Exquisite Worlds

“May I look?” (It’s a question scientists are used to me asking.)

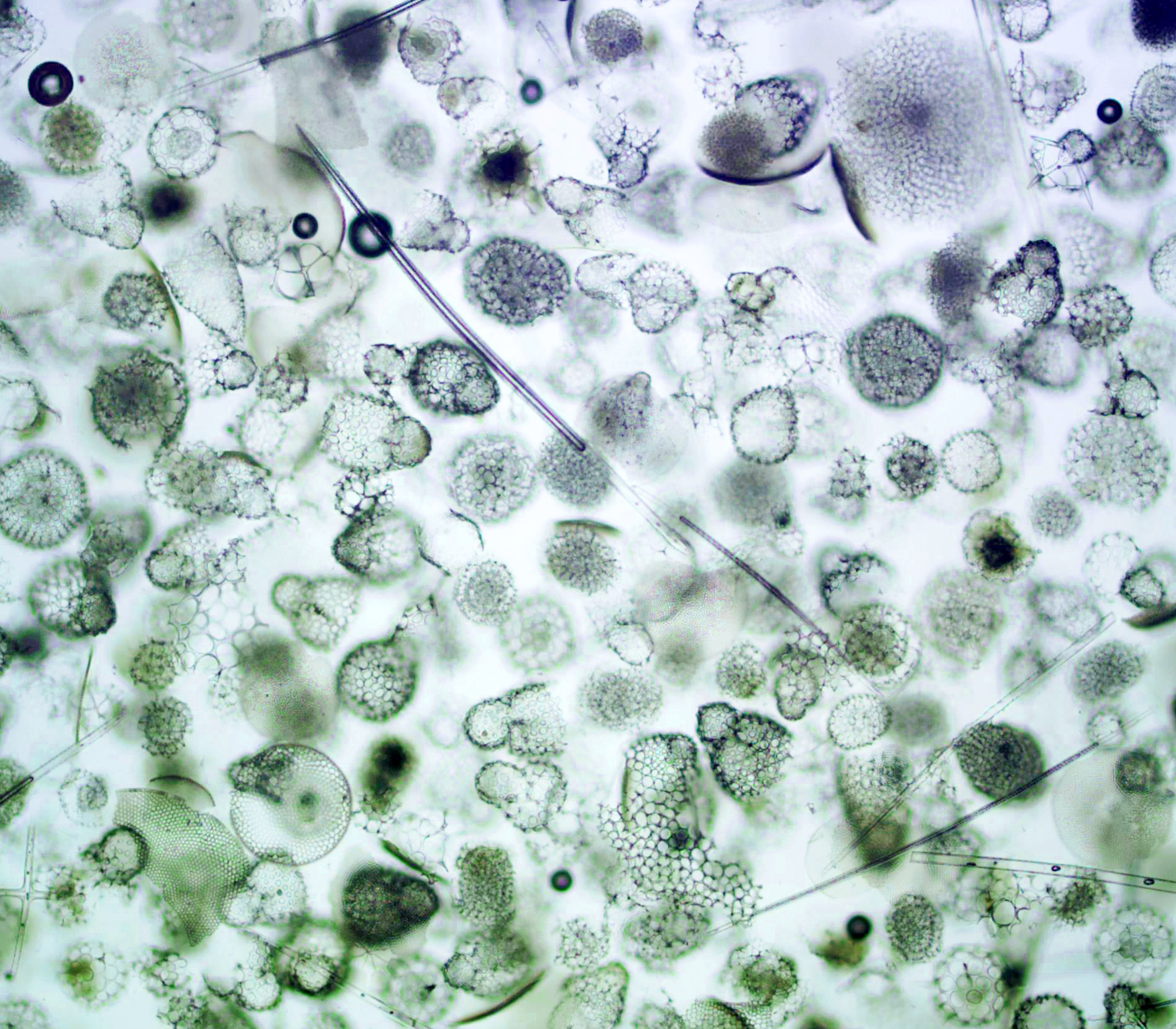

With a thrill of anticipation, I slide into the seat before the microscope. As I adjust the focus, intricate shapes become clear: concentric circles and delicate webs, spines and whorls, turreted castles and horned aliens, all tiny skeletons made of silica or carbonate. Miniscule creatures vital to Earth, yet these ones lived millions of years ago.

I love working in the biostratigraphy lab, where the micropaleontologists are, so I can sneak frequent peeks at these discoveries. Micropaleontologists study microfossils—fossils too small to be seen with the naked eye. On Expedition 382, they use these to establish an age range for the sediment.

Because we know the times at which various species lived and became extinct, when our team finds a certain species that lived until, for example, 2 million years ago, they know the sediment is older than that time*. When we find iceberg-rafted debris in the same section of sediment, we know it was deposited by an iceberg that calved at the same time. This will help us understand when parts of the Antarctic Ice Sheet were melting.

These organisms are fascinating in terms of the role they play on Earth and in their extraordinary complexity and beauty.

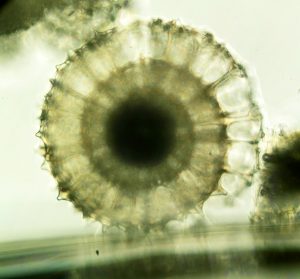

Radiolarians

[Credit, including featured image: Iván Hernandez-Almeida]

Radiolarians are microscopic animals living in the ocean. They are unicellular and build their skeletons out of silica. They feed on a variety of food sources and are an important part of the ocean’s microbial loop. They capture their prey (such as bacteria, diatoms, and other small algae) with pseudopods and export organic matter from the surface to the deep ocean. Radiolarian shells show an amazing range of shapes and patterns, sometimes very complex.

~ Dr.Iván Hernandez-Almeida, radiolarian specialist

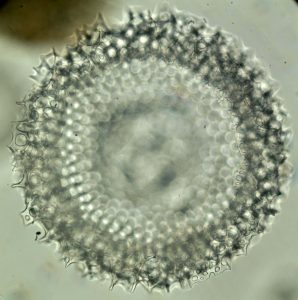

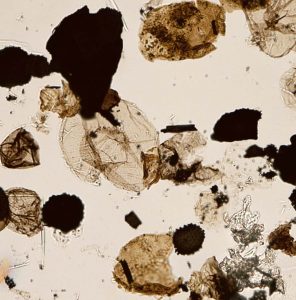

Diatoms

[Credit: Yuji Kato]

Diatoms are small unicellular plants with cell walls made of silica. Their distinctive feature is the beautiful pattern of the siliceous walls that differ from species to species. We can say diatoms are one of the most widespread groups of plants on Earth. So, you can find diatoms in every aquatic habitat where water and sunlight are available (e.g., ocean, lake, river… and even on the moist surface of moss and rocks!!). They play an essential role in the ecological system, and fossil diatoms give us an important clue about environmental history in the geological past.

~ Dr. Yuji Kato, diatom specialist

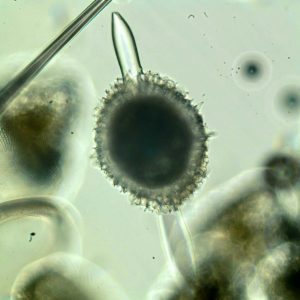

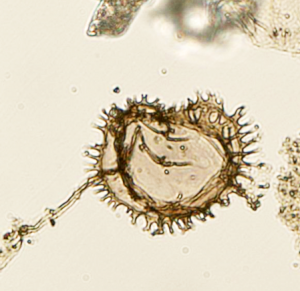

Dinoflagellates

[Credit: Frida Snilstveit Hoem]

Dinoflagellates are single-celled organisms living in the surface ocean with resemblances to both animals (motility, ingestion of food) and plants (photosynthesis). The different species of dinoflagellates have specific preferences in living habitat controlled by temperature, salinity, and nutrient availability, and species appear and go extinct through time. Some produce a resting stage or cyst with a resistant organic wall that can be preserved in the fossil record. By studying the different assemblages of dinoflagellate cysts through the sediment column, we can establish both the age of the sediment and what the environment and the oceanographic settings were like in the past.

~ Frida Snilstveit Hoem, palynologist

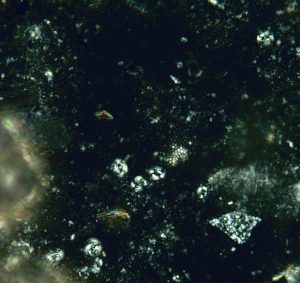

Forams & Nannofossils

[Credit: Anna Glüder]

Forams are found in oceans all around the world. Some look like pinecones, some like snail shells, and some like popcorn. Even though their shapes are so intricate, forams consist of only a single cell. They are not just beautiful but also really useful for reconstructing some properties of the past ocean: As they grow their shell, they draw their building material from the surrounding ocean water and, essentially, inscribe a record of ocean temperature and even global changes of ice-volume and sea-level. Since they are made of calcium carbonate, they even come with their own inbuilt clock: We can use 14C dating to know their age—if they lived during the past 40,000 years, that is. That they are made out of calcium carbonate unfortunately also means their shells don’t usually preserve very well on the cold and deep sea-floor of the Southern Ocean.

If you zoom in on the same image and flip on the polarizer, you can see even smaller microfossils: Nannofossils, in this case an algae type called Coccolithophores, are also made from calcium carbonate. They can be used for dating the older sediments but, just like forams, diatoms, and other fossils, they tell us something about previous conditions in the ocean. In the Southern Ocean cores, we barely found any though.

~ Anna Glüder.

(Anna is on the Sedimentology team but finds microfossils in the slides she uses to characterize the sediment.)

The descendants of these organisms (and sometimes the same species) live on Earth today, and they perform vital roles, from making oxygen to sequestering carbon dioxide to feeding the larger ocean animals. In fact, without them, life on Earth could not exist.

For me, they’re a reminder of how much of nature exists beyond a human’s immediate perception, exquisite creatures going about their business, minute worlds of beauty, which we would not know existed but for scientific endeavor and an adventurous spirit. It’s a feeling I have daily in the wild, remote Antarctic, whether gazing at penguins and whales, or peering at tiny fossils from long ago.