Knock Knock Knockin’ on Basement Door

Drilling sets my teeth on edge.

It conjures hours spent with dentists, orthodontists, and memorably, an endodontist who root canaled the wrong tooth.

It’s not just the sound. I once wielded a power tool, 30 years ago. Not long after installing shelves in my home office closet, I noticed curious dark spots widening around the dozen holes that I had drilled with vigorous precision. “You hit the main drainpipe line of the house,” my husband observed, confirming that I had struck water a dozen times.

He’s a patient man, a mechanical engineer. He’d love the drill floor of the JR. I do too, despite my fraught history.

It’s a carnival of sound and color; a spectacle both shiny and grimy. There are roughnecks and even a barker of sorts: a driller who distinctly rolls his “r” when he calls out, “Core on deck!” Once in a while, someone is suspended in midair, inspecting the derrick’s upper reaches.

Crowded with heavy equipment and moving machinery, it’s hazardous terrain for interlopers. Lots of guys working on the JR drill floor have been here for decades. They have vast knowledge. And they have the feeling, too, which informs them as much as anything about what to do when.

“The scientists tell us what they want—sometimes top layers of the sea floor, other times rocks from deeper down—and we work out the most efficient and safest way to get if for them,” says tool pusher Glenn Barrett. After seven years on the JR, he still considers himself a new guy.

“Can I step there?” I ask.

I want to know if it’s ok for me to get a close-up peek at the hole. It looks like drill pipe is moving up and down through it, but that’s an illusion, Glenn explains. The pipe is stationary. It’s the ship that’s riding the Southern Ocean’s swells.

I inch closer, fixated on the hole. It goes clear down through the bottom of the JR. The fact that we don’t sink confounded me and at least one alert first-grader who broached the subject during a ship-to-shore virtual tour, prompting a quick lesson in equilibrium.

More properly referred to as the moonpool, the opening in the center of our ship allows ready access to the water and seafloor below. It’s among the JR’s more discreet marvels, situated as it is under a tower that rises 60 meters above waterline. In exchange for making us top-heavy, the derrick supports a million pounds of weight. This is key to our 24-7 operation of sending up to 6,500 meters of drill string through a series of connected iron pipes, down to the ocean floor, in water depths up to 6,000 meters.

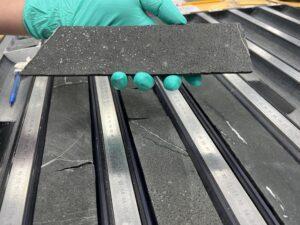

At the end of that apparatus today is a massive drill bit that’s rotary coring into basalt located more than 400 meters below sea floor. The thinking is that perhaps we have hit the elusive basement of the Agulhas Plateau.

These past weeks were a lesson in patience for the igneous petrologists. They’ve suffered through long days and nights of sediment recovery, including lots of enigmatic green stuff, a gift that looks nothing like what anybody wanted.

Their anticipation was keen enough to prompt Joerg Geldmacher to write two haiku:

Waiting for basement.

If it does not show up soon

I will go balloon.

——

Still no basement reached

Just the old green stuff again

Why am I here then?

Exacerbating his pain is the fact that the penetration rate now is much slower than it was with piston core drilling through softer stuff: a tedious one-meter-per-hour, compared with 10 times that rate in sediment.

The last core took six-plus hours to drill—more than half the night shift.

No matter.

If being on a ship full of people who speak in geological timescales teaches you anything, it’s that all good things take millennia.

“We’re getting remarkably long sections of recovery,” Peter Davidson enthuses. “It’s fresh!”

Fresh, as in unaltered, he clarifies, in case you were wondering how millions-of-years-old black basalt can be declared fresh.

The bottom line: Expedition 392 is reveling in rock.

Wonderfully evocative description of the drilling! I really felt like I was there.