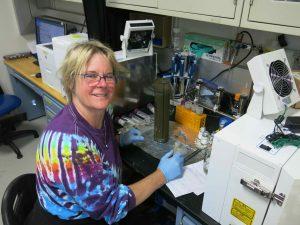

Ginny Edgcomb: Searching For The Fungi of Guaymas

This Q&A is part of the “Career Spotlight” series of Expedition 385

Can you tell me a little bit about you and your scientific background?

I’m Ginny Edgcomb and I’m from Woods Hole Oceanographic Institute, in the United States.

I studied finance and environmental science when I was an undergraduate at the University of Virginia. When I went back to grad school a few years after that, I studied biology and microbiology at the University of Delaware. I studied saltmarsh ecology, specifically, the sulfate-reducing bacteria.

Then, I went to Massachusetts and took a job as a postdoc on Cape Cod with the Marine Biological Laboratory where I studied the evolution of eukaryotes under Mitch Sogin; his lab studied protists, a complete switch, and one that I really loved.

The common denominator in my work has been low oxygen environments. It was during my postdoc time that I met Andreas Teske — he and I became friends and colleagues and I actually did a second postdoc with him studying hydrothermal vent microbes from Guaymas Basin, hyperthermophile bacteria and archaea.

So you have a history with Guaymas Basin.

Yeah! Around 1997, I started working on Guaymas samples when I went on a cruise to Guaymas with Andreas and Holger Jannasch, who was the scientist responsible for demonstrating the importance of chemoautotrophy at hydrothermal vents.

I’ve been in and out of Guaymas work for some time now, but always stay interested. It is a fascinating system.

How did you decide to become a scientist?

I love being outdoors. I love working on environmental issues and questions about how ecosystems work.

I love looking through the microscope at little things that I can’t see without the microscope. I wanted to study questions related to climate change. That was a topic that caught my interest. And I love the process of discovery, you know, traveling around different places and doing field sampling and discovering species that live in strange habitats.

I spent some time in Northeastern Australia sampling in the rainforest and studying protists there. The diversity, ecology and evolution of certain protist groups was really what I sunk my teeth into for quite a long time.

Then, more recently, I’ve started to realize that you can’t study protists in isolation when you are asking big questions about ecosystems and how they function. You have to look at the whole microbial community and how individuals and individual groups of organisms interact. There’s lots of interesting interactions between microbes in the environment; predator-prey relationships, symbioses including parasitism, and co-metabolism where microbes partner up to get the job done. So, my work now encompasses all three domains of life.

So, why is your research important and how do you think it changes your field?

I think that it helps to shed light on the role that different microbes play in the cycling of carbon and nutrients in oxygen-depleted environments. These are expanding worldwide. It’s important to understand how reduction in oxygen affects microbial communities that are at the base of the marine food chain.

It’s important to discover interactions, for instance, the symbiosis between protists and bacteria, or archaea — which have been unappreciated in terms of their abundance and possibly their contributions to cycling of nutrients and release of climate-active trace gases like methane.

What is your favorite thing about being a scientist?

My favorite thing about being a scientist is getting young people excited about science.

I interact quite a bit with high school students and younger undergraduate students and they get involved in projects in my laboratory. Some have been co-authors on peer-reviewed papers! Seeing them really get excited about what they do and then going off and pursuing research of their own, that really makes me feel good.

Within my own research, I think the thing that gets me the most excited is discovering something I haven’t seen before, you know, through the microscope. I love that.

What advice would you give to a teenager that is interested in science as a career?

I would encourage them get hands-on experience. Find a lab that they can volunteer in, whether it’s in industry or in a university or private research institution. Just get experience in different types of laboratories, and that will help you really find out what you love to do.

In your career, has there been something that really changed your view of how you look at things?

Yes! One is the abundance of symbioses that there are in the microbial world. So that is something that I have been wowed by numerous times when looking in different samples and seeing evidence of this.

There’s definitely intimate partnerships between microbes, and working out what they’re doing together is a lot of fun.

The other thing that’s surprising me is the role of fungi in the marine realm.

Microbial fungi were always kind of a pain to me in the lab, because they were contaminants of my samples continually. I would always take the data that had anything to do with fungi and I would just toss it out, until I started to realize that within the eukaryotes, the fungi are really resourceful, and organisms that can survive pretty well in almost every environment that we’ve looked for them. They’re not just contaminants!

So, among eukaryotes, rather than the protists, it’s the fungi that are dominating the subsurface biosphere, for instance, that we’re investigating now. It’s been a lot of fun to learn more about them.

Why did you decide to come on EXP385?

Because it was an opportunity to come back to Guaymas and to study the role of fungi in the degradation of hydrocarbons. That’s something that I always wanted to do, because we’ve found fungi in almost every subsurface sample that we’ve studied from a variety of IODP sites.

I want to know if they are as abundant in Guaymas Basin as they are in the other places. I’m also interested to know whether fungi cooperate with bacteria in the degradation of hydrocarbons.

You’ve sailed on the JR before. What’s the best and the toughest part of being on the JR?

Hmm…best things: besides having your laundry done all the time and your bed made, it’s just the interactions with the people, you know, the outreach folks and the scientists that sail. It’s an opportunity to meet really interesting people.

The toughest part is running out of fresh vegetables.

What do you do to relax onboard?

When I’m not on shift, I go to the gym. I take my heavy bag gloves and I hit the heavy bag, I ride the bike. I also like to read, and I go out on deck and watch the Mahi-mahi.

What essential goodies did you bring on board?

I brought a supply of chocolate, nuts and dried fruit. I also brought my own pillow and my slippers. I brought good headphones and my little Nespresso machine!

What hobbies do you have back home?

I love to ride my road bike. I like to listen to music. I like to hike, and kayak. I also do a lot of stuff in my garden.

Is there anything else you would like to tell me?

The one thing that I really like about the JR is the outreach stuff. I think it’s really cool to see the kids in your Zoom sessions get excited to talk to you.

Thanks!