Remarkable Shades of Grey

It’s just after midnight, and I have raced upstairs to check in with the science team. What has happened while the Night team has been sleeping? Has the Day team found something new? As I enter the core lab, there’s the same slow, rhythmic whirring of the logger and the wheezy heartbeat of the magnetometer’s cryocooler. The same night crew buzzing back and forth with split cores and technicians donning safety gear, awaiting the next core’s arrival… yet something is very different.

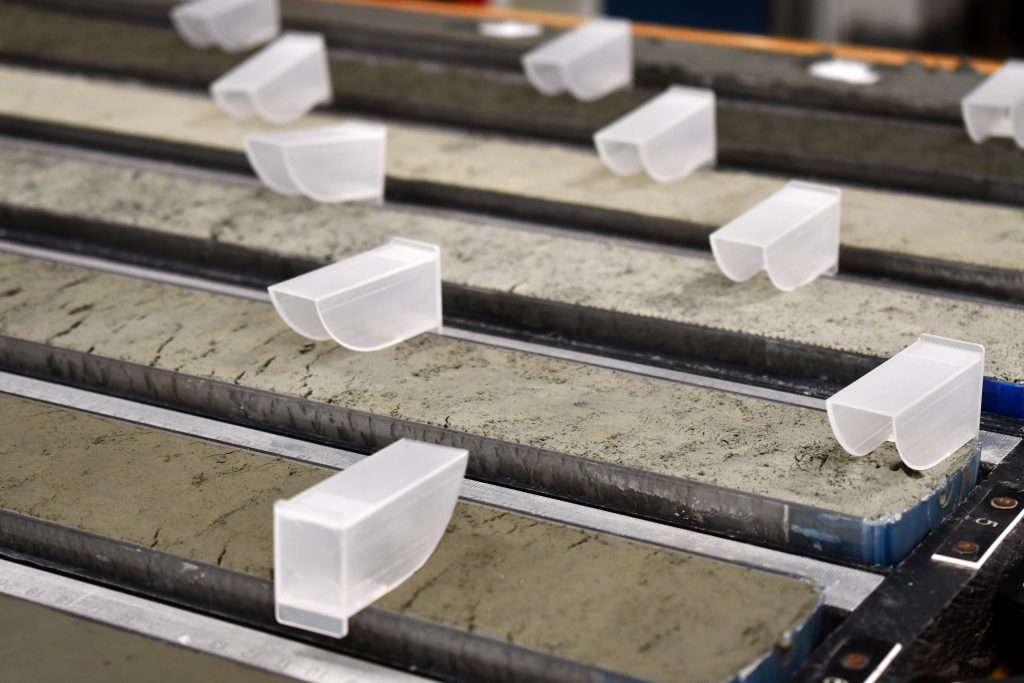

It’s immediately obvious. On the sampling table are the usual seven core sections, but instead of the more or less homogenous greenish-grey mud we’ve seen for days, several shades of lighter grey lie before me, and one core that’s markedly light in color. I can even see, in the core beside the palest one, a clear transition from mid-grey to this light material.

“I’m really excited,” says Anna Glüder. “And it’s beautiful. It’s not often I get to work with cores that are not only interesting but beautiful.”

Co-Chief Scientist Maureen Raymo is the expert on MIS 11. “It’s one of the extreme warm interglacials in the late Pleistocene.” It’s a period in which the climate was probably 2 degrees Celsius warmer. “Sea levels are estimated to have been about 9 to 12 meters higher.”

Looking at the sediment can tell us a lot about the environment at the time it was deposited.

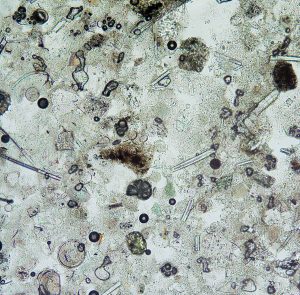

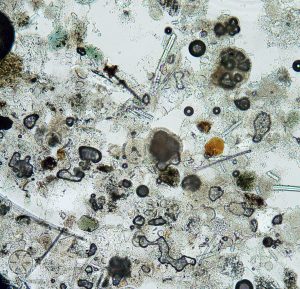

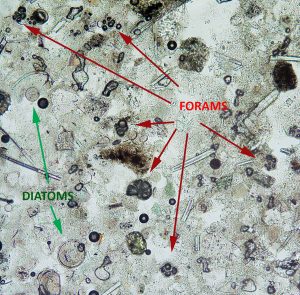

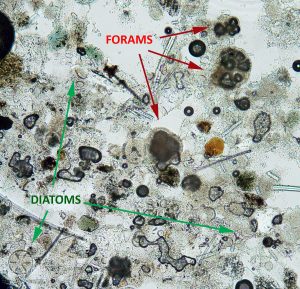

Diatoms (a kind of tiny plant) and radiolarians (a kind of tiny animal) have skeletons made of silica. Forams and nannofossils are made of carbonate. It’s the balance of silica vs. carbonate microfossils in the sediment record that tells us who was winning the competition for survival. Diatoms and radiolarians prefer cooler conditions, while forams and algae thrive in warmer conditions. So, when we start seeing sediment rich in carbonate, like the pale sediment we’ve found, we know the climate was warmer when that material was deposited on the seafloor.

We looked at some of this carbonate-rich sediment under the microscope, and this is what we saw. There are several forams in these images. They look a bit like ammonites (which look a bit like snail shells). There are also some diatoms; they look like round discs with spots (pores), and one looks a lot like a sand dollar. Can you find them?

“If we could get this kind of signature in the Scotia Sea,” says Mike, “so you have some iceberg-rafted debris and you see where those come from during MIS 11, that would give us a good indication as to what actually happened in Antarctica. Our records can hopefully tell us something about that if we have that time period preserved.”

We won’t know until we start drilling at our southern sites, and that time is coming. Sometime in the next couple of days, we’ll leave our northern drilling sites, bound for the Scotia Sea. None of us can wait to see what we’ll find!

Keep scrolling down to the end of this post to find out if you found the forams and diatoms!

↓

↓

↓

Keep going!

↓

↓

↓

Don’t stop now!

↓

↓

↓

Did you find them? (And if you’re wondering what the very long, skinny fossils are, they are sponge spicules, part of the structure of sponges.)

I wonder how deep these cores were from?