light microscope, the twisty little creature made Ashley’s head spin. It looked so different from the image of it rendered by the scanning electron microscope, which revealed ridges on its surface.

How curious. Clearly it was not who she initially thought it to be.

She assessed aperture—the placement and shape of the hole through its outer body, which is known as a test. Foram tissue—not preserved in the fossil material she was looking at—consists of a single cell with an anastomosing pseudopodia—which basically means it can do amazing things to catch and gather food.

She checked chambers, noting the number and shape of those making up the test. Forams grow incrementally by adding new, slightly larger chambers.

She scrutinized sutures—where each chamber is stitched together.

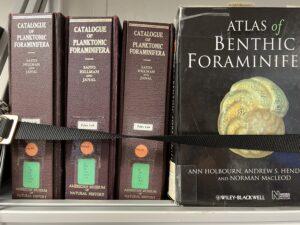

Thoroughly perplexed, Ashley flipped back and forth through a worn atlas of forams, surveying the defining features of spiral-shaped benthics that had lived and died through the ages. The fact that her foram hailed from a high latitude complicated the matter, as major gaps exist in fossil records for locales such as the Agulhas Plateau.

Best to sleep on it, she concluded, as her 12-hour shift wound down.

That’s when things got even curiouser.

The long-dead creature stalked Ashley. It slipped into her sleep, teased her subconscious.

Suddenly, she sensed who it was. Mystery solved!

She woke feeling clear-headed and victorious, certain she’d pinned down her foram . . .

But . . . no.

Slowly realizing that what had seemed so real was all just a dream, Ashley strode straightaway from stateroom to scope. She eyed her foe with a vengeance. She would not be fooled again!

After considerable toil and no small amount of cunning, she declared it a Gavelinella, which lived about 56 million years ago. This unfortunate benthic foram, or more likely its descendants, experienced the Paleocene-Eocene Thermal Maximum (PETM) when, within a few thousand years, global temperatures spiked, ocean chemistry changed and oxygen likely decreased.

The PETM—its cause still under investigation—was a crummy time to be a benthic foram. In fact, this intense climate event wreaked havoc on life far and wide, essentially wiping out up to half of all benthic species.

As the JR sailed majestically into the sunset, Ashley had to wonder: Was the foram’s phantasmic visit about unfinished business related to its demise?

Ashley lived happily ever after. (The Gavelinella, of course, did not.)

The End