Previous scientific expeditions in the Ross Sea (from DSP to Expedition 374)

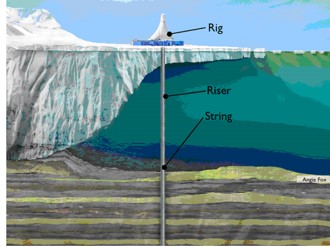

In 2006-2007, the multinational ANtarctic geological DRILLing (ANDRILL) brought together a team of over 200 scientists, drillers, and technicians. They spent a combined six months on the Ross Ice Shelf over two seasons. They drilled 2 holes through several hundred feet of ice and ocean water to reach the marine sediments. These sediments are the memory of past climate. They contain the ice sheet history of the Ross Ice Shelf.

Scientists wanted to learn more about how this ice sheet has behaved during warmer conditions than today, especially during MMCO (Mid Miocene Climate Optimum) and during the Pliocene warm period. They discovered that west Antarctica ice sheet was dynamic during these two periods and there was an interval of time, particularly warm, when the ice sheet was very much reduced, compared to today.

Expedition 374 will not be the first expedition to drill in the Ross Sea. The first drilling expedition in the Ross Sea was DSDP (Deep Sea Drilling Program) leg 28, with the Glomar Challenger in 1973. At this occasion, scientists discovered for the first time that Antarctica had a much longer history of glaciation than the northern hemisphere.

Since 1973, the technologies of drilling have improved and many seismic data have been gathered. Today, scientists know much better where to drill in order to recover the missing information about the ice sheet history from the Ross Sea.

Andrill sites record the ice sheet history in an area that is close to the mountains and to the Ross Ice Shelf. The cores that we will collect during Expedition 374 will be further off shore and they will provide information from near the edge of the ice sheet, during the maximum advance over the continental shelf, and where these ice sheets were more directly connected to the Southern Ocean. Having all these data to compare will help numerical models to improve in their accuracy. Their results can be put in perspective with the real records and if they are enough accurate to predict the past, they will be reliable to predict how the ice sheet will evolve in the future, in warmer conditions than today.

By having a better knowledge of the past, we could have a better understand of what the future might be.