COVID on Deck (Part 3: It happened to me)

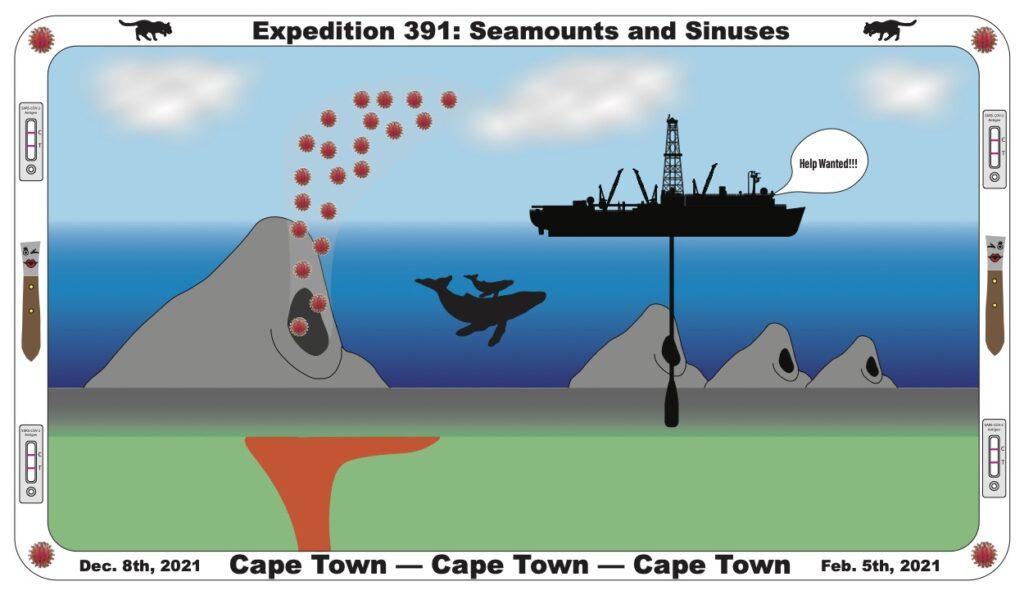

Featured image designed by EXP391 scientist Jesse Scholpp.

Disclaimer: The views expressed in this post are not representative of the International Ocean Discovery Program, the US Science Support Program, the National Science Foundation, or any other organization involved in the operation of the JOIDES Resolution.

On Sunday, September 18th, President Biden declared the COVID-19 pandemic “over” in the United States. What???

Now, I know I’m not technically in the United States. I’m in a beige box with fluorescent lights and no windows, floating in the middle of the south Atlantic Ocean. I’ve been here, in this room, for ten days. From where I’m sitting, the pandemic certainly is not over.

As we all know too well by now, COVID-19 fully inserted itself into the USA in the early months of 2020. The last “normal” IODP expedition on the JR ended with EXP378 on February 6th, and from then on it was eighteen long months of tie-ups and engineering operations, impossible to operate a scientific ocean-drilling vessel as usual while still maintaining pandemic safety.

Despite this, IODP persevered, and the end result was a fairly productive couple of years for the JOIDES Resolution. You can learn more about how IODP dealt with the challenging task of operating during a pandemic in COVID on Deck: Part 2, written by IODP Manager of Science Operations, Dr. Katerina Petronotis.

• • •

After a year of postponement, Expedition 391 marked just the second time that IODP would attempt to sail with a science party “as normal” (Read COVID on Deck: Part 1 to see how that went), though seven scientists were unable to sail due to the pandemic. Even still, this new normal meant a week of self-enforced quarantine at home prior to traveling, then another week of IODP-enforced quarantine in a hotel room in Cape Town. Despite these measures, COVID still found its way on board and decimated the operational plan.

At least it was a learning experience. With Expedition 392 came the introduction of daily rapid tests to try to catch the virus before it made its way around the ship. This change seemed to work. First Expedition 392 made it port to port with no outbreak, then Expedition 390, then Expedition 393. Did IODP figure out how to eradicate COVID from ocean drilling once and for all?

Given these three successes in a row, it made sense to consider relaxing COVID mitigation protocols. Seven days of quarantine prior to a sixty day expedition was taking a toll on IODP, Siem, and Entier staff, robbing them of a full week of time that should rightfully be spent at home with loved ones. Not to mention the cost. All of a sudden IODP had to budget in seven days of hotel rooms and per diem rates for over a hundred people. Even in the grand budget of operating a drilling ship this addition was far from negligible.

Expedition 397P, a tie-up in port, was the turning point. The powers that be decided the seven-day hotel quarantine could be reduced to four days, though daily testing would continue. This change did wonders for the mental wellbeing of everyone scheduled to sail, but unfortunately was not sufficient to prevent an outbreak on board. Over the course of the 34 day tie-up, 18 people caught the virus (not counting the nine who tested positive prior to travel, and the two who tested positive in the hotel). Unfortunately with contractors coming on and off the ship on a daily basis, it was impossible to tell if this new outbreak was the result of the decreased quarantine, or increased leniency in terms of who was allowed on board for imperative renovations.

Expedition 397T went forward with the reduced quarantine as planned. Four days alone in the hotel passed much more quickly than expected. I felt like I still needed more time to fully explore the world of Cape Town Uber Eats, and befriend the people I could see in the windows across the hotel patio. I didn’t even get a chance to take my embroidery hoop out of my suitcase (though that’s probably for the best. I’m not very good). I had been looking forward to four days in isolation* as an opportunity to catch up on work and recharge my introvert battery pack, but before I knew it it was over. Oh well. Onto the real adventure.

Transition to the ship passed smoothly enough. I think everyone felt confident about COVID. The nurses tested us by swabbing our tongues and then using the same swab to probe our noses, so that had to be a thorough test, right? At least they didn’t do it in the opposite order.

September 10 began our series of daily tests on the ship. Day 1 was all clear, with a collective sigh of relief throughout the ship. The science party in particular was thrilled to get the “all clear” because we are still living with the memories of Expedition 391.

Day 2 was not so lucky. One scientist woke up with a sore throat and congestion, and tested positive that morning. She was quickly whisked away to a quarantine room, away from shared hallways and bathrooms. Thanks to how proactive she was with noticing her symptoms informing all necessary parties, she was able to avoid interacting with anyone as an active COVID case.

Day 3 passed with no new positive tests, again leading to sighs of relief across the board. We had all been so good about wearing our masks inside and around other people, so it looked like we effectively prevented the spread.

• • •

That’s when I got the chills. I tossed and turned all night, freezing and unable to sleep, desperately telling myself it wasn’t COVID. It couldn’t be COVID. I made it through the entire pandemic without catching it once… How could I get it now? But when my alarm went off the next morning I knew. I emailed the Expedition Project Manager and soon enough the doctor was knocking on my door to give me a COVID test.

Fifteen minutes dragged on.

The doctor came back.

Positive.

Devastating.

He said, “This, your first positive test, is Day 0. On Day 5 I’ll give you another test, and then every day from then on. You need to get two negative tests in a row before you can get out of isolation.” He smiled and bounced back and forth on the balls on your feet. “Good bye!” he said. “Let us know if you need anything!”

No five days have ever passed more slowly in my life. What can you do when you’re trapped in a cabin on a ship with no opportunity to socialize, breathe fresh air, or see the light of day?

-

- Pace. I maxed out at 13,744 steps, which in my room was 5.1 miles, and approximately a hundred million laps.

- Watch TV. I alternated between the local channel that showed everything I was missing on the drill floor, and the channel that seemed to be showing every episode of every show ever made by Sir David Attenborough. Did you know that bees buzz at a different frequency when they get near flowers to vibrate the pollen off?

- Dry brushing. There is no solid body of scientific research to demonstrate that this does anything (read: PSEUDOSCIENCE) but when you have been alone with no new stimulus for ten days, rubbing something scratchy all over your skin is life-changing.

- Clean out your email and downloads folder. I used to be one of those “6000 unread emails” people, but now I am a “22 unread emails” person, and that’s just because those 22 emails contain links to YouTube videos that I can’t load on the ship.

- Attempt embroidery. I’d post a picture, but the words that I stitched and decorated with dainty (and sloppy) flowers are not appropriate for an educational website.

- Get creative with time. I tried to see how long I could take to eat a single meal. Just to make the time go by. This worked even after I lost my senses of smell and taste. Another scientist in isolation would have solo dance parties.

- Create a “smell obstacle course” to try to identify the exact moment when your sense of smell comes back (it didn’t for me). Hand sanitizer. Deodorant. Lotion. Vitamins. Tea bag. Poo pourri. Repeat.

- Freak out about the split ends that you can’t do anything about.

- Cry. I don’t want to say anymore about this one.

- Definitely do not look at yourself in the mirror.

The first thing that broke me was finding out that my COVID test was scheduled for Sunday, not Saturday like I thought. It is cruel and unusual to refer to the first day of quarantine as Day 0, because it means that you have to wait six days to bid for your freedom instead of the five days that calling it Day 5 would lead you to believe. This happened on Friday, the fourth day of my lock-up.

The next thing that broke me was when my first test came back positive. For six days I had paced back and fourth, pulled on my hair, and counted down the minutes until I could learn that I would soon be free.

There is nothing quite so detrimental to the psyche as hope. For six days it was the only thing I had, and then in one 30 second interaction with the ever cheerful doctor, I was crushed. Don’t forget: every one positive test meant two more days of prison. From then on, I had nothing to look forward to.

• • •

As miserable as my Expedition 397T experience was turning out to be, there were some small lights on the dark horizon of isolation. I am grateful to Will, Daniel, Luan, and Nick who took the time to send me pictures that I could post to our social media pages, so that I could still perform some of the duties of my job as Onboard Outreach Officer. I am indebted to Glenn, who not only sent me daily pictures and videos of the goings-on on the drill floor, but also used Messenger to check in on me hourly and even left some chocolate (the most valuable currency on the JR) outside my door. I owe my sanity to Peter, our Expedition Project Manager, who not only scheduled Zoom meetings twice a day so that those of us in quarantine could interact with the free scientists, but also convinced the captain and the doctor to let us outside for 30 minutes a day so that our eyes could see natural light and we could feel the sun on our skin. I am soul-bonded to my fellow “isolationists,” who kept me smiling through frequent [often snarky] email updates about their own quarantines.

• • •

My second negative test finally came on the morning of my eleventh day in quarantine. I stumbled out of my room like a newly born cave-dwelling creature, blind and confused. People crowded around me, ecstatic that I was finally out, and curious to hear about my experience. I realized I had forgotten how to have normal social interactions.

Ten full days (plus several hours) of isolation with no windows was horrible.

But what would have been worse is if I passed my infection onto someone else, and it spread around the ship. I am in good health, and weathered the virus with minimal consequences. Not everyone would have been so lucky. If I didn’t isolate when I did, more people could have gotten sick, putting the success of the expedition at risk. More people could have gotten seriously sick, putting their lives at risk. I’m glad that didn’t happen.

And the best news? I won’t have to worry about getting COVID for a long time.

*in hindsight, the irony of this is overwhelming