Dada TV

When it comes to geologic time, I am as dense as the 70-plus-million-year-old basalt we just recovered on the Agulhas Plateau.

Despite living for two months with scientists who, fueled by espresso, expertly go about their business of measuring Earth’s 4.6-billion-year history by focusing on the planet’s rock records, my grasp of eras, periods, epochs and ages remains muddled and melted. Like a Salvador Dali clock.

I do know that in geologic time, two months isn’t even a blip; it’s probably not even a zeptosecond much less a moment. So I really wasn’t fibbing back in January when I kissed my pup Tess goodbye and promised that I’d be home soon.

With just a few days left until the JR docks in Cape Town, soon feels eons closer than when the “pet wall” started taking shape in early February. I’m not sure who was the first to tape their pet’s likeness in the main stairwell just outside the core lab, but by the time I added Tess’ photo, there already was a montage of dogs, cats, bunnies, fish . . . even a bearded dragon.

With just a few days left until the JR docks in Cape Town, soon feels eons closer than when the “pet wall” started taking shape in early February. I’m not sure who was the first to tape their pet’s likeness in the main stairwell just outside the core lab, but by the time I added Tess’ photo, there already was a montage of dogs, cats, bunnies, fish . . . even a bearded dragon.

That wall is a double-edged sword of guilt and longing. On any given day, its furry cuteness slays me.

This business of leaving behind best friends and families is hard. Work that requires a person to untether from the familiar—to head to remote places for long stretches—takes a toll. Even on those who spend as much time away as at home. Like Dave Doran, for instance.

Dave’s been a driller for 23 years—the last four on the JR. “You miss out on a lot of things,” he says over the squeal of brakes and hiss of air pressure that fill the shack (which he calls the dog house) where he works 12 hour shifts adjusting knobs and pushing levers. He spends 2 months on the ship, then has 2 months off. Home is in a small village north of Glasgow, Scotland, with his wife and two teenaged sons.

The science team has been surprised about the dependable connectivity we have on the JR. Sedimentologist Don Penman regularly visits with his daughter Juniper via Zoom, which the 2-year-old calls “Dada TV.” At lunch recently, he and co-chief scientist Steve Bohaty, whose daughter is 4, debated about when it is that children begin to understand the concept of time.

Clearly, 8-year-olds know exactly what’s going on, co-chief Gabi Uenzelmann-Neben says, referring to her son Leif, now 27. Back in 2003, Gabi told him she was going away for 7 weeks. His reaction: “That’s 49 days!”

Transitions were tough, she says. The first time that work at sea took her away from him, he turned 1. Missing the birthday itself didn’t affect her nearly so much as a baby crying during her flight from Germany to the ship: “That hit me really hard,” she recalls.

During this current expedition, she often speaks with Leif, most recently to tamp down his nervousness about defending his bachelor’s thesis. She says, “I don’t think it gets less critical to be there for them as they get older.”

The youngest baby not-on-board the JR belongs to physical properties specialist Matt Jones. If you ask him how Theo is, he’ll beam and pull out his phone to share a video of his 9-month-old taking his first steps.

The youngest baby not-on-board the JR belongs to physical properties specialist Matt Jones. If you ask him how Theo is, he’ll beam and pull out his phone to share a video of his 9-month-old taking his first steps.

Matt’s pride is visible. His pain, palpable. He missed being in person for the big event.

It was during a video chat with his wife that Matt saw Theo wiggle free from his mom’s lap and make his way across the living room, progressing—as the young dad watched breathlessly—from wobbling to walking.

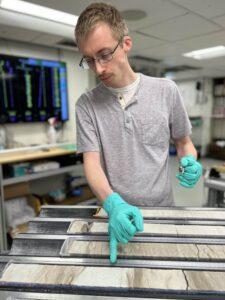

“Two months is a long time to be away,” Matt says. “But it’s by design. We had to travel far to get to this unique site on the Agulhas Plateau. And it takes time to figure out what we’re working with and what the best strategies are. Coring, not always a fast process, throws lots of curve balls. It requires a dedicated chunk of time to see the mission through.”

Among this mission’s notable successes was the recovery of a core that shows evidence of a mass-extinction event of 66 million years ago, when an asteroid hit the planet, ending the Cretaceous period.

While marveling at the Cretaceous-Paleogene (K-Pg) boundary, Matt said, “These are the most consequential centimeters of geologic history for humans and mammals, because it marks the end of the Mesozoic Era, when dinosaurs went extinct, leaving massive openings in ecosystems on land and sea for new species to step into.”

While marveling at the Cretaceous-Paleogene (K-Pg) boundary, Matt said, “These are the most consequential centimeters of geologic history for humans and mammals, because it marks the end of the Mesozoic Era, when dinosaurs went extinct, leaving massive openings in ecosystems on land and sea for new species to step into.”

Theo’s first steps, he says, are analogous to the K-Pg boundary in that they mark the end of an era and the start of a new one. First steps are monumental, setting into motion a being’s escape velocity. Then comes riding a bike, then driving a car . . .

And soon (there’s that word again) they’re gone.

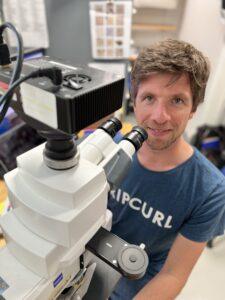

Micropaleontologist Peter Bijl can doubly relate. A dozen years ago, when he was on the JR, his twins took their first steps. During video calls to the Netherlands, he watched both become toddlers who, free at last, were eager to taste house plants, finger electrical sockets and explore drawers full of sharp implements.

Micropaleontologist Peter Bijl can doubly relate. A dozen years ago, when he was on the JR, his twins took their first steps. During video calls to the Netherlands, he watched both become toddlers who, free at last, were eager to taste house plants, finger electrical sockets and explore drawers full of sharp implements.

The parent who’s far away has no lack of vivid imagination. And is particularly prone to self-flagellation—to a degree that would impress even a dinoflagellate, which is the creature that most captivates Peter.

Dinoflagellates (DFs) are mobile thanks to two flagella. Like Peter’s now teenaged sons—and Matt’s newly minted toddler—DFs go where they will.

When a DF is less than comfy cozy—maybe it’s dark, or it’s winter—it builds an organic capsule, a sleeping bag of sorts. Its metabolism slows. It loses mobility. Now a cyst, it becomes slave to ocean currents, floating free for a bit as it sinks to the sea floor.

The dinoflagellate story doesn’t end in muddy oblivion, however. When conditions improve, a DF will crawl out of of its sac and propel toward light. To assess the ages of sediment samples, Peter analyzes lots of cysts with holes in them through which DFs have escaped.

In addition to appreciating DFs for allowing him to determine the geological age of sediment, Peter also respects these little charmers. They bio-luminesce! And produce deadly toxins.

While some photosynthesize, others are voracious predators that hunt by shooting harpoon-like appendages. They can take down prey that is many, many times their size. Kind of like if I jumped on a buffalo, Peter says, and straightaway started ingesting and digesting.

“They are beautiful,” he observes, “in the same way that the wolf, lion and killer whale are beautiful—best admired from afar.”

Admiring beautiful creatures from afar brings this story full circle, in a melting clock kind of way. After months at sea, we are full-throttle antsy to be together again with those we’ve left behind: to hug, chase down and cuddle with all who are furry, fleet-footed or fans of Dada TV.

P.S.

Twenty-four years ago, while working for more than a month in Madagascar, I missed my first-born’s first day of first grade. I remember the jump-out-of-my-skin desperation I felt when powering up a fickle satellite phone in the dripping rain forest surrounding my tent, attempting to call just as she arrived home. Tears streamed down my face when she said, “Hi Mommy!” and while she prattled on about her teacher, the other kids, her first bus ride. . .

As I write this, I’m all knotted up about missing that same child’s 30th birthday. Lucky her to be on a beach, celebrating with her fiancé. And lucky me to have good work involving travel and spanning decades.

###

With gratitude to the International Ocean Discovery Program for inviting me on board the JOIDES Resolution as Expedition 392’s Outreach Officer. And a special thanks to all who graciously shared their science, their stories.

Brilliant. (And Caroline seems no worse for wear!)