The Heroic Age of Antarctic Exploration

Our expedition to the Ross Sea echoes the journeys of Antarctic explorers more than a century before us. This very area is where the famed Ernest Shackleton, Robert Scott, Roald Amundsen, and James Ross strode out onto the ice to begin their epic adventures, some of which ended in disaster and others in triumph.

What is known today as the Ross Ice Shelf used to be called The Barrier, because it was a barrier from sailing farther south. Explorers brought their wooden ships with specially strengthened hulls to search in vain for a straight shot to the South Pole through the sea. But every time, the enormous ice blocked their path.

So explorers would instead purposely wedge their ships into the ice and overwinter there for 8 months, building stations the remnants of which still exist today. There they waited, until the weather warmed enough to provide a small window of opportunity to make a dash across the ice to the South Pole. While they waited, men in dog teams went ahead to lay out depots stocked with food and other necessities that would be critical to the later South Pole dash. Getting to the South Pole from the Ross Ice Shelf involves navigating deadly crevasses in the ice, scaling the Transantarctic Mountains, and skiing across a barren polar plateau of soul-numbing whiteness.

You work all day hauling your gear, sweating underneath your many layers and yet trying to wick off the sweat so it doesn’t make you too cold. The reflected sun off the ice is nearly blinding and your eyes sting and your skin burns. Your lips become so chapped from the dryness that they bleed. The wind whips your cheeks and makes it hard to hear. There is nothing green to look at, no civilization nearby, only an endless taunting horizon of ice, and your companions struggling in formation behind you. When a day of trekking is done, you build your own campsite and eat the same food you’ve had for months. Antarctica is extreme – I struggle to imagine much harsher traveling conditions, both physically and mentally. If you ever feel like complaining, read about the struggles of Antarctic explorers. In 1911, the entire journey from Ross Ice Shelf to South Pole took about 3 months.

The Race to the South Pole

One of the most epic rivalries in history is that between Robert Falcon Scott and Roald Amundsen. In 1911, they raced to reach the South Pole.

Scott and Amundsen couldn’t be more different. Scott was personable, beloved in his home country of the UK, a naval man with a somewhat aristocratic background, given to grandiose statements. The Norwegian Amundsen was above all else pragmatic, practical to a fault, introverted, understated, sometimes difficult to deal with. Both had made attempts at reaching the Pole before; both had failed.

Amundsen had studied the survival methods of the indigenous people in the Arctic and based many of his preparations around the lessons he learned there. Amundsen and Scott both used dogs (which, though deeply beloved by the men who depended on them, would eventually be shot and eaten when times got rough), but Scott also brought ponies and a kind of early snowmobile, which took up unnecessary space and proved useless in the end.

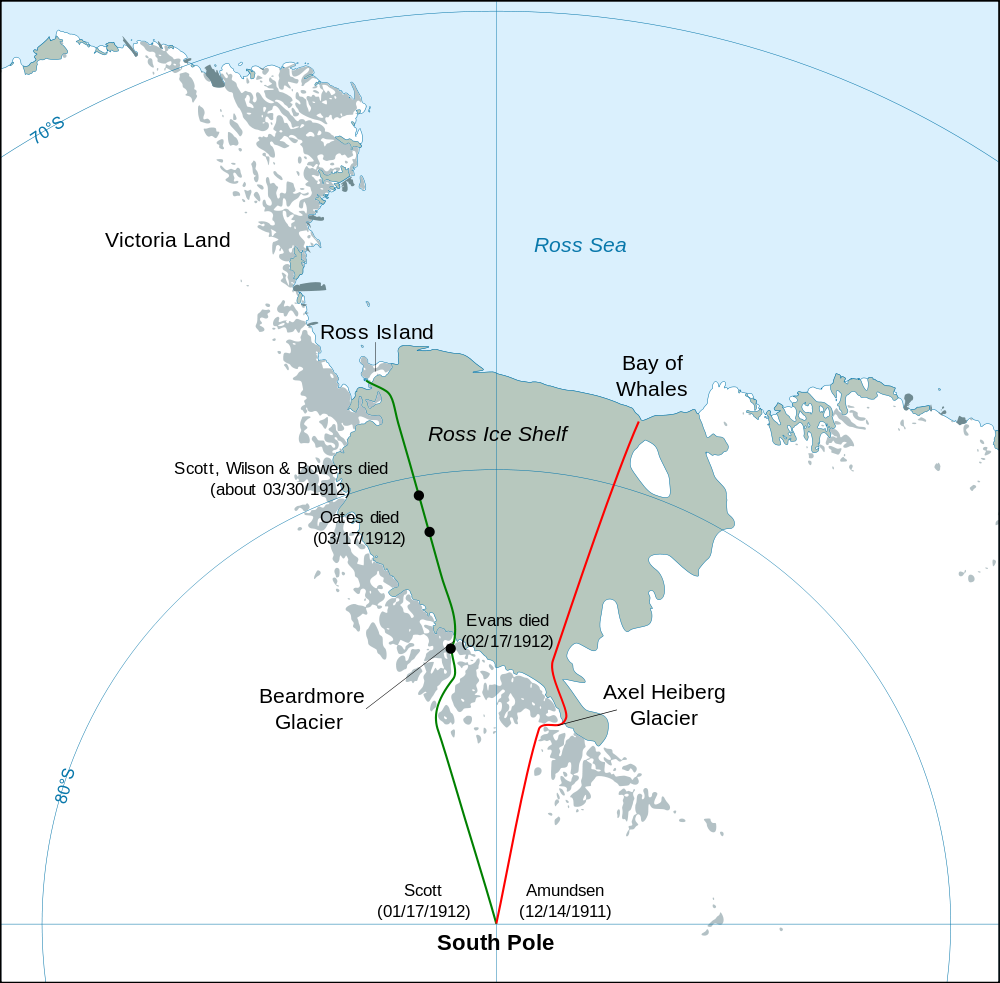

Scott’s plan was to start with a larger party, with men gradually turning back and leaving supplies along the way like breadcrumbs for the return journey. The whole party was 65 men, but only a small group of five would complete the final stretch. Amundsen started and ended with five, and laid out supplies earlier in the year; they didn’t need as much with less people. His entire team included 19 men. Amundsen started at the Bay of Whales and a more unstable place on the ice – he risked falling into the water, but was located closer to the Pole. Scott began at Ross Island (where the current American research base, McMurdo, is located), which was much more stable but also farther away from the Pole.

Scott took a better-known route, whereas Amundsen found a new route through the Transantarctic Mountains onto the Polar Plateau. Both Scott and Amundsen had essentially the same diet – pemmican (an atrocious mixture of fat and protein meant to be amply nutritious), chocolate, powdered milk and biscuits. Scott opted for man-hauling his gear part of the journey – a noble-looking method but exhausting – whereas Amundsen spent more of the journey on sledges pulled by dogs, and then later on skis. Scott brought along a man to train his men on how to ski, but (perhaps because he was Norwegian) this man wasn’t included in the South Pole party and only some of Scott’s party learned to ski. All of Amundsen’s team were well experienced skiers. Amundsen wore furs, something he’d learned from the peoples of the Arctic. Scott’s team wore woolen clothing, which didn’t let the sweat evaporate as easily, and so made the men colder.

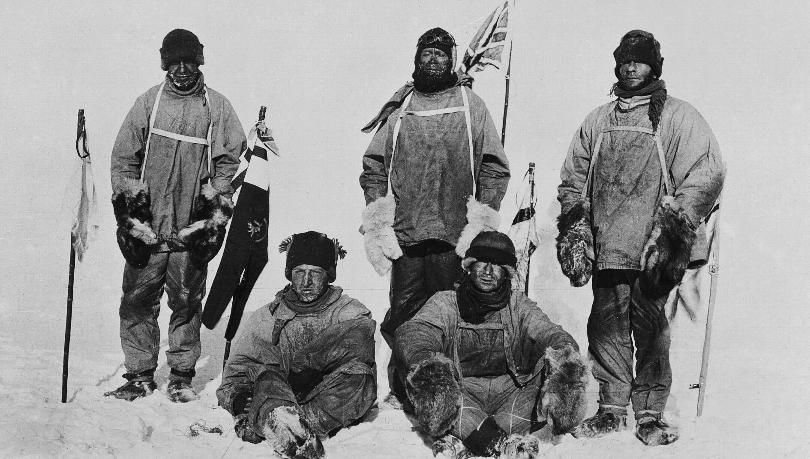

Amundsen won the race. He beat Scott by about one month, arriving at the South Pole with four other men in December. Scott and his four other men reached the slept in the same hut in January 1912, bitterly disappointed and now faced with the enormous task of getting home.

Time was running out because Antarctic summer was almost over. Unexpected cold, blizzards, and ice that made man-hauling difficult slowed Scott’s team down. It was taking longer, so they reduced their daily food rations, and began to starve. One man died a month after reaching the Pole. Four weeks later another man walked off into a blizzard, essentially sacrificing himself so his comrades could push on, with the last words “I am just going outside and may be some time”. The remaining three needed to make it to the last depot, but blizzards kept them shut up in their tents. There they died sometime in March 1912, 10 weeks after reaching the Pole, just 18km (11 miles) from the depot. Scott’s famous last diary entry on March 29 was: “for God’s sake look after our people”.

Meanwhile, Amundsen and his men all made it back to their base on the other side of the Ross Ice Shelf alive. He later led an air expedition to the North Pole in 1926, making him the first person to reach both poles. He mysteriously disappeared in 1928 while taking part in a rescue mission; his plane was never found.

Scott and Amundsen and their race to the South Pole is perhaps the most famous story of Antarctic exploration. The Heroic Age of Antarctic Exploration of the late 19th century was preceded by the more commonly known global Age of Exploration of the late 18th century. During this time period, James Cook was the first human to realize Terra Australia didn’t occupy most of the Southern Hemisphere and that in fact there was probably a large continent of ice down south instead. Then in the mid-1800s, explorers for which much of Antarctica is now named – Bellingshausen, Wilkes, and James Clark Ross – return to learn more. The region we are currently in is named after a man who led two ships the HMS Erebus and HMS Terror in an expedition in 1841. The Belgians kicked off the Heroic Age of Antarctic Exploration in 1897-99 on the Belgica (Roald Amundsen was First Mate) and was the first expedition to overwinter within the Antarctic Circle.

Back to 2018 – we are on a research drilling ship, hovering over a carefully selected patch of ocean floor that we have stuck a drill bit into, and which yields long cylinders of mud we carefully examine for science. We are in the Ross Sea, near the Ross Ice Shelf. We cannot see the ice from here, and in fact the ocean around us is relatively calm, with small waves and little current. Intrepid adventures before us sailed through these same waters on their way to face the continent of ice. We are drilling beneath the sea floor to learn more about what that ice did long before they were born, before we were born, before humans even existed. Though it’s a different kind now, we are still in an age of exploration.