Oh Fudge!

I like visiting the nook on the far side of the core lab where paleomagnetist Courtney Sprain hangs out. She’s a gracious host, happy to entertain curious interlopers, “What would happen,” I ask, “if I was out at sea with only a compass, and our planet’s poles were reversing, as they periodically do?

(Answer: Since it can take 10,000 years or so for polarity to flip, I’d be lost for a very long time.)

Explaining that the orientation of the Earth’s magnetic field is locked into most rocks when they are formed, Courtney shows me a 5-foot-long paper print-out on the wall near her work station: the geologic time scale. Its black-and-white pattern, which looks like a very long bar code, is the geomagnetic polarity time scale.

I want to know why the uppermost part of the chart—which is recent history—has relatively short black and white intervals compared to the bottom part of the chart, which is dominated by one very long black interval.

I want to know why the uppermost part of the chart—which is recent history—has relatively short black and white intervals compared to the bottom part of the chart, which is dominated by one very long black interval.

These intervals, known as chrons, indicate when polarity stays in the same direction for a period of time. The long black interval is a superchron, Courtney explains: When polarity stays in one direction without changing for tens of millions of years. Not just any old superchron, the bar that spans many inches—longer than any other—is the Cretaceous normal super chron. Normal indicating that the polarity was in the black, like it is today, with compasses pointing North. It stayed that way without reversing for 40 million years.

The Cretaceous is, of course, of great interest to the scientists of Expedition 392. Among their major aims is investigating the long-term climate transition from the Cretaceous greenhouse—when palm trees grew on an ice-free Antarctica—to the late Paleogene icehouse, which is the period we are living in now.

The willynilly widths of black and white on the chart reveal that polarity flips in a beguilingly random way. No one knows when this will happen next. As for why polarity sporadically changes, Courtney tells me it’s related to chaotic motion in the Earth’s liquid outer core.

I simply don’t get magnetism, I admit. Courtney shrugs, “Most people don’t.”

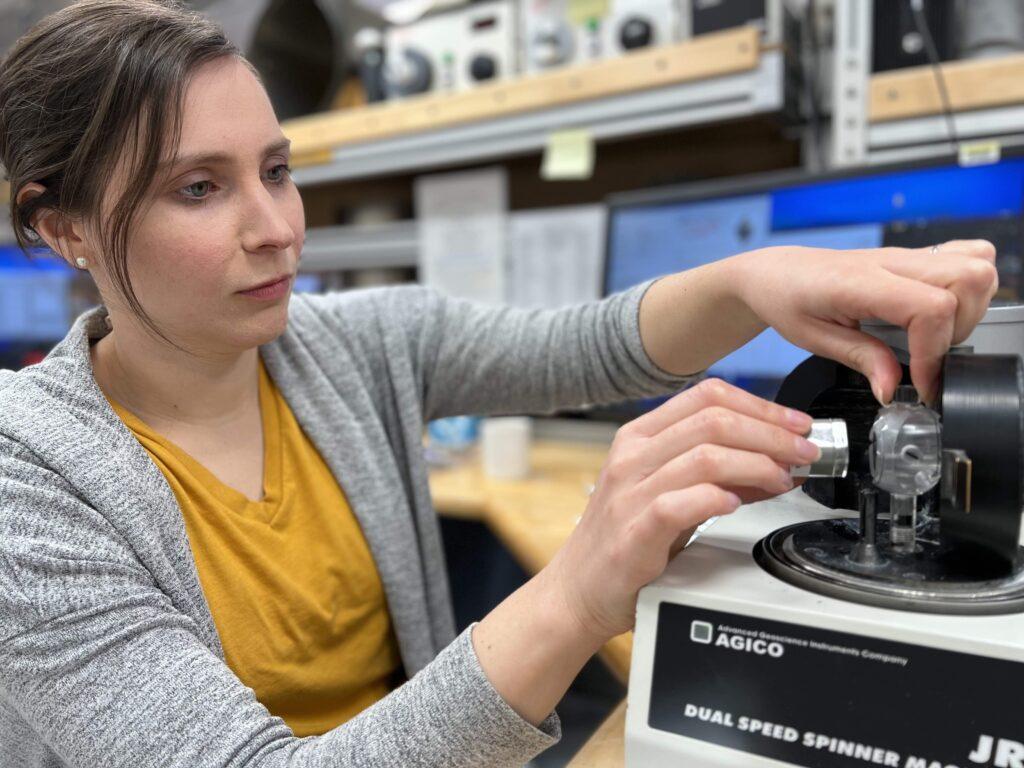

If it weren’t for Courtney, the paleomag lab would be an intimidating place, with its spinner magnetometer and super conducting rock magnetometer, complete with detectors known as SQuIDs: Super-conducting Quantum Interference Devices. Yikes.

A peculiar pirate-monkey plastic toy stands guard over these magnificent machines. “He keeps all our equipment working,” Courtney says. He also adds to the otherworldly whimsy of this seafaring science lab, one that’s reminiscent of the fantastic underwater cavern about which Ariel, the Little Mermaid, sings: I’ve got gadgets and gizmos a-plenty, I’ve got whozits and whatzits galore. You want thingamabobs? I’ve got twenty!

Courtney’s beeping gadgets and spinning whatzits measure the magnetization of sediment and rock. Which, she explains, “can tell us about magnetic directions and the polarity of the magnetic field when the sediments were deposited.”

Her work here is about understanding how the magnetic field has changed through time in the cores that we’re retrieving.

She shows me how she feeds the spinner magnetometer cubes cut from the working halves of cores recovered from hundreds of meters below the sea floor. Despite no lack of state-of-the-art equipment, her methods to cube the cores are decidedly low-tech. She saws the rocks, and simply pushes clear plastic boxes into sediment, essentially filling them up.

The resulting nuggets are dangerously similar in appearance to pieces of candy. And not just any candy.

Early on in the expedition, co-chief scientist Gabi Uenzelmann-Neben remarked about how closely the cubes resemble fudge—which just so happens to be one of Camp Boss Ally’s most special homemade specialties.

One day, Gabi filled a cube with bona fide fudge and snuck it into the paleomag lab, leaving it with a note that said: “mystery cube Courtney?”

Right away, Courtney suspected sedimentary shenanigans.

“That cube,” she said, “wasn’t the right color.”

No gadget or gizmo was required. And, importantly, no fudge was wasted.

I loved reading your article! It sounds like you all are having fun on the ship! Dr. Sprain was my professor last semester, she is wonderful! She is always happy to help and listen to any questions you may have