Freeeeeee Fallin’ [funnel]

Imagine trying to get the end of a string into a thimble. But wait. You’re attempting this from on top of a six story building. Oh, and it’s windy. (If you’re wondering why the heck you would want to do that, don’t worry. I’ll get there.)

This incredible feat was accomplished by the JOIDES Resolution on January 28th as part of the drilling process at our final site, CT-05A.

DIGGING DEEPER

As per the scientific objectives of Expedition 391, our goal at this location is to drill as deep a hole as possible. Site CT-05A is located on the central track of the “trident” of Walvis Ridge, and may hold invaluable clues to the origin of this strange underwater mountain chain deep in the oceanic crust. You can read more about the motivation behind this investigation here.

Drilling an extra-deep hole is made complicated by the fact that our drill bits eventually wear out when we drill into hard igneous rock. If we want to keep drilling, we need to pull the drill pipe up, change the bit, and then send a fresh new bit back down to keep digging.

Simply pulling out of the hole and going back in is not an option. Compared to the size of the ocean, even compared to the size of our ship, the hole is TINY. We need a way to guarantee that we can find it again, and that when we get back down we will be able to get the drill back into the hole. This brings us to…

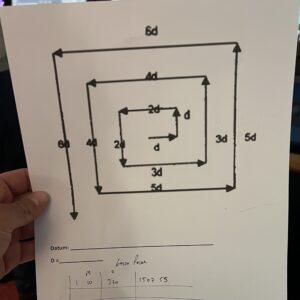

THE FREE-FALL FUNNEL

Engineered in the days of the Glomar Challenger, the free-fall funnel is a high-visibility device designed to make it easier to reenter a drill hole. Around 18:45 on January 27th we released the funnel, allowing it to fall freely down the drill string to the ocean floor. It was followed by an assembly that included several lights and cameras so that we could inspect the funnel after it landed.

This brings us back to the analogy of a string and a thimble in a windstorm. The reentry process is much more challenging than it sounds, taking concentrated collaboration over a nail-biting several hours. Read on to learn how it’s done.

THE TEAM

Finding and reentering the hole takes a team of three intensely focused individuals who need to communicate clearly and work together.

(1) The captain. Captain Jake constantly monitors the video feed and adjusts the dynamic positioning system accordingly. He moves the ship one meter at a time to search for the funnel, then to steer the ship into position.

(2) The cameraman. Bubba is on call with the captain to adjust the camera as needed so that Captain Jake can see where he needs to go.

(3) The driller. Rodney is alert on standby, waiting to drop the drill string at the exact right moment. As soon as Bubba says “GO!” he releases the brake, so that the compensator can send the drill down into the hole.

THE PROCESS

As I’ve alluded to several times, this is not an easy task. In our case, it was complicated from the start. We dropped the free-fall funnel into a pile of soft, soupy sediments, where it immediately sank into the seafloor. (Caption: imagine dropping a weight into a tub of melting ice cream) Luckily, the impact of the funnel left a circular depression in the sediment, and the captain was able to record the exact GPS coordinates of the ship when we deployed the funnel.

With confirmation that the outline would be discoverable by camera in the future, we pulled out of the hole. Tripping the pipe back up to change the bit would take about seven hours, and then we would send the pipe back down with the camera attached to look for the hole and reenter.

Sending the pipe back down to the ocean floor is not a simple matter of the ship being in the same place it was when we dropped the funnel. Even though the drill pipes are made of steel, a string of them over 3800 meters long is surprisingly flexible. Currents can push the string in any direction, and even the slightest movement of the ship sends a wiggle down the pipe, just like a wave through a piece of rope.

When our camera finally made it back down to the ocean floor, the funnel was nowhere to be seen. This was unfortunate, but not the end of the world. The captain has the video feed and sonar in his office, so the lack of visible funnel just meant it was time to start the hunt.

There is a plan for what to do if the funnel is not visible: move the ship in an outward spiral, one meter at a time. This search pattern, used by members of the coast guard and navy to search for people lost at sea, is a surefire way to eventually spot what we were looking for.

After about forty minutes of fine maneuvering, we finally spotted the edge of the funnel depression on our camera field. You’d think that this meant the hard part was over. But we were just getting started.

The first obstacle to overcome was an issue of navigation. We could see where the funnel was relative to the drill pipe, but we had no way of knowing which direction that was in relation to the ship’s heading. Though the camera records how its heading changes as it falls down the drill pipe, the measurement is approximate and unreliable. This means that Captain Jake had to attempt to move the ship in one direction, see how the position of the funnel changed on the camera screen, then readjust accordingly. As if this wasn’t difficult enough, don’t forget that the movement of the ship does not fully correspond to movement of the camera, again because of how flexible the drill pipe is.

Another thing to consider was the placement of the drill pipe. The funnel was resting in very unstable sediment, meaning that if the drill were to hit the side of it, rather than the exact center, the funnel could tip over and block the hole entirely. The only way to guarantee reentry was to ensure that the drill would go directly into the middle of the funnel cone.

SUCCESS!

It took an hour and twenty-one minutes from the initial sighting of the funnel to the drill successfully reentering the hole. I found myself holding my breath every time the captain adjusted the ship’s position, waiting to see if we would move closer or not. For several minutes, we circled around the funnel, every move bringing us slightly closer but still not perfectly in place.

Eventually the moment was right: Jake guided the drill over the center of the funnel, Bubba gave the word, and Rodney successfully dropped the drill exactly where it needed to go. We were in. Time to get back to coring.

rich story telling about an incredible feat! well done!