Collaboration from Pole to Pole

One of my favorite activities aboard the JOIDES Resolution is wandering about the core lab, learning from the scientists at work. Today, I chatted with early career Paleomagnetist Brendan Reilly and PhD candidate Sedimentologist Anna Glüder, who are both based at Oregon State University. This is Brendan’s second time in the Antarctic and Anna’s first, but it’s their third research cruise together. I was curious about how their skills and interests complement each other’s.

Ice sheets and glaciers around the world are melting and contributing to sea level rise, and the Greenland Ice Sheet and specifically the massive Antarctic Ice Sheet are of most concern. But we still don’t know how much and how fast the ice will melt, nor which processes in the climate system they are most sensitive to. This is especially true for marine-based ice sheets, those that sit below sea level, which may be vulnerable not only to changes within the atmosphere but also to warming ocean waters wearing on them from below. The long sediment record we’ll recover by drilling hundreds of meters into the seafloor during Expedition 382 will extend our understanding of the Antarctic Ice Sheet on million-year and longer timescales.

“There are slow, gradual changes. And then in the geologic history, we see a lot of evidence for these fast, rapid changes. When we’re thinking how sea level will change in the next 100 years, it’s difficult to say what exactly will happen. We don’t fully understand how fast changes can occur or the processes that drive them and limit them. So, when we study these past glacial systems from different perspectives, maybe I see the response of the glacier, and Anna can determine which forces are involved in driving these changes.”

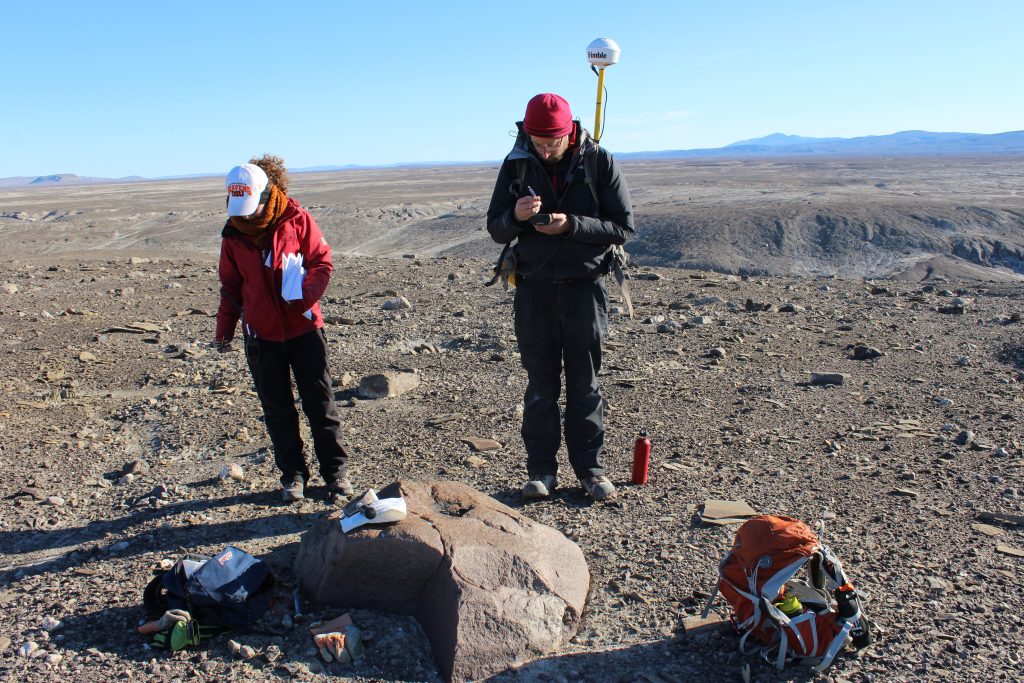

In their previous work in Greenland, they looked at the Petermann Glacier, which—unlike some of the other glaciers that drain into the sea—has been relatively stable over the last century. “We wanted to learn if it has always been that way,” says Brendan. “And if it hasn’t, what oceanographic or atmospheric conditions have driven dynamic changes in the past.”

While Brendan studied the glacial sediment deposits, Anna looked at shells and their distribution. “Near the edges of the large ice-sheets, the local sea level was a lot higher during the last ice age,” she says. “The weight of the ice sheet pushed the land down, but then when the ice melted, the land rebounded to its former position. Land that was previously below water rose above sea level. We can still see evidence of this in the shells left behind in areas that are now up to 130 meters above sea level. I collected shells at various elevations. When you date them, you get a really nice curve of where sea level really was at what times. Using these we can test some ideas on whether the changes in ice extent Brendan is seeing in the Petermann Fjord are linked to changes in sea level. ”

During Expedition 382, like everyone else aboard, they are working with the sediment cores we’re retrieving.

“I’m describing the sediment we get,” says Anna. “I look at the color changes and the lithology changes—how big or small the grain size—throughout each core and describe the different types of minerals and microfossils we find.

Brendan is determining the age of the material. “I’ll be able to tell the science party, ‘This core is roughly this old.’ Hopefully, eventually, we’ll get a more detailed record of the chronology that will show the rates at which things are changing and how the changes we see here correspond to the changes we see elsewhere.”

I ask them each what they like most about this opportunity.

“I love the feeling of pulling up cores and really getting to know interesting scientist people. You’re not just learning something new every day, you’re changing the way you think about your science every single day.”

“I love how much you learn,” agrees Anna. “You have so many experts around you who love talking about their fields of interest. You never get that much concentrated science that’s focused on the same thing.”

It’s a common feeling among us all on Expedition 382: a sense of shared purpose and knowledge, true teamwork as we all work together to advance our understanding of the history of Antarctic melting.

“And even though the Antarctic and Greenland Ice Sheets are on opposite sides of the planet, we can’t look at these regions as isolated cases,” says Brendan.

Anna agrees, “We have seen in the past that the world is responding to change as an interlinked system, and we can see and understand the links between them by comparing the timeline of events archived in the sediment cores from one pole to the other.”

As I think about this conversation now, I truly hope that as their careers continue, these two young scientists continue to work together from pole to pole. I’m eager to know what they’ll discover!