A rock is a rock is it not?

I have had the privilege to sail twice on the JOIDES Resolution, with this being my second cruise, Expedition 402 Tyrrhenian Continent-Ocean Transition. The first time was with Expedition 393: South Atlantic Transect II. We aimed to study the age of the oceanic crust as we moved away from the mid-Atlantic ridge toward South America. You can see the expedition summary here.

At the time I had very little understanding of rocks and sediment besides what my oceanography class in college provided me. Most of my academic career was focused on the biology of organisms, so when I thought of rocks I thought of how they provided shelter and structure for the living things that I studied. For instance, rocks provided a hard surface for corals and algae to root themselves and sediment provided hiding spots for bottom dwelling fish. After a few days on Expedition 393, I learned that rocks and sediment can hold the history of our atmosphere, the history of our oceans, and the history of catastrophic events (big or small).

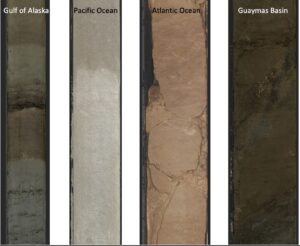

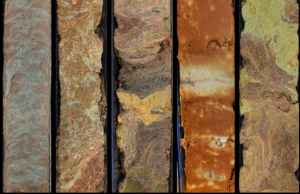

The rocks and sediment on both expeditions have been extraordinarily different. I cannot say that I have seen a similar core between the two, which makes sense because we are in drastically different areas. But again, I had the genuine thought, what could be different about the seafloor from one place to another.

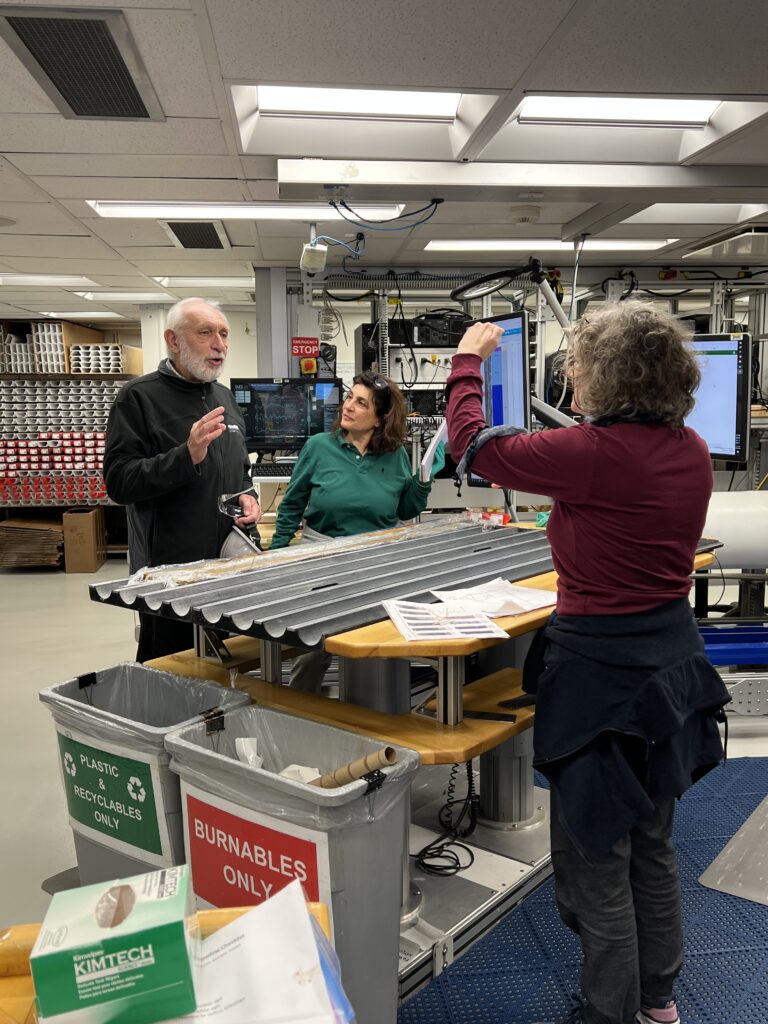

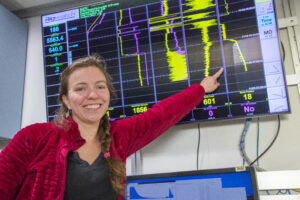

Each expedition has different goals, and different operation expectations, however the methods we use to drill, make thin sections, make p-wave velocity measurements, and more tends to be relatively the same give or take some modifications. For example, thin sections can only be done by taking a small piece of hard rock, cut a thing slice from the top, then polish it down to the thickness of a hair strand. That process does not change because we found a rock in a different ocean. As someone who was returning to the JOIDES Resolution, I envisioned seeing similar gray rocks with some dark grays and browns, I envisioned seeing sediment that followed the color range of chocolates in a chocolatier shop. I figured I was going to be learning about the ocean floor from a different perspective guided by the different expedition objectives. Immediately, I was very wrong and it was thrilling. As Phillipe Pezard, our Downhole specialist, said on one of our first days: “I am a kid in a candy shop”. The ship is a candy shop and the scientists are the local kids who just got their weekly allowance.

Sediment in the Tyrrhenian Sea did not look the same as that of in the South Atlantic, nor did it seem to act the same way when we drilled into the seafloor in both locations.

As someone who does not immerse themselves in geology every day, I still was able to follow the science party as they explained their research goals and expectations from the scientific prospectus in the weeks leading up to expedition 402. Rationally it felt straightforward to understand that under different circumstances like temperature and pressure sediment and rocks react in certain ways. It felt straightforward to understand that these materials will undergo change, erosion, weathering, layering and more. But once I saw the actual cores a foot away from my face, it was a whole other beast. That is the value of field work and that is the value of this ship. You cannot learn more about this planet if you do not have access to it.

As I reflected on my two expedition experiences and saw the science crew experience a range of emotions as new cores were collected, I decided to go around and ask some people who have been on multiple expeditions for their perspectives.

“What has surprised you about the rocks and sediment you have seen across expeditions?”

Alejandro has sailed on 8 expeditions (or 6, he wasn’t entirely sure) and is sailing as the Physical Properties Lab Specialist. He is most surprised by the homogeneity (the sameness) and the gradual change in characteristics of the cores from the bigger oceans. When he was in the Pacific it took a few cores before you started to see a huge color change or texture change, while in the shallower basins the cores tend to be more heterogenous (varied) and have more rapid changes to their features. It always keeps him asking why.

Emily Estes has sailed on 4 expeditions with the JOIDES Resolution and is the current Expedition Project Manager. She is surprised that even when we have the prospectus identifying everything that we expect and understand to be in the area, we still find something different. Especially when the data in the prospectus is based on previous drilling sites in the area, one would think the core would bring few surprises. Though she does not think of these moments as bad surprises, but as opportunities to ask more questions. Most of her work and expeditions have been in larger oceanic basins where there are similar features throughout multiple cores before it starts to change, which is not the case for the shallower basins like the Tyrrhenian Sea.

Kevin Grigar has sailed on 24 expeditions and is the Operations Superintendent. Though his role is to check how well the cores are coming out to help determine with SIEM Offshore what could change about the drilling operations and procedures, he still gives the cores a look. What surprises him is the change in formations and color throughout the cores, sometimes within the same core and sometimes it is after a few ones. Either way he is amazed, and loves how pretty the changes can look.

James Kowalski has sailed on 3 expeditions and is sailing as the ship curator. He is surprised by the laminations (layering that happens in sedimentary rocks) and features that disappear quickly between cores. He finds that each core is so different and rarely sees similarity across expeditions. The variety is something that he enjoys and it keeps him on his toes.

Hearing their responses made me think of the cycle of scientific thinking (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=j12BBcKSgEQ) and what one of our co-chiefs, Nevio Zitellini, said the other day “We start this expedition with a question, and we end this expedition with more questions.”

As we settle into week 3 of Expedition 402, I enter it even more consumed by two notions. First, that we still have so much to learn, and secondly, it seems that when I ask “how could rocks and sediment from one ocean to another be different” it is a question that scientists and the public, alike, share.

Wonderful article and observations, Tessa!

This is so cool Tessa! Your article left me wondering what is a p-wave ? What is the difference between a geologist and a petrologist? What does a curator do ? Not to mention leaving me curious about theories and conclusions this exploration will bring! Thanks for writing about your experiences…curiosity and wonder are such a great experience.